A comparative study of additional qualifications at the interface of... and continuing education: findings from the United Kingdom

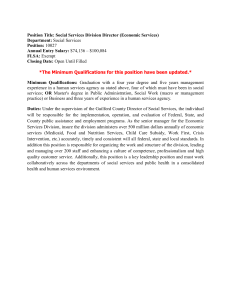

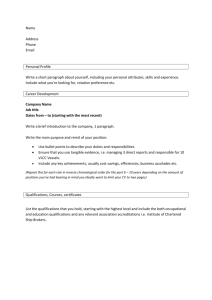

advertisement