Abusive Supervision and Workplace Deviance and the Moderating Effects

advertisement

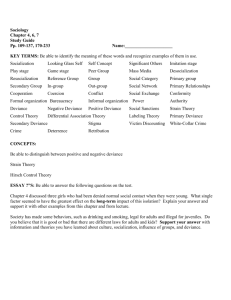

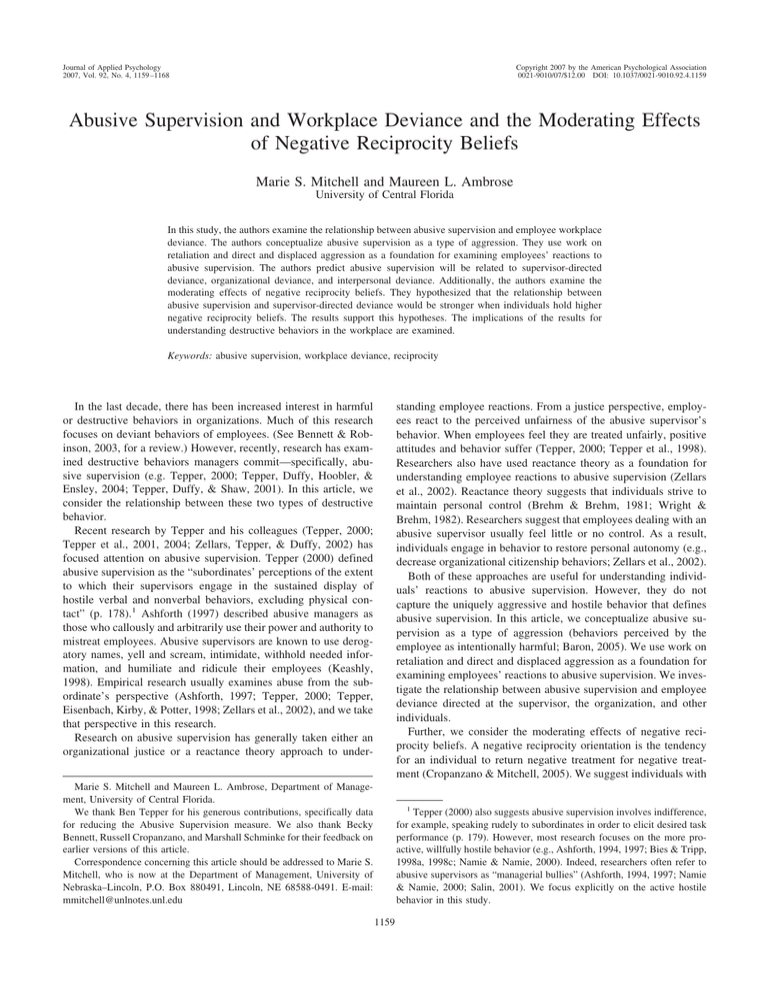

Journal of Applied Psychology 2007, Vol. 92, No. 4, 1159 –1168 Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association 0021-9010/07/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159 Abusive Supervision and Workplace Deviance and the Moderating Effects of Negative Reciprocity Beliefs Marie S. Mitchell and Maureen L. Ambrose University of Central Florida In this study, the authors examine the relationship between abusive supervision and employee workplace deviance. The authors conceptualize abusive supervision as a type of aggression. They use work on retaliation and direct and displaced aggression as a foundation for examining employees’ reactions to abusive supervision. The authors predict abusive supervision will be related to supervisor-directed deviance, organizational deviance, and interpersonal deviance. Additionally, the authors examine the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. They hypothesized that the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance would be stronger when individuals hold higher negative reciprocity beliefs. The results support this hypotheses. The implications of the results for understanding destructive behaviors in the workplace are examined. Keywords: abusive supervision, workplace deviance, reciprocity standing employee reactions. From a justice perspective, employees react to the perceived unfairness of the abusive supervisor’s behavior. When employees feel they are treated unfairly, positive attitudes and behavior suffer (Tepper, 2000; Tepper et al., 1998). Researchers also have used reactance theory as a foundation for understanding employee reactions to abusive supervision (Zellars et al., 2002). Reactance theory suggests that individuals strive to maintain personal control (Brehm & Brehm, 1981; Wright & Brehm, 1982). Researchers suggest that employees dealing with an abusive supervisor usually feel little or no control. As a result, individuals engage in behavior to restore personal autonomy (e.g., decrease organizational citizenship behaviors; Zellars et al., 2002). Both of these approaches are useful for understanding individuals’ reactions to abusive supervision. However, they do not capture the uniquely aggressive and hostile behavior that defines abusive supervision. In this article, we conceptualize abusive supervision as a type of aggression (behaviors perceived by the employee as intentionally harmful; Baron, 2005). We use work on retaliation and direct and displaced aggression as a foundation for examining employees’ reactions to abusive supervision. We investigate the relationship between abusive supervision and employee deviance directed at the supervisor, the organization, and other individuals. Further, we consider the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. A negative reciprocity orientation is the tendency for an individual to return negative treatment for negative treatment (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). We suggest individuals with In the last decade, there has been increased interest in harmful or destructive behaviors in organizations. Much of this research focuses on deviant behaviors of employees. (See Bennett & Robinson, 2003, for a review.) However, recently, research has examined destructive behaviors managers commit—specifically, abusive supervision (e.g. Tepper, 2000; Tepper, Duffy, Hoobler, & Ensley, 2004; Tepper, Duffy, & Shaw, 2001). In this article, we consider the relationship between these two types of destructive behavior. Recent research by Tepper and his colleagues (Tepper, 2000; Tepper et al., 2001, 2004; Zellars, Tepper, & Duffy, 2002) has focused attention on abusive supervision. Tepper (2000) defined abusive supervision as the “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which their supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (p. 178).1 Ashforth (1997) described abusive managers as those who callously and arbitrarily use their power and authority to mistreat employees. Abusive supervisors are known to use derogatory names, yell and scream, intimidate, withhold needed information, and humiliate and ridicule their employees (Keashly, 1998). Empirical research usually examines abuse from the subordinate’s perspective (Ashforth, 1997; Tepper, 2000; Tepper, Eisenbach, Kirby, & Potter, 1998; Zellars et al., 2002), and we take that perspective in this research. Research on abusive supervision has generally taken either an organizational justice or a reactance theory approach to underMarie S. Mitchell and Maureen L. Ambrose, Department of Management, University of Central Florida. We thank Ben Tepper for his generous contributions, specifically data for reducing the Abusive Supervision measure. We also thank Becky Bennett, Russell Cropanzano, and Marshall Schminke for their feedback on earlier versions of this article. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Marie S. Mitchell, who is now at the Department of Management, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, P.O. Box 880491, Lincoln, NE 68588-0491. E-mail: mmitchell@unlnotes.unl.edu 1 Tepper (2000) also suggests abusive supervision involves indifference, for example, speaking rudely to subordinates in order to elicit desired task performance (p. 179). However, most research focuses on the more proactive, willfully hostile behavior (e.g., Ashforth, 1994, 1997; Bies & Tripp, 1998a, 1998c; Namie & Namie, 2000). Indeed, researchers often refer to abusive supervisors as “managerial bullies” (Ashforth, 1994, 1997; Namie & Namie, 2000; Salin, 2001). We focus explicitly on the active hostile behavior in this study. 1159 RESEARCH REPORTS 1160 stronger negative reciprocity beliefs are more likely to direct deviant behavior toward the perceived source of harm. Thus, in the case of abusive supervision, stronger negative reciprocity beliefs should be associated with increased deviant behavior directed at the supervisor. In the following sections, we review relevant literature on abusive supervision, employee deviance, and negative reciprocity beliefs. Abusive Supervision Although abusive supervision is a low base-rate phenomenon, it has notable effects on employee attitudes (Tepper, 2000). Research shows that abusive supervision is related to lower levels of satisfaction, commitment, and justice perceptions, and higher levels of turnover, role conflict, and psychological distress (Ashforth, 1997; Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, 2002; Tepper, 2000). Fewer research studies have investigated the effects of abusive supervision on employee behaviors. Two studies by Tepper and colleagues (Tepper et al., 2004; Zellars et al., 2002) suggested that abusive supervision negatively affects organizational citizenship behaviors. Employees subjected to an abusive supervisor engage in fewer organizational citizenship behaviors (Zellars et al., 2002). Further, abusive supervision also negatively affects how employees perceive the genuineness of their peers’ organizational citizenship behaviors (Tepper et al., 2004). In addition to decreased positive behavior, we suggest abusive supervision will increase negative behavior, specifically, employee workplace deviance. In considering the relationship between abusive supervision and employee deviance, we found research on aggression and retaliation to be useful. This research suggests that interpersonal mistreatment (like abusive supervision) promotes retaliation and aggression displaced on other targets. For example, in their study on injustice and retaliation, Skarlicki and Folger (1997) found that conditions of multiple unfairness (distributive, procedural, and interactional) were associated with higher levels of organizational retaliatory behavior. Notably, these behaviors are characterized by both direct and displaced methods of retaliation (e.g., disobeyed supervisor’s instructions, left a mess unnecessarily, spread rumors about coworkers). We suggest employees engage in deviant behavior to retaliate directly against their abusive supervisor, and they may also engage in displaced deviant behavior. Moreover, we expect negative reciprocity beliefs to affect the relationship between abusive supervision and deviance. Workplace Deviance Workplace deviance is purposeful behavior that violates organizational norms and is intended to harm the organization, its employees, or both (Bennett & Robinson, 2003). Robinson and Bennett (1995) developed a widely accepted typology of workplace deviance, which categorizes two basic types of deviance: organizational and interpersonal. Organizational deviance is deviance directed toward the organization (e.g., shirking hours, purposefully extending overtime), and interpersonal deviance is deviance directed toward individuals (e.g., verbal abuse, sexual harassment). Recent research suggests it is useful to distinguish between two types of interpersonal deviance: deviant behaviors targeted against supervisors and those targeted at other individuals (Hershcovis et al., 2007). Thus, we investigate supervisor-directed deviance and (nonsupervisory) interpersonal deviance as well as organizational deviance when considering employee reactions to abusive supervision. Abusive Supervision and Employee Deviance Interpersonal treatment is a driving factor in deviant behavior (Robinson & Greenberg, 1998). Workplace experiences such as frustration, injustices, and threats to self are primary antecedents to employee deviance (Bennett & Robinson, 2003). Ashforth (1997) suggested that abusive supervision promotes feelings of frustration, helplessness, and alienation. Tepper (2000) found that abusive supervision negatively influences perceptions of justice. Thus, abusive supervision is a likely antecedent of employee deviance. As we noted above, we expect abusive supervision will be related to employee workplace deviance in two ways. First, employees may respond by directly retaliating against their supervisor. Second, employees may engage in “displaced” deviance by targeting the organization or other individuals. We discuss each of these below. Supervisor-Directed Deviance Retaliation plays an important role in research on aggression as well as research on workplace deviance. Retaliation involves the desire to punish an offender for unwarranted and malicious acts (Averill, 1982). Retaliation refers to behavior that seeks to “make the wrongdoer pay” for a transgression or event that harms or jeopardizes the victim in some meaningful way (Skarlicki & Folger, 2004, p. 374).2 Research on aggression demonstrates individuals may respond to the aggressive behavior of others by choosing to retaliate. For example, Brown (1968) found severe offensive behavior (social humiliation) resulted in strong retaliatory reactions, even at a personal cost to the retaliator. Bies and Tripp (1996) found that individuals seek revenge against those who harm them. A recent meta-analysis demonstrates that when individuals attribute responsibility to a harmdoer, they respond with anger and retaliation (Rudolph, Roesch, Greitemeyer, & Weiner, 2004). Several researchers have focused on investigating antecedents of retaliation in organizations (e.g., Allred, 1999; Bies & Tripp, 1998b; Bies, Tripp, & Kramer, 1997; Folger & Baron, 1996; Skarlicki & Folger, 1997, 2004). Empirical evidence demonstrates that individuals retaliate against perceived injustices (Greenberg & Alge, 1998; Skarlicki & Folger, 1997; Skarlicki, Folger, & Tesluk, 1999), threats to identity (Aquino & Douglas, 2003), violations of trust (Bies & Tripp, 1996), and personal offense (Aquino, Tripp, & Bies, 2001). When individuals feel they have been mistreated, retaliation is a deliberate, rational response (Bies & Tripp, 1996). 2 Our use of the term retaliation stems from the aggression literature. In organizational research, scholars have also used the term revenge to describe behavior that is intended to punish another for an offense (see, for example, Bies & Tripp, 1996, 1998a, 1998b, 1998c). Additionally, the term retaliation has been used in equal employment opportunity law and the whistle-blowing literature, in which retaliation is explicated as behavior that seeks to punish an employee who engages in protected behavior (Crockett & Gilmere, 1999). This use describes a specific instance of retaliatory behavior. RESEARCH REPORTS Interpersonal mistreatment is a central component of abusive supervision, and research indicates employees perceive supervisors as a dominant source of interpersonal mistreatment (Bies, 1999). Supervisors are reported to be the most prominent source of bullying at work (Neuman & Keashly, 2003). Indeed, both theoretical and empirical research suggests abusive supervision is related to retaliation. For example, Folger (1993) proposed that supervisors who fail to meet an acceptable standard of demeanor promote retaliation. Bies and Tripp (1998b) found that victims of abusive bosses directly undermined their bosses in private as well as openly ridiculed or challenged them. Baron and Neuman (1998) reported 31.4% of their respondents displayed aggression against a supervisor and felt justified doing so. Aquino, Tripp, and Bies (2006) demonstrated that lower level individuals are more likely to seek revenge than higher level individuals. Jones (2003) found that interactional injustice from an authority was significantly related to supervisor-directed retaliation. Further, a recent meta-analysis by Hershcovis et al. (2007) found that unfair supervisor treatment was a strong predictor of supervisor-targeted aggression. In the workplace deviance literature, retaliation is conceptualized as an interpersonal form of deviance (Bennett & Robinson, 2003). By definition, retaliation involves deliberate actions against a perceived harmdoer. In the case of abusive supervision, these behaviors would be targeted against the supervisor (i.e., supervisor-directed deviance). Therefore, we believe abusive supervision will be associated with supervisor-directed deviance. Hypothesis 1a: Abusive supervision will be positively related to supervisor-directed deviance. Displaced Deviance We also expect that abusive supervision will be related to other types of deviance. That is, in addition to targeting the source of the abuse, employees will react toward other targets. They will engage in deviance directed toward the organization (organizational deviance) or individuals other than the supervisor (interpersonal deviance). The theory of displaced aggression guides our thinking here (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939) Research on displaced aggression suggests that individuals who become angry and frustrated by a harmdoer may displace their aggression on individuals who are not the source of the harm (Dollard et al., 1939). Dollard et al. (1939) offered two reasons why individuals displace aggression. First, the harmdoer may not be available to retaliate against. Second, the victim may fear further retaliation from the harmdoer. Should either of these constraints occur, direct retaliation is curbed (Baron, 1971) and aggressive behaviors may be redirected or displaced on less powerful or more available targets (e.g., coworkers; Miller, 1941). Thus, retaliation is only one behavior employees may choose to engage in as a consequence of perceived abuse; victims may also displace their hostilities on others. We suggest that individuals subjected to abusive supervision may displace aggression toward the organization (i.e., organizational deviance)3 and individuals other than the supervisor (i.e., interpersonal deviance). Hypothesis 1b: Abusive supervision will be positively related to organizational deviance. 1161 Hypothesis 1c: Abusive supervision will be positively related to (nonsupervisory) interpersonal deviance. Moderating Effects of Negative Reciprocity Beliefs Retaliation plays an important role in our conceptualization of the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisordirected deviance. The principle of retaliation emphasizes the biblical injunction of “a life for a life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth . . . bruise for bruise” (Exodus 21:23–25) and is a common theme in deviance research (cf. Bennett & Robinson, 2003). Gouldner (1960) captured this principle in his negative norm of reciprocity. Reciprocity encompasses quid pro quo behaviors, meaning that something given generates an obligation to return an equivalent gesture. Most research focuses on positive reciprocity, which promotes stability in relationships through considerate, valued, and balanced exchanges. Favorable treatment generates favorable treatment. However, Gouldner (1960) also noted that individuals may endorse a negative norm of reciprocity, under which unfavorable treatment promotes “not the return of benefits but the return of injuries” (p. 172). Indeed, individuals may be guided by negative reciprocity beliefs whereby they believe that when someone mistreats them, it is acceptable to retaliate in return (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Yet, Gouldner suggested that not all victims seek to retaliate. Some may feel it is acceptable to “turn the other cheek.” Thus, individuals vary in their beliefs about the appropriateness of negative reciprocity. Individuals who endorse negative reciprocity believe retribution is the correct and proper response to unfavorable treatment (Eisenberger, Lynch, & Aselage, 2004). Those who hold strong negative reciprocity beliefs are more likely to seek retaliation than avoidance (McLean Parks, 1998). Those who do not hold strong negative reciprocity beliefs are less likely to engage in retaliatory behavior. Indeed, research demonstrates that individuals vary in their beliefs about the appropriateness of negative reciprocity. Moreover, individuals’ negative reciprocity beliefs influence behavioral choices (Gallucci & Perugini, 2003; Perugini, Gallucci, Presaghi, & Ercolani, 2003). In sum, individuals with strong negative reciprocity beliefs consider retaliation an appropriate response to negative treatment. We suggest negative reciprocity beliefs will moderate the relationship between abusive supervision and employee deviance. However, because negative reciprocity is a quid pro quo belief, the focus of retaliation should be the source of the mistreatment (the abusive supervisor). Thus, we suggest that for individuals with stronger negative reciprocity beliefs, the relationship between perceived abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance will be stronger than for those who do not endorse negative reciprocity. However, we do not expect negative reciprocity beliefs to affect the relationship between abusive supervision and deviance toward the organization or toward individuals other than the supervisor. 3 Some researchers suggest that individuals may target the organization in an effort to retaliate against a supervisor (Ambrose, Seabright, & Schminke, 2002). In our conceptualization, this is still displaced aggression, because the retaliatory attempt is indirect rather than direct. The target of the aggression differs from the source of the harm. RESEARCH REPORTS 1162 Hypothesis 2: Negative reciprocity beliefs will moderate the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisordirected deviance but will not moderate the relationship between abusive supervision and other forms of deviance (organizational or interpersonal). Abusive supervision will be more strongly related to supervisor-directed deviance when individuals more strongly believe in negative reciprocity. Method Sample and Procedure Surveys were distributed to individuals called for jury duty by a county circuit court in the Southeastern United States. The researchers addressed potential jurors at the beginning of the day as they waited to learn if they would be required to serve. We explained that the survey had nothing to do with the jury or court system, but rather, that we sought to understand more about sensitive issues that affect individuals at work. Therefore, we indicated that willing participants had to be currently employed. Interested participants picked up surveys from and returned surveys to the researcher. Over the course of 8 weeks, 427 individuals agreed to participate in the study (30.5% response rate). The average age of the participants was 42.7 years old (SD ⫽ 11.95); average company tenure was 8.7 years (SD ⫽ 8.15), and tenure with a supervisor was 3.7 years (SD ⫽ 4.08); 38.3% were currently working in supervisory positions; and 56.9% of the sample was female. Measures Abusive supervision. We used a shortened 5-item version of Tepper’s (2000) Abusive Supervision measure. To develop this shortened measure, we performed exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on two separate data sets that used the original 15-item measure (N ⫽ 741 from Tepper, 2000, and N ⫽ 338 from Tepper et al., 2004).4 (See Appendixes A and B for results.) The analyses revealed two distinct factors: One reflected active interpersonal abuse by the supervisor (e.g., “ridicules me” and “tells me my thoughts and feelings are stupid”). The other reflected more passive acts of abuse (e.g., “doesn’t give me credit for jobs requiring a lot of effort”). Because the active dimension is most consistent with our interest, we used the 5 items representing this factor as our indicator of abusive supervision. Respondents indicated their agreement with each item using a 7-point scale (1 ⫽ strongly agree, 7 ⫽ strongly disagree). Deviance. We assessed interpersonal and organizational deviance with measures developed by Bennett and Robinson (2000). The measures used a 7-point scale (1 ⫽ never, 7 ⫽ daily) and asked respondents to indicate the number of times in the last year that they had engaged in the behavior described. Twelve items assessed perceptions of organizational deviance. Respondents were asked to indicate behaviors targeted at the company for which they were currently working. Seven items assessed perceptions of interpersonal deviance. Respondents were asked to indicate behaviors targeted at coworkers. Further, we adapted language from the interpersonal deviance items from both the Bennett and Robinson (2000) and Aquino, Lewis, and Bradfield (1999) measures to generate a 10-item measure of supervisor-directed deviance, which asked respondents to indicate behaviors targeted against their current supervisor.5 These items are shown in Appendix C. Negative reciprocity beliefs. Negative reciprocity beliefs were assessed with a 14-item measure developed by Eisenberger et al. (2004). The measure contains statements concerning the advisability of retribution for unfavorable treatment. Respondents were asked to rate their agreement on a 7-point scale (1 ⫽ strongly agree, 7 ⫽ strongly disagree). Controls. Past research suggests that trait anger influences deviant reactions (Eisenberger et al., 2004; Fox & Spector, 1999). Therefore, we controlled for trait anger in our analyses. We used the anger subscale of Buss and Perry’s (1992) Aggression Questionnaire, which assesses the dispositional tendency toward anger in everyday life. Participants expressed agreement on a 5-point scale (1 ⫽ very slightly true of me, 5 ⫽ very highly true of me). We controlled for age, because research also suggests that age is related to deviant reactions (Aquino & Douglas, 2003; Grasmick & Kobayashi, 2002). Last, we controlled for employees’ tenure with the supervisor, because research suggests that tenure with the supervisor influences reactions (Bauer & Green, 1996; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). Social desirability check. In order to assess for socially desirable responses in the deviance, abusive supervision, negative reciprocity beliefs, and trait anger measures, we examined the correlation between individual self-reported items to those of social desirability. We assessed social desirability with an 18-item short version of the Paulhus (1991) measure, which has been used in previous research investigating workplace deviance (Tripp, Bies, & Aquino, 2002). Consistent with previous research (Aquino et al., 1999), we eliminated items that correlated greater than .30 with the Paulhus items. Thus, four negative reciprocity items were eliminated from the original set: “If a person wants to be your enemy, you should 4 We thank Ben Tepper for sharing his data with us for these analyses. Although research suggests distinguishing between deviant behaviors targeted against supervisors and those targeted at other individuals (Hershcovis et al., 2007), the interpersonal deviance measures had not been adapted in this way previously. To ensure that these three measures of deviance were distinct, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses. First, we examined a three-factor model that included the three separate deviance measures (interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and supervisor-directed deviance). This model provided an acceptable fit to the data, 2(374) ⫽ 1,689.05, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .09, CFI ⫽ .90, NFI ⫽ .88. We compared the three-factor model to (a) a two-factor model that combined supervisor-directed deviance and interpersonal deviance into a single interpersonal factor, 2(376) ⫽ 2,094.32, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .10, CFI ⫽ .88; NFI ⫽ .85, (b) a two-factor model that combined interpersonal deviance and organizational deviance into a single displaced deviance factor, 2(376) ⫽ 2,301.37, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .11, CFI ⫽ .88, NFI ⫽ .85, and (c) a single-factor model that combined all deviance items into one deviance factor, 2(377) ⫽ 2,522.09, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .12, CFI ⫽ .86, NFI ⫽ .84. The results of our analysis revealed the three-factor model produced a significant improvement in chi-squares over the two-factor interpersonal deviance model, ⌬2(2) ⫽ 405.27, p ⬍ .001; the two-factor displaced deviance model, ⌬2(2) ⫽ 612.32, p ⬍ .001; and the one-factor model, ⌬2(3) ⫽ 833.04, p ⬍ .001, suggesting the three-factor model provided a better fit than the alternative models (Schumacker & Lomax, 1996). 5 RESEARCH REPORTS treat them like an enemy” (r ⫽ .37), “If someone treats you badly, you should treat that person badly in return” (r ⫽ .36), “When someone hurts you, you should find a way they won’t know about to get even” (r ⫽ .37), and “If someone treats me badly, I feel I should treat them even worse” (r ⫽ .39). The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the negative reciprocity beliefs measure without these four items was .86. All other items showed low correlations with social desirability (i.e., r ⬍ .30) and were retained in our analyses. Results Measurement Model Results We conducted confirmatory factor analyses with maximum likelihood estimation to examine the distinctness of the variables. The measurement model consisted of five factors: abusive supervision, negative reciprocity beliefs, interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and supervisor-directed deviance items. The results indicated that the five-factor model provided a good fit to the data, 2(1209) ⫽ 3,163.63, p ⬍ .001, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) ⫽ .06, comparative fit index (CFI) ⫽ .93, normed fit index (NFI) ⫽ .93. RMSEA scores below .08 (Hoyle & Panter, 1995) and CFI and NFI scores above .90 (Bentler & Bonnett, 1990; Bollen, 1989) indicate that the indices fall above the guidelines for a good fit. We compared the five-factor model to (a) a four-factor model (where organizational and interpersonal deviance items were combined into a single “displaced deviance” factor), 2(1214) ⫽ 3,916.08, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .08, CFI ⫽ .91, NFI ⫽ .92, (b) a three-factor model (where all deviance items were combined into a single factor), 2(1218) ⫽ 4,219.28, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .08, CFI ⫽ .90, NFI ⫽ .88, and (c) a single-factor model, 2(1224) ⫽ 10,899, p ⬍ .001, RMSEA ⫽ .14, CFI ⫽ .39, NFI ⫽ .78. The five-factor model produced a significant improvement in chi-squares over the four-factor model, ⌬2(5) ⫽ 752.45, p ⬍ .001; the three-factor model, ⌬2(9) ⫽ 1,055.65, p ⬍ .001; and the one-factor model, ⌬2(15) ⫽ 7,735.91, p ⬍ .001, suggesting a better fit than the other models (Schumacker & Lomax, 1996). Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and reliabilities for the study variables. Results of Tests of the Hypotheses We used hierarchical regression to assess the hypotheses. Following the recommendation of Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003), we mean centered the predictor variables to reduce multicollinearity. Variance inflation factor scores were assessed for predictive variables, all of which were well below the 10.0 standard (Ryan, 1997). This indicates that multicollinearity did not present a biasing problem. It is worth noting the low means for the abusive supervision and the deviance measures. These means are consistent with those in other studies (cf. Aquino et al., 1999; Bennett & Robinson, 2000; Tepper, 2000; Tepper et al., 2001, 2004). Indeed, abusive supervision and workplace deviance are low base-rate phenomena (Bennett & Robinson, 2000 and Tepper, 2000). Nevertheless, the means 1163 suggest the data are not normally distributed. Although ordinary least squares is robust to nonnormality (Mertler & Vannatta, 2002), we conducted a transformation for negatively skewed data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996) and also analyzed the transformed data. The results of these analyses are consistent with the results presented below. Regression results are provided in Table 2. Hypothesis 1 proposes that abusive supervision will be positively related to (a) supervisor-directed deviance, (b) organizational deviance, and (c) interpersonal deviance. The results support this hypothesis. Abusive supervision is positively and significantly related to each type of deviance. Further, trait anger was significantly and positively related to supervisor-directed deviance and interpersonal deviance. Additionally, negative reciprocity beliefs were significantly and positively related to all types of deviance. Hypothesis 2 predicts that negative reciprocity beliefs will moderate the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisordirected deviance, but not the relationship between abusive supervision and other types of deviance. The results show that the Abusive Supervision ⫻ Negative Reciprocity interaction was significantly and positively related to only supervisor-directed deviance. The results support Hypothesis 2. Figure 1 shows the negative reciprocity beliefs and abusive supervision interaction on supervisor-directed deviance. Values representing plus or minus one standard deviation from the mean were used to generate the plotted regression lines (Cohen et al., 2003). As predicted, the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance was stronger when individuals had higher negative reciprocity beliefs. Discussion Previous research demonstrates abusive supervision negatively affects employee attitudes and employees’ willingness to engage in positive behavior (Tepper et al., 2004; Zellars et al., 2002). The results of this study show abusive supervision influences employees’ willingness to engage in negative behavior as well. Specifically, abusive supervision is positively related to all types of employee deviance. Moreover, the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance is stronger for employees with stronger negative reciprocity beliefs. Below we discuss these findings in more detail and the implications for managers and organizations. Research on workplace deviance suggests that individuals may direct their behaviors at individuals or at the organization. We predicted abusive supervision would be related to both direct retaliation—supervisor-directed deviance—as well as displaced deviant behaviors— deviance targeted at other individuals (coworkers) and at the organization. Our results support this prediction. Abusive supervisory behavior is associated not only with harm to the source of the abuse but also “collateral” damage to the organization and others in the workplace. In addition to the main effect of abusive supervision on employee deviance behaviors, we also expected negative reciprocity beliefs would play a role in the relationship. As predicted, the results show that negative reciprocity beliefs strengthened the relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance. Employees with stronger negative reciprocity beliefs who believed their supervisor was abusive engaged in more RESEARCH REPORTS 1164 Table 1 Summary Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Abusive supervision Negative reciprocity Supervisor-directed deviance Organizational deviance Interpersonal deviance Trait anger Age Tenure with supervisor M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1.82 2.35 1.51 1.66 1.76 2.41 42.72 3.70 1.30 1.03 0.69 0.67 0.88 0.69 11.95 4.08 (.89) .18 .40 .17 .21 .10 .07 ⫺.02 (.86) .24 .31 .30 .34 ⫺.14 ⫺.02 (.82) .53 .64 .28 ⫺.16 .03 (.79) .58 .14 ⫺.28 ⫺.05 (.82) .32 ⫺.17 .04 (.92) .10 ⫺.01 — .29 — Note. Internal reliability coefficients (alphas) appear in parentheses along the main diagonal. Correlations greater than .14 are significant at p ⬍ .01 and those greater than .10, at p ⬍ .05, two-tailed. supervisor-directed deviance than individuals who did not endorse negative reciprocity. The results also show that negative reciprocity beliefs did not significantly influence the relationship between abusive supervision and other types of deviant behavior (neither organizational nor interpersonal deviance). Thus, as expected, negative reciprocity is significantly related only to the quid pro quo behaviors targeted against the abuser. Our results also reveal some unexpected findings. First, there was a significant main effect for negative reciprocity beliefs on all types of deviance. Whereas the interaction findings support the belief that negative reciprocity promotes retribution, the main effect indicates that individuals who hold strong negative reciprocity beliefs also reported greater levels of all types of deviance. This finding is consistent with Eisenberger et al. (2004), who have argued that individuals with strong negative reciprocity beliefs hold a catharsis approach to aggression and get satisfaction from aggressing against any target, whether guilty or innocent. Thus, negative reciprocity beliefs may also indicate a general propensity toward workplace deviance. The findings on trait anger are also interesting. Trait anger was positively related to supervisor-directed and interpersonal deviance, but not organizational deviance. Anger has been linked to theories of frustration-aggression (Dollard et al., 1939) and deviance. (See Perrowe & Spector, 2002 for a review.) The results of this study suggest that trait anger is differentially related to different types of deviance. These results are consistent with Douglas and Martinko (2001), who have argued that high trait-anger individuals believe others purposefully and unnecessarily caused them harm. They found that individuals with high trait-anger were more inclined to feel vengeful and make hostile attributions about other persons. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis on workplace aggression found that trait anger was more strongly related to interpersonal than organizational forms of aggression (Hershcovis et al., 2007). Similarly, we found that trait anger is related only to deviance directed at individuals. Thus, it seems that interpersonal interaction and how it is interpreted by individuals with high trait anger is important to understanding trait anger and behavior. The results of this study have important implications for researchers and managers. Most notable, the results suggest that abusive supervision is positively associated with workplace deviance. Below, we consider two ways in which abusive supervision might affect the overall level of workplace deviance. First, abusive supervision is associated with higher levels of deviance directed at others. In our study, we explicitly examined Table 2 Multiple Regressions of Hypothesized Relationships Supervisor-directed deviance Variable Control Trait anger Age Tenure with supervisor Predictor Abusive supervision Negative reciprocity Moderator Abusive Supervision ⫻ Negative Reciprocity ⌬ R2 2 R Adjusted R2 F Organizational deviance Interpersonal deviance Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 .26*** ⫺.15*** .08 .18*** ⫺.17*** .09* .18*** ⫺.16*** .09** .11** ⫺.27*** .03 .00 ⫺.25*** .03 ⫺.01 ⫺.24*** .04 .30*** ⫺.16*** .09 .22*** ⫺.15*** .10** .22*** ⫺.15*** .10** .39*** .11** .37*** .10** .15*** .28*** .14*** .27*** .16*** .18*** .15*** .18*** .17*** .26 .25 27.31*** .08* .01* .27 .26 23.40*** .10*** .18 .17 17.06*** .05 .00 .19 .17 14.26*** .06*** .19 .18 17.60*** .07 .01 .19 .18 15.12*** .09 .09 13.47*** .08 .08 11.73*** Note. Standardized beta coefficients are reported. Statistical tests are based on one-tailed tests. * p ⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001. .12 .12 18.02*** RESEARCH REPORTS Figure 1. Interaction of abusive supervision and negative reciprocity on supervisor-directed deviance. Values represent standard deviation from the mean. interpersonal deviance directed at coworkers. Thus, abusive supervision may set off a chain of events in which employee deviance that results from abusive supervision is directed at coworkers, who in turn retaliate toward their abusive coworker, and so on, resulting in a spiral of deviance (an effect similar to Andersson & Pearson’s [1999] conceptualization of spiraling incivility). Second, social learning theory suggests that actions exhibited by agents of an organization (supervisors) establish models of behavior (Bandura, 1973). As such, supervisors may be “modeling” deviant behaviors (O’Leary-Kelly, Griffin, & Glew, 1996). O’Leary-Kelly et al. (1996) suggest that witnessing aggressive (or abusive) models reduces the observer’s inhibitions to act out similarly. Further, watching aggression may stimulate the observer’s emotional arousal, which also enhances aggressive tendencies (Berkowitz, 1993; O’Leary-Kelly et al., 1996). Thus, abusive supervision may create an atmosphere that increases the overall level of employee deviance. Of course, because our data are cross-sectional, inferences of causality cannot be made. Although our conceptualization of the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance is consistent with previous work in the area in which abusive supervision is the antecedent of employee behavior (e.g., Ashforth, 1997; Bamberger & Bacharach, 2006; Tepper, 2000; Tepper et al., 2001, 2004), other explanations for our findings may exist. For example, employee deviance may also elicit supervisor responses (e.g., reprimands, warnings) that are perceived as abusive. Additionally, a hostile work climate (or organizational norms for aggression and interpersonal disrespect) could encourage both abusive supervision and deviance.6 However, it is difficult to construct an argument for why belief in negative reciprocity would moderate the relationship between employee supervisor-directed deviance and abusive supervision but not the relationships between other types of deviance and abusive supervision in either of these situations. Nonetheless, given the limitations of data for causality testing, future research should examine the causal processes underlying the relationship between abusive supervision and employee deviance. There are other limitations that warrant note. All variables were assessed in a single survey. This raises concerns about common method variance. Although research indicates that common 1165 method variance may not pose a significant biasing problem (Spector, 1987), we conducted the Harmon’s single-factor test (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003, for a review). This analysis suggests that there is neither one single factor nor a dominant general factor that accounts for the majority of the variance in individual responses. Further, Podsakoff et al. recommend other nonstatistical methods for reducing common method variance. They recommend protecting respondents’ anonymity and ensuring that the survey contains questions for which there are no right or wrong answers. We followed both these suggestions. Nonetheless, future research might benefit from other methodological precautions, such as collecting data from different sources. Finally, the use of self-report measures is a limitation. Two issues arise here. First, as is common with research on aggression, we examined subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervision. The supervisor’s perspective was not assessed. This focus is consistent with previous research on aggression (Dollard et al., 1939) and retaliation (Skarlicki & Folger, 2004). The underlying belief is that aggression is in the eye of the beholder; if people perceive that someone is aggressing against them, they will respond to the perceived aggression. However, this approach does not assess the supervisor’s motive. Second, some researchers contend objective data should be integrated into deviance research (Greenberg & Folger, 1988; Robinson & Greenberg, 1998). However, objective data may suffer from criterion deficiency and contamination, because organizations only report these behaviors when employees are caught or reprimanded (Fox & Spector, 1999). Nonetheless, with selfreports, employees may underreport their deviant behaviors because they fear being caught and punished (Lee, 1993). Our venue (jury duty) lessens the fear of possible negative consequences from one’s employer. Additionally, we took methodological precautions by testing for social desirability. Still, there are limitations to self-report deviance data. Interest in destructive behavior in organizations has increased in the last 10 years. We contribute to this literature by examining the relationship between two types of destructive behaviors: abusive supervision and employee deviance. Our results suggest that deviance at one level of the organization (supervisors) is related to other forms of deviance. Workplace deviance is a costly problem for organizations (Robinson & Greenberg, 1998). Understanding the role abusive supervision plays in workplace deviance may help organizations and researchers identify ways to reduce both the financial and psychological costs of deviant behavior. This study is one step toward that end. 6 We thank an anonymous reviewer for these observations. References Allred, K. G. (1999). Anger and retaliation: Toward an understanding of impassioned conflict in organizations. In R. J. Lewicki, R. J. Bies, & B. H. Sheppard (Eds.), Research on negotiation in organizations (Vol. 7, pp. 27–58). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Ambrose, M. L., Seabright, M. A., & Schminke, M. (2002). Sabotage in the workplace: The role of organizational injustice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 947–965. 1166 RESEARCH REPORTS Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 24, 452– 471. Aquino, K., & Douglas, S. (2003). Identity threat and antisocial behavior in organizations: The moderating effects of individual differences, aggressive modeling, and hierarchical status. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90, 195–208. Aquino, K., Lewis, M. U., & Bradfield, M. (1999). Justice constructs, negative affectivity, and employee deviance: A proposed model and empirical test. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 1073–1091. Aquino, K., Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2001). How employees respond to personal offense: The effects of blame attribution, victim status, and offender status on revenge and reconciliation in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 52–59. Aquino, K., Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2006). Getting even or moving on? Power, procedural justice, and types of offense as predictors of revenge, forgiveness, reconciliation, and avoidance in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 653– 658. Ashforth, B. (1994). Petty tyranny in organizations. Human Relations, 47, 755–778. Ashforth, B. (1997). Petty tyranny in organizations: A preliminary examination of antecedents and consequences. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 14, 126 –140. Averill, J. R. (1982). Anger and aggression: An essay on emotion. New York: Springer-Verlag. Bamberger, P. A., & Bacharach, S. B. (2006). Abusive supervision and subordinate problem drinking: Taking resistance, stress and subordinate personality into account. Human Relations, 59, 723–752. Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. New York: Prentice Hall. Baron, R. A. (1971). Magnitude of victim’s pain cues and level of prior anger arousal as determinants of adult aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17, 236 –243. Baron, R. A. (2005). Workplace aggression and violence: Insights from basic research. In R. W. Griffin & A. M. O’Leary-Kelly (Eds.), The dark side of organizational behavior (pp. 23– 61). New York: Jossey-Bass. Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1998). Workplace aggression–The iceberg beneath the tip of workplace violence: Evidence on its forms, frequency, and targets. Public Administration Quarterly, 21, 446– 464. Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1996). The development of leader-member exchange: A longitudinal test. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1538 –1567. Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). The development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 349 –360. Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2003). The past, present, and future of workplace deviance research. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of science (2nd ed., pp. 247–281). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Bentler, P. M., & Bonnett, D. G. (1990). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588 – 606. Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. New York: McGraw-Hill. Bies, R. J. (1999). Interactional (in)justice: The sacred and the profane. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational behavior (pp. 89 –118). San Francisco: New Lexington Press. Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (1996). Beyond distrust: Getting even and the need for revenge. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 246 –260). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (1998a). The many faces of revenge: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In R. W. Griffin, A. O’Leary-Kelly, & J. Collins (Eds.), Dysfunctional behavior in organizations, Vol. 1: Violent behavior in organizations (pp. 49 – 68). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (1998b). Revenge in organizations: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In R. W. Griffin, A. O’Leary-Kelly, & J. M. Collins (Eds.), Dysfunctional behavior in organizations: Non-violent dysfunctional behavior (pp. 49 – 67). Stamford, CT: JAI Press. Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (1998c). Two faces of the powerless: Coping with tyranny in organizations. In R. M. Kramer & M. A. Neale (Eds.), Power and influence in organizations (pp. 203–220). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bies, R. J., Tripp, T. M., & Kramer, R. M. (1997). At the breaking point: Cognitive and social dynamics of revenge in organizations. In R. A. Giacalone & J. Greenberg (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in organizations (pp. 18 –36). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Brehm, J., & Brehm, S. (1981). Psychological resistance: A theory of freedom and control. New York: Academic Press. Brown, B. R. (1968). The effects of need to maintain face on interpersonal bargaining. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4, 107–122. Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452– 459. Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Crockett, R. W., & Gilmere, J. A. (1999). Retaliation: Agency theory and gaps in the law. Public Personnel Management, 28, 39 – 49. Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874 –900. Dollard, J., Doob, L. W., Miller, N. E., Mowrer, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Douglas, S. C., & Martinko, M. J. (2001). Exploring the role of individual differences in the predictions of workplace aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 547–559. Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., & Pagon, M. (2002). Social undermining and social support in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 331–351. Eisenberger, R., Lynch, P., & Aselage, J. (2004). Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(6), 787–799. Folger, R. (1993). Reactions to mistreatment at work. In J. K. Murnighan (Ed.), Social psychology in organizations (pp. 161–183). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Folger, R., & Baron, R. A. (1996). Violence and hostility at work: A model of reactions to perceived injustice. In G. R. VandenBos & E. Q. Bulato (Eds.), Violence on the job: Identifying risks and developing solutions (pp. 51– 85). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Fox, S., & Spector, P. E. (1999). A model of work frustration-Aggression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 915–931. Gallucci, M., & Perugini, M. (2003). Information seeking and reciprocity: A transformational analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 473– 495. Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178. Grasmick, H. R., & Kobayashi, E. (2002). Workplace deviance in Japan: Applying an extended model of deterrence. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23, 21– 43. Greenberg, J., & Alge, B. J. (1998). Aggressive reactions to workplace injustice. In R. W. Griffin, A. O’Leary-Kelly, & J. Collins (Eds.), Monographs in organizational behavior and industrial relations: Vol. 23. Dysfunctional behavior in organizations (pp. 83–117). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Greenberg, J., & Folger, R. (1988). Controversial issues in social research methods. New York: Springer-Verlag. Hershcovis, S. M., Turner, N., Barling, J., Arnold, K. A., Dupre, K. E., RESEARCH REPORTS Inness, M., et al. (2007). Predicting workplace aggression: A metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 228 –238. Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 158 –176). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Jones, D. A. (2003). Predicting retaliation in the workplace: The theory of planned behavior and organizational justice. In D. H. Nagao (Ed.), Best paper proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management [CD], L1– 6. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management. Keashly, L. (1998). Emotional abuse in the workplace: Conceptual and empirical issues. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 1, 85–117. Lee, R. M. (1993). Doing research on sensitive topics. London: Sage. McLean Parks, J. (1998). The fourth arm of justice: The art and science of revenge. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 6, 113–144. Mertler, C. A., & Vannatta, R. A. (2002). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Pyrczak. Miller, N. E. (1941). The frustration-aggression hypothesis. Psychological Review, 48, 337–342. Namie, G., & Namie, R. (2000). The bully at work. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks. Neuman, J. H., & Keashly, L. (2003, April). Workplace bullying: Persistent patterns of workplace aggression. In J. Greenberg, & M. E. Roberge (Chairs), Vital but neglected topics in workplace deviance research. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Orlando, FL. O’Leary-Kelly, A., Griffin, R., & Glew, D. (1996). Organization-motivated aggression: A research framework. Academy of Management Review, 21, 225–253. Paulhus, D. L. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In J. P. Robinson, P. Shaver, & L. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of psychology and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Perrowe, P. L., & Spector, P. E. (2002). Personality research in the organizational sciences. In K. M. Rowland, & G. R. Ferris (Eds.), Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management (Vol. 21, pp. 1– 63). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Perugini, M., Gallucci, M., Presaghi, F., & Ercolani, A. P. (2003). The personal norm of reciprocity. European Journal of Personality, 17, 251–283. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879 –903. Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–572. Robinson, S. L., & Greenberg, J. (1998). Employees behaving badly: Dimensions, determinants, and dilemmas in the study of workplace deviance. In C. L. Cooper & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), Trends in organizational behavior (Vol. 5, pp. 1–30). New York: Wiley. 1167 Rudolph, U., Roesch, S. C., Greitemeyer, T., & Weiner, B. (2004). A meta-analytic review of help giving and aggression from an attributional perspective: Contributions to a general theory of motivation. Cognition & Emotion, 18, 815– 848. Ryan, T. P. (1997). Modern regression methods. New York: Wiley. Salin, D. (2001). Prevalence and forms of bullying among business professionals: A comparison of two different strategies for measuring bullying. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 425– 441. Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (1996). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: The role of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 434 – 443. Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (2004). Broadening our understanding of organizational retaliatory behavior. In R. W. Griffin & A. M. O’LearyKelly (Eds.), The dark side of organizational behavior (pp. 373– 402). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Skarlicki, D. P., Folger, R., & Tesluk, P. (1999). Personality as a moderator in the relationship between fairness and retaliation. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 100 –108. Spector, P. E. (1987). Method variance as an artifact in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Myth or significant problem? Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 438 – 443. Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics (3rd ed.). New York: Harper Collins. Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178 –190. Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Hoobler, J., & Ensley, M. D. (2004). Moderators of the relationship between coworkers’ organizational citizenship behavior and fellow employees’ attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 455– 465. Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). Personality moderators of the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates’ resistance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 974 –983. Tepper, B. J., Eisenbach, R. J., Kirby, S. L., & Potter, P. W. (1998). Test of a justice-based model of subordinates’ resistance to downward influence attempts. Group & Organization Management, 23, 144 –160. Tripp, T. M., Bies, R. J., & Aquino, K. (2002). Poetic justice or petty jealousy? The aesthetics of revenge. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 966 –984. Wayne, S., Shore, L., & Liden, R. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 82–111. Wright, R., & Brehm, S. (1982). Reactance as impression management: A critical review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 608 – 618. Zellars, K. L., Tepper, B. J., & Duffy, M. K. (2002). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1068 –1076. (Appendixes follow) RESEARCH REPORTS 1168 Appendix A Exploratory Factor Analysis Factor Loadings for Tepper’s (2000) Abusive Supervision Measure Factor Item 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. a Ridicules me. Tells me my thoughts or feelings are stupid.a Gives me the silent treatment. Puts me down in front of others.a Invades my privacy. Reminds me of my past mistakes and failures. Doesn’t give me credit for jobs requiring a lot of effort. Blames me to save himself/herself embarrassment. Breaks promises he/she makes. Expresses anger at me when he/she is mad for another reason. Makes negative comments about me to others.a Is rude to me. Does not allow me to interact with my coworkers. Tells me I’m incompetent.a Lies to me. 1 2 .23 .28 .45 .30 .58 .46 .60 .63 .78 .53 .40 .54 .42 .16 .76 .71 .61 .49 .79 .29 .50 .29 .30 .17 .45 .68 .55 .29 .65 .23 Note. Dominant factor loadings are presented in boldface. Factor 1 ⫽ passive-aggressive abusive supervision; Factor 2 ⫽ active-aggressive abusive supervision. Factors accounted for 48.1% and 9.0% of the total variance, respectively (N ⫽ 741). Data are from “Consequences of Abusive Supervision,” by B. J. Tepper, 2000, Academy of Management Journal, 43, pp. 189 –190. Copyright 2000 by the Academy of Management. Reprinted with permission. a Items retained for the shortened measure that we used in the current study. Appendix B Appendix C Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results for Tepper’s (2000) Abusive Supervision Measure Supervisor-Directed Deviance Measure Model 2 df 2-factor 1-factor 195.40 336.92 34 35 ⌬2 CFI NFI RMSEA 141.52*** .96 .95 .96 .94 .11 .16 Note. N ⫽ 338. All chi-square values are significant at p ⬍ .001. CFI ⫽ comparative fit index; NFI ⫽ normed fit index; RMSEA ⫽ root-meansquare error of approximation. Data are from Tepper et al. (2004). *** p ⬍ .001, two-tailed. Item 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Made fun of my supervisor at work. Played a mean prank on my supervisor. Made an obscene comment or gesture toward my supervisor. Acted rudely toward my supervisor. Gossiped about my supervisor. Made an ethnic, religious, or racial remark against my supervisor. Publicly embarrassed my supervisor. Swore at my supervisor. Refused to talk to my supervisor. Said something hurtful to my supervisor at work. Note. Supervisor-directed deviance items were adapted from the following scales. Items 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 10 are from Bennett & Robinson (2000), p. 360. Items 5, 8, and 9 are from Aquino et al. (1999), p. 1082. Received January 30, 2005 Revision received October 24, 2006 Accepted October 25, 2006 䡲