Working Paper Number 107 January 2007 (updated May 2009)

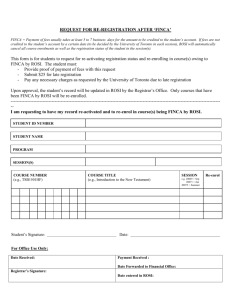

advertisement