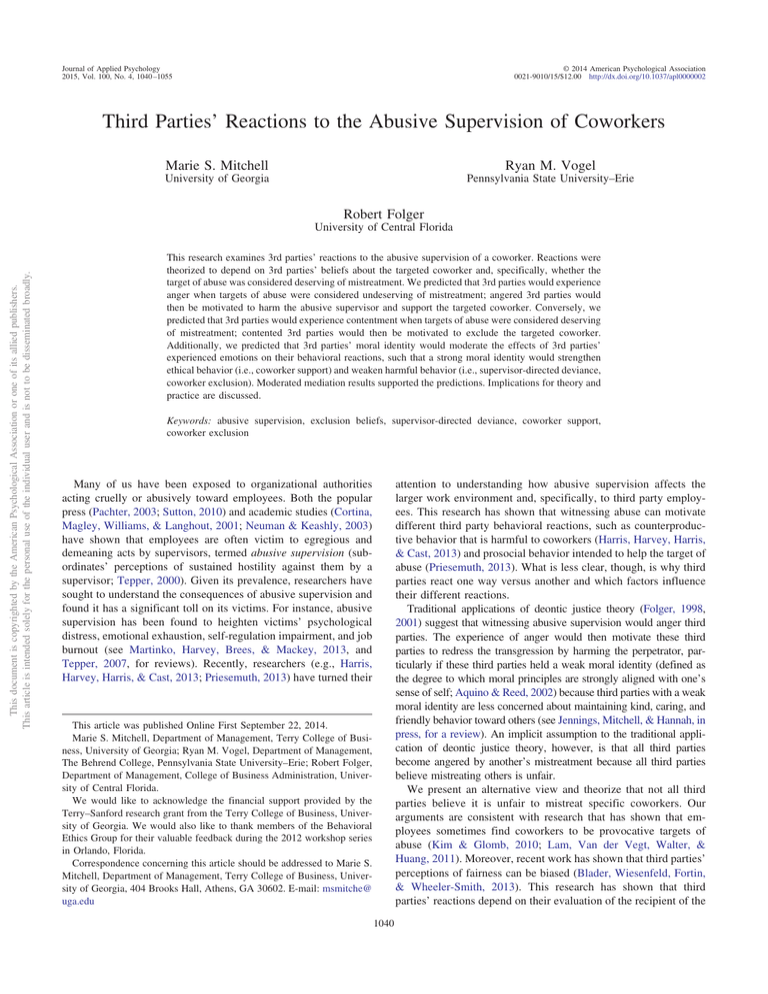

Third Parties’ Reactions to the Abusive Supervision of Coworkers Robert Folger

advertisement