UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013

advertisement

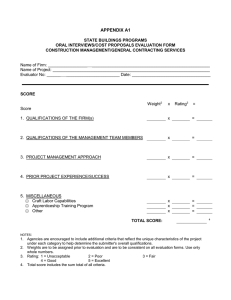

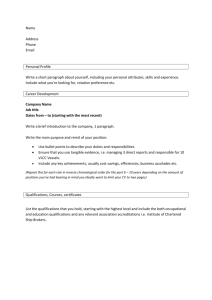

UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Evidence Report 85 August 2014 [This page is intentionally left blank] UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Derek L. Bosworth Associate Fellow, Warwick Institute for Employment Research UK Commission for Employment and Skills August 2014 [This page is intentionally left blank] UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Foreword The UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES) is a publicly funded, industry-led organisation providing leadership on skills and employment issues across the UK. Together, our Commissioners comprise a social partnership of senior leaders of large and small employers across from across industry, trade unions, third sector, further and higher education and across all four UK nations. Our Vision is to create with industry the best opportunities for the talents and skills of people to drive competitiveness, enterprise and growth in a global economy. Our Ambition for 2014-17 is to: Create more opportunities for all young people to get in and on in work; Improve the skills, productivity and progression of those in work; Build stronger vocational pathways into higher level skills and jobs. The UK Commission pursues a strongly evidence-based approach, drawing on impartial and robust national and international business and labour market research to inform choice, practice and policy. Uniquely, we combine robust business intelligence with Commissioner leadership and insight. Our research programme provides a robust evidence base for our insights and actions, drawing on good practice and the most innovative thinking. The research programme is underpinned by a number of core principles including the importance of: ensuring ‘relevance’ to our most pressing strategic priorities; ‘salience’ and effectively translating and sharing the key insights we find; international benchmarking and drawing insights from good practice abroad; high quality analysis which is leading edge, robust and action orientated; being responsive to immediate needs as well as taking a longer term perspective. We also work closely with key partners to ensure a co-ordinated approach to research. i UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 This report provides an updated assessment of the UK’s recent progress and projected future performance with regard to the skills held by the adult population. Within the report formal qualification attainment is used as a proxy for skill levels. Over the last decade, the UK has made significant progress in growing the skills of its workforce, greatly increasing the proportion with higher qualifications whilst reducing the proportion with no qualifications. However, when the UK’s performance is set in an international context it becomes clear that other nations are also making rapid advances. At current rates of progress relative weaknesses in the UK’s skills base will not be rectified. This is a real concern when viewed in the context of the UK’s overall competitiveness in global markets. Sharing the findings of our research and engaging with our audience is important to further develop the evidence on which we base our work. Evidence Reports are our chief means of reporting our detailed analytical work. All of our outputs can be accessed on the www.Gov.uk/ukces website. But these outputs are only the beginning of the process and we are engaged in other mechanisms to share our findings, debate the issues they raise and extend their reach and impact. We hope you find this report useful and informative. If you would like to provide any feedback or comments, or have any queries please e-mail info@ukces.org.uk, quoting the report title or series number. Lesley Giles Deputy Director UK Commission for Employment and Skills ii UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................. v Introduction ........................................................................................................................... v UK results ............................................................................................................................. vi International comparative qualification performance ..................................................... vii 1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 2 UK historical trends and projections to 2020 ............................................ 3 3 4 2.1 Recent historical trends.......................................................................................... 3 2.2 Projections to 2020.................................................................................................. 5 2.3 The rate of improvement......................................................................................... 6 2.4 Gender differences .................................................................................................. 8 The UK’s international comparative qualification performance .............. 9 3.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 3.2 Current levels of qualifications and recent progress ........................................ 10 3.3 Projections of attainment in 2020 (and beyond) ................................................ 13 Conclusions ............................................................................................... 15 Appendix A: The models used to project the profile of qualifications .......... 18 Annex A: Qualification levels ............................................................................ 22 iii UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Table of Graphs and Charts Figure 1: Historical trends in qualification mix (19-64 year olds, %) ......................................... 4 Table 1: Changing distribution of qualifications in the UK (19-64 year olds) ........................... 4 Table 2: Projected distribution of qualifications in the UK, 2020 (19-64 year olds) ................. 5 Table 3: Consecutive projections, 2020........................................................................................ 6 Table 4: Gender differences, 2012 and 2020, 19-64 year olds .................................................... 8 Table 5: Current international skills position ............................................................................. 11 Table 6: International skills projections 2020 ............................................................................ 12 iv UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Executive Summary Introduction This report provides an assessment of the level of skills held by the UK population compared to other countries. Skills play a fundamental role in determining individual employability and earnings potential and they make a major contribution to productivity and business profitability, ultimately contributing to economic growth. The rapid changes taking place in the global environment mean that the goal of achieving world class skills has never been more critical to UK jobs and growth and the future skills mix of the UK adult population is therefore of key importance. . The report builds on previous analyses of skill levels presented in the Ambition 2020 reports of 20091 and 20102 and Bosworth (2012)3. It assesses skills supply using possession of formal qualifications as the key measure, recognising that qualifications are only one, imperfect, measure of skills. Nonetheless, this analysis of the level of formal qualifications held by individuals provides a valuable insight into the UK’s skills performance. The reader should bear in mind that these projections indicate what would happen in the future if recent trends, which themselves are based on survey observations, continue. Many factors might influence these trajectories through to 2020 and beyond, so as with all projections, they should be treated with caution, as indicative of future trends rather than as precise forecasts of the future. This report provides an interim update of the results from the projections. A fuller analysis, including projections for the UK nations and English regions, will be published later in 2014. 1 UKCES (UK Commission for Employment and Skills) (2009) Ambition 2020: World Class Skills and Jobs for the UK. The 2009 Report. UKCES, Wath-upon-Dearne. 2 UKCES (UK Commission for Employment and Skills) (2010) Ambition 2020: World Class Skills and Jobs for the UK. The 2010 Report. UKCES, Wath-upon-Dearne. 3 Bosworth, D. (2012) UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness. UKCES, Wath-upon-Dearne. v UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 UK results The last 10 years (2002-2012) have seen a marked shift towards attainment at the highest qualification levels4 (Level 4 and above) and away from those without formal qualifications or qualifications at the lowest levels (less than Level 2). The proportion of the adult population5 qualified at a high level increased from 25.7 per cent to 37.1 per cent, whilst the proportion with no qualifications or low level qualifications as their highest qualification fell from more than one third (34.8 per cent) to less than a quarter (23.9 per cent). These historical trends are largely carried forward in the projections to 2020. The rate of improvement is lower for the below Level 2 category and slightly higher at Level 4+.6 Over the period 2012 to 2020, the proportion qualified to Level 4+ is projected to rise to 46.7 per cent (an increase of 9.6 percentage points or 4.2 million individuals), while the proportion below Level 2 is projected to fall to less than a fifth (17.7 per cent) of the population (a fall of 6.2 percentage points or 2.2 million fewer people at this level). There are important gender differences in projected qualification performance, with current trends suggesting that women can be expected to perform more strongly at both ends of the skills spectrum. A slightly higher proportion of females than males are currently qualified below Level 2 (24.3 per cent versus 23.3 per cent respectively) but females are projected to see a much more pronounced fall in the low skilled in the period to 2020 of nine percentage points, compared with a fall of only three points for males. By 2020 only 15.4 per cent of females are expected to be qualified below Level 2, compared with 20.0 per cent of males. With regard to higher level qualifications females already perform better than males, with 38.3 per cent qualified at Level 4 and above compared with 35.7 per cent of males. The projections indicate that this gap will widen slightly in the period to 2020 as female attainment at this level increases to 48.8 per cent compared with 44.6 per cent for males. 4 An explanation of the levels used in the report is provided at Annex A. Qualifications are defined here with reference to the Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF). This is the national credit transfer system for vocational qualifications in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. This framework defines formal qualifications by their level (i.e. level of difficulty) and credit value (how much time the average learner would take to complete the qualification). Scotland has its own qualification framework, the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF), and its own system of levels. Correspondences between the levels used in QCF / NQF and the SCQF are mapped in Qualifications can cross boundaries (SCQF, 2011). 5 The results outlined here are for 19-64 year olds unless otherwise stated. 6 Note that part of the increase in Level 4+ is caused by corrections to the immigrant data introduced in 2011. vi UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 International comparative qualification performance Analysis of the current international skills position and the latest projections to 2020 for 2564 year olds paint a mixed picture of the UK’s international ranking relative to 33 other member countries of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).7 Skills attainment is classified according to three levels: Low skills (Below Upper Secondary), Intermediate skills (Upper Secondary) and Higher skills (Tertiary)8. For Low skills the UK is currently ranked 19th (i.e. there are 18 out of the 33 other countries with lower proportions); this places it in the third quartile of nations and just behind the averages of both the OECD and EU. The UK is not expected to see an improvement in its poor relative performance in the period to 2020, based on current trends. Although the proportion qualified below upper secondary level is projected to fall from 26 per cent to 18 per cent this would leave the UK three places lower in the rankings because of more rapid improvement by other nations. 37 per cent of the UK’s adult population are currently qualified at Intermediate level (Upper Secondary), giving a ranking of 24th out of 33 OECD nations. The proportion qualified at this level is projected to decline slightly (to 34 per cent) in the period to 2020, resulting in a fall in the UK’s ranking to 28th. Conversely, the proportion of the UK’s adult population qualified at a Higher (Tertiary) level is projected to increase significantly, from 37 per cent to 48 per cent in the period to 2020, elevating the UK’s international ranking slightly, from 11th to 7th. This points towards a consolidation of the UK’s position on high level skills but it is important to bear in mind that the projected position of the UK in 2020 is based on a continuation of existing trends. It seems highly likely that at least some nations will see an improvement in the “trajectory” of their performance as a result of policy intervention and / or other factors, such as increased demand for higher level skills within their national labour markets. From this analysis it could be argued that the most pressing priority is to accelerate the rate of reduction in the size of the long “tail” of the low skilled in the UK population; both by supporting the progression of those already in the labour force and helping them to move up into the intermediate band, as well as by minimising the proportion of new entrants to the labour market who lack attainment at upper secondary level. 7 Note that the current OECD data are for 2011 and are compared with the LFS data for 2011. This and the difference in the age group means that the results discussed here are not directly comparable with the earlier tables. 8 These levels correspond broadly with below QCF level 2 (Low), QCF levels 2-3 (Intermediate) and QCF level 4 and above 8 (High) . vii UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Although there is a fairly clear imperative to minimise the proportion of the labour force who are skilled to a low level it is less clear what the optimal split between intermediate and high level skills should be. Different countries have different strategies for growth. The UK’s key strength lies in the size of its pool of high skilled labour. In contrast, countries like Germany have founded a successful economic strategy on a skills base that is weighted towards Intermediate skills, with a relatively small proportion qualified at a Higher level (but also only a small proportion of the population holding no qualifications or low level qualifications). Clearly, the level of skills and qualifications available in the economy is only one consideration; the relevance of those skills to business and the ability of organisations to utilise them effectively are also key. viii UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 1 Introduction Amidst the signs of a continuing recovery there is a widespread consensus that the UK needs to undergo a structural rebalancing of its economy if it is to achieve longer term growth and prosperity. A crucial condition of sustainable growth is the availability of people with the capabilities businesses need to compete in international markets. The rapid changes taking place in the global environment mean that the goal of achieving world class skills has never been more critical and at the same time more difficult to achieve. Many competitor nations in the developing world are investing heavily in their skills base in order to support a move up the value chain and to build a presence in markets that have traditionally been dominated by developed nations like the UK. This means that not only does the UK need to “run to stand still” in terms of it relative performance on skills; the projections suggest that even improvements in absolute terms could still lead to a fall in the international rankings. The future skills mix of the UK adult population is of critical importance. The increased pace of globalisation and technological change, the changing nature of work and the labour market, and the ageing of populations are among the forces driving demand for skills. Skills play a fundamental role in determining individual employability and earnings potential, and make a major contribution to the productivity and profitability of business. For the economy, there is a positive relationship between attainment and economic growth9. The present report deals with the issue of the profile of skills, as proxied by formal qualifications, in the UK. It presents historical changes and trends, as well as projections through to 2020. The approach used to assess likely future performance is set out in Appendix A. This report updates and builds on previous work by the UK Commission to assess the international skills challenge, as presented in its Ambition 2020 reports for 2009 and 2010 and in Bosworth (2012), using an approach designed to provide results that are consistent with this prior analysis. 9 See, for example, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2004) Lifelong Learning: Policy Brief. OECD, Paris. 1 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Some care is needed when talking about the supply of qualifications. In the present report “supply” relates to the qualifications held by the UK population at different points in time. Changes to supply are shaped by individual perceptions at each point in time about what the demand for qualifications and skills will look like in the future (e.g. how many jobs will there be requiring the associated higher qualifications and skills, and what wage premia will be attached to such jobs). As with all projections and forecasts, the forward-looking results presented in this report should be regarded as indicative of likely trends, given a continuation of past patterns of behaviour and performance, rather than precise forecasts of the future. In addition, the chief source upon which the projections are based is the Labour Force Survey (LFS). Like all surveys, the LFS is subject to sampling error: a degree of inaccuracy caused by observing a sample instead of the whole population. The impact of this issue on the projections is considered in more detail in the technical appendix to this report and in the accompanying technical reports. This report assesses skills supply using possession of qualifications as the key measure and skills and qualifications are often treated as being synonymous. This approach has the advantage that qualifications are easy to count, and data are readily available. However, it is recognised that qualifications are only one, imperfect, measure of skills. There are many individuals who possess skills that are highly valued by employers but who hold no formal qualifications. On the other hand employers may be sceptical of the value of some qualifications. Moreover, a general improvement in qualification levels is of limited benefit if it is not accompanied by the development of the ‘right’, economically valuable skills, which employers demand and which can be effectively deployed in the workplace. Nonetheless, this analysis of the level of formal qualifications held by individuals is felt to provide a valuable insight into relative performance of the UK’s skills base. 2 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 2 UK historical trends and projections to 2020 The main UK qualifications modelling draws on a linear time series model. This model uses historical Labour Force Survey (LFS) data, broken down by gender and year of age (for those of working age) for six qualification levels (see Annex A for further information on levels). Individuals are allocated to a particular qualification level according to the highest qualification they hold. 2.1 Recent historical trends Figure 1 and Table 1 set out the main historical trends. Figure 1 indicates the considerable improvement that has occurred at Level 4 and above. In particular, the number of people qualified at Level 7-8 almost doubled in absolute size over the period, although Levels 4-6 saw the greater increase in share. The proportion of the adult population qualified at intermediate levels remained largely constant over the period. There were increases in the numbers of people qualified at Level 2 and particularly at Level 3 but, in terms of share, this was offset by increases in total population size. Declines took place at Level 1 and amongst those with no qualifications (4 and 7 percentage points respectively). 3 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Figure 1: Historical trends in qualification mix (19-64 year olds, %) 40 35 % of adult population 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 2002 2003 2004 2005 No qualifications 2006 2007 Level 1 2008 Level 2 2009 2010 Level 3 2011 2012 Level 4+ Source: Time series model Table 1 highlights the size of these changes in terms of the numbers of individuals involved. Over the ten year period, the number of individuals with Level 4+ rose by more than 5 million (an 11 percentage point rise), while those below Level 2 fell by more than 3 million (an 11 percentage point fall). These changes took place against a population increase amongst 1964 year olds of nearly 3 million. Table 1: Changing distribution of qualifications in the UK (19-64 year olds) 2002 Level 7-8 Level 4-6 Level 4+ Level 3 Level 2 Level <2 Level 1 No Qualifications All qualifications 2012 2002-2012 Change % Nos (‘000s) % Nos (‘000s) Percentage point 4.7 21.0 25.7 19.2 20.3 34.8 19.0 15.8 100.0 1,662 7,490 9,152 6,835 7,217 12,394 6,775 5,619 35,599 8.3 28.8 37.1 19.4 19.7 23.9 14.7 9.2 100.0 3,190 11,024 14,214 7,446 7,534 9,144 5,627 3,516 38,337 3.7 7.7 11.4 0.2 -0.6 -11.0 -4.4 -6.6 0.0 Nos (‘000s) 1,528 3,533 5,061 610 316 -3,250 -1,148 -2,102 2,738 Source: Time series model. Note: “No qualifications” are all individuals below Level 1 and, therefore, include some individuals with Entry Level qualifications. 4 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 2.2 Projections to 2020 The projections of future qualification levels are undertaken separately for males and females, by year of age (16 to 69), using either the last 10 years of historical data or the last five years. These projections simply indicate what would happen in the future if recent trends continue, and many things might impact on their path through to 2020 and beyond, so considerable caution is needed in using these results. The results based upon the trends over the ten years, 2003 to 2012, are set out in Table 2. It can be seen that the proportion qualified to Level 4+ is projected to rise from 37.1 to 46.7 per cent over this period (a 9.6 percentage point increase). The projections suggest that Level 7-8 will continue to be the fastest growing area. The largest fall is in those with no qualifications (a reduction in share of 3.7 percentage points, or a fall of 40 per cent compared with its 2012 value), which comprises the majority of the 6.2 percentage point fall in the below Level 2 group. In fact all levels of qualification other than the highest two show falls, although some of these are quite modest. The projections suggest that there will be a fall of just less than 1 million people at the intermediate levels (Levels 2 and 3). Table 2: Projected distribution of qualifications in the UK, 2020 (19-64 year olds) 2012 2020 2012-2020 Change % Nos (‘000s) % Nos (‘000s) Percentage point Level 7-8 8.3 3,190 11.4 4,483 3.0 1,293 Level 4-6 28.8 11,024 35.3 13,933 6.6 2,910 Level 4+ 37.1 14,214 46.7 18,416 9.6 4,202 Level 3 19.4 7,446 17.5 6,884 -2.0 -562 Level 2 19.7 7,534 18.2 7,164 -1.5 -369 Level <2 23.9 9,144 17.7 6,980 -6.2 -2,163 Level 1 14.7 5,627 12.1 4,767 -2.6 -861 No Qualifications 9.2 3,516 5.6 2,214 -3.7 -1,303 All qualifications 100 38,337 100 39,445 0 1,108 Nos (‘000s) Source: Time series model. Note: “No qualifications” are all individuals below Level 1 and, therefore, include some individuals with Entry Level qualifications. Comparing the results in Table 1 and Table 2, it can be seen that the rise in the number of individuals holding Level 4+ is projected to be smaller in absolute terms over the period 2012 to 2020 than over 2002 to 2012 (4.2 compared with 5.1 million).. 5 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 The fall in below Level 2 is only two-thirds of that seen in the decade to 2012 (2.2 compared with 3.3 million). This increase in the absolute number of those at Level 4 or above takes place over the shorter projection period is roughly in line with the increase from 2002 to 2012 and takes place against a background in which the increase in the UK population of age 1964 over the projected period to 2020 is much less than in the previous 10 years (1.1 compared with 2.7 million). 2.3 The rate of improvement It is difficult to say anything about private or public policies and their effects on qualification mix per se, but it is possible to say whether the historical trends at different points in time suggest that more recent projections are in some sense “more favourable” than earlier projections. The time series modelling has been carried out over a number of years and, while a number of changes have been made to the model, these will not have affected the overall results dramatically, allowing comparisons between them. As the model is estimated on the most recent ten years of data, each subsequent year of modelling differs by two years of data (the latest year is added into the historical data and, what was the tenth year, drops out). The first column of Table 3 shows the data periods. Table 3: Consecutive projections, 2020 Data period 2003-2012a 2001-2010b 2000-2009c 1999-2008d Level <2 Level 4+ % 000’s % 000’s 17.7 19.9 19.7 19.3 6,980 7,858 7,776 7,601 46.7 44.4 43.8 41.7 18,416 17,496 17,289 16,462 Notes: a) current report; b) Bosworth (2012); c) unpublished report; c) Ambition 2020, 2010 Report 6 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 What Table 3 shows is whether there have been any systematic changes to the forecasts over time as new data have emerged. The results in Table 3 show a great deal of stability, as would be expected, as each model shares eight years of data with its immediate predecessor. Previous results suggested that, over time, a modest polarisation of qualification levels was taking place, as the proportion below Level 2 in 2020 rose from 19.3 to 19.9 per cent and Level 4 and above rose from 41.7 to 44.4. This implied that the trend towards higher level qualifications (Level 4 and above) had been accelerating whilst the proportion of individuals with lower level (less than Level 2) or no qualifications would see a smaller fall than indicated by the first set of projections. However, the latest set of results suggest a change in this trend. Whilst the projected share of higher qualified individuals has increased further11, the proportion of unqualified and low qualified individuals is projected to fall to the lowest level since the forecasting work began. This could suggest that public and private efforts to reduce the UK’s “tail” of poorly qualified individuals are meeting with some success. 11 Although this is driven in part by changes to the treatment of foreign qualifications, which particularly affected Level 4+. 7 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 2.4 Gender differences The model is estimated separately for males, females and all individuals13 and Table 4 reports the main differences in the mix of qualifications and the changes in the mix over the projection period for those aged 19-64. Females start in 2012 with a higher proportion of individuals at Level 4 and above than is the case of males (38.3 per cent compared with 35.7 per cent). Females are projected to have a considerably greater improvement at Level 4-6 than males in the period to 2020, with little difference in the improvement in Level 7-8, meaning that the gap between the genders widens, with 48.8 per cent of females at Level 4 or above, compared with 44.6 per cent of males. Table 4: Gender differences, 2012 and 2020, 19-64 year olds Males Level 7-8 Level 4-6 Level 4+ Level 3 Level 2 Level <2 Level 1 No Qualifications 2012 (% share) 2020 (% share) 8.3 27.4 35.7 21.4 19.6 23.3 14.6 8.7 100 11.3 33.3 44.6 17.0 18.4 20.0 14.1 5.8 100 Females pp change 3.0 5.9 8.9 -4.5 -1.2 -3.3 -0.5 -2.8 0 All individuals 2012 (% share) 2020 (% share) pp change 2012 (% share) 2020 (% share) pp change 8.2 30.0 38.3 17.5 19.9 24.3 14.8 9.6 100 11.4 37.4 48.8 18.0 17.9 15.4 10.0 5.4 100 3.2 7.4 10.5 0.4 -1.9 -8.9 -4.7 -4.2 0 8.3 28.8 37.1 19.4 19.7 23.9 14.7 9.2 100 11.4 35.3 46.7 17.5 18.2 17.7 12.1 5.6 100 3.0 6.6 9.6 -2.0 -1.5 -6.2 -2.6 -3.6 0 All qualifications Source: Time series model. Note: “No qualifications” are all individuals below Level 1 and, therefore, include some individuals with Entry Level qualifications. Turning to the bottom half of the table, a slightly higher proportion of women than men had less than Level 2 qualifications in 2012: 24.3 compared with 23.3 per cent. However, the downward trend in this proportion is much stronger for females than for males (changes of 8.9 and 3.3 percentage points for females and males respectively), such that, by 2020, only 15.4 per cent of women fall into this low qualifications group, compared with 20.0 per cent of males. 13 The all individual result is not a weighted average of males and females and is a check whether the results are broadly consistent (e.g. does the figure for all individuals lie between the male and female results). 8 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 3 The UK’s international comparative qualification performance 3.1 Introduction There is clear evidence that the skills available in the labour force help to determine how countries will fare in the global marketplace. As products and processes become more complex, the requirement for workers with a higher level of knowledge and skills grows. Increasing attainment levels in the population lead to increased earnings for individuals, contributing to national growth and prosperity. For example, analysis conducted by the OECD14 suggests that more than one half of the GDP growth in OECD countries over the past decade is related to earnings growth among individuals educated to a tertiary level. The contribution of high skilled individuals in the UK is estimated to be significantly higher than the OECD average. From this point of view it is valuable not only to assess current performance but also to understand what future performance may look like, based on an extrapolation of recent trends. The picture is not static: we know that competitor economies, including emerging nations, are making rapid progress in developing the skills of their people. The following analysis is based on an International Skills Model, which projects the educational attainment of the adult working-age population (aged 25-64) in OECD countries, distinguishing between: Low skills (Below Upper Secondary), Intermediate skills (Upper Secondary) and Higher skills (Tertiary).In an UK context these levels correspond broadly with below Level 2 (Low), Level 2-3 (Intermediate) and Level 4 and above (High)15. The model uses OECD data for the most recent 10 years (from 2002 to 2011), to identify trends in changes in educational attainment for the countries for which data are available16. The model uses historical trends to generate stylised international education level projections to 202017. 14 OECD (2013), Education at a Glance 2013: Highlights, OECD Publishing. DOI :10.1787/eag_highlights-2013-en 15 It should be noted that while there is likely to be considerable overlap, at least for the UK, the match is still unlikely to be perfect and, in addition, there are numerous problems with regard to consistency in such international comparisons. See the technical report for further details. 16 Further details are provided in Appendix A. 17 The methodology is set out in Bosworth, D.L. (2012). International Skills Model: Technical Report, 2012. IER. University of Warwick. 9 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 To provide consistency with the approach used in the Ambition 2020 analyses of 2009 and 2010 and with Bosworth (2012) we have included data from the main time series model for the UK and nations outlined in Section 2 above, rather than the simple time series for the UK based upon the OECD results18. The projections provide a starting point for assessing whether the likely trajectories indicate that the UK’s comparative international adult skills position will improve or deteriorate over the projection period. Countries are ranked according to their most recent position19 and in 2020 in terms of: The proportion of Low skills (lowest to highest) The proportion of Intermediate skills (highest to lowest); and The proportion of High skills (highest to lowest). In general, given that productivity and earnings are positively linked to educational attainment, there is a general tendency to think in terms of a small proportion of Low skills (relative to Intermediate and High skills) and large proportion of High skills (relative to Low and Intermediate skills) as being “good”. For simplicity, this is the interpretation adopted below. In practice, whether changes in the three proportions should be said to be “good” or “bad” may depend on the different countries’ strategies for growth and other dimensions of well-being, which may require a more complex outcome in terms of the proportions of individuals at different education levels. As is clear from the following tables, relatively small differences in proportions (per cent qualified) can have a major impact on a country’s ranking against any of the three indicators. 3.2 Current levels of qualifications and recent progress This section discusses the UK’s current position, based upon the most recent data – see Table 5 – and discusses how this differs from the then current position reported in Bosworth (2012)20. 18 Note, however, that the results discussed here differ from those in Section 2 insofar as they relate to individuals aged 25-64, rather than 19-64 as previously, in order to correspond with the age coverage of the OECD data. 19 Data for the UK are taken from the main time series model which draw on Labour Force Survey data for 2012 for the projections; data for 2011 are used for comparative purposes in the current international skills position table (Table 5). Data for the other 32 countries is taken from OECD data for the period up to and including 2011. The data are for 25-64 year olds and, hence, are not directly comparable with the earlier tables. 20 UK Commission (2010). Ambition 2020: World Class Skills and Jobs for the UK. The 2010 Report. UK Commission for Employment and Skills. 10 Table 5: Current international skills position Low skills (Below upper secondary) Country Japan Czech Republic Slovak Republic United States Poland Estonia Canada Sweden Germany Switzerland Slovenia Finland Israel Austria Norway Hungary Korea Denmark EU21 average OECD average UK New Zealand Australia Ireland Netherlands France Belgium Iceland Luxembourg Greece Italy Spain Mexico Portugal Turkey Intermediate skills (Upper secondary) % Qualified Rank 7 7 9 11 11 11 11 13 14 14 16 16 17 18 18 18 19 23 24 25 26 26 26 27 28 28 29 29 30 33 44 46 64 65 68 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 n/a n/a 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Country Czech Republic Slovak Republic Poland Austria Hungary Slovenia Germany Estonia Sweden Switzerland EU21 average United States Japan Finland OECD average Norway Denmark France Italy Greece Korea Luxembourg Netherlands Canada Iceland UK Belgium Israel Australia Ireland New Zealand Spain Mexico Turkey Portugal % Qualified 74 73 65 63 61 59 59 52 52 50 48 47 47 44 44 44 43 42 41 41 41 41 40 37 37 37 37 37 36 36 35 22 19 18 17 Source: OECD Education Database and Labour Force Survey, ONS Note: Distribution of the 25–64 year old population by highest level of education attained. Excludes Chile. . 11 Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 n/a 11 12 13 n/a 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 High skills (Tertiary) Country Canada Japan Israel United States Korea New Zealand Finland Australia Norway Ireland UK Estonia Switzerland Sweden Belgium Iceland Denmark Spain Netherlands OECD average France Luxembourg EU21 average Germany Greece Slovenia Poland Hungary Austria Slovak Republic Czech Republic Mexico Portugal Italy Turkey % Qualified 51 46 46 42 40 39 39 38 38 38 38 36 35 35 35 34 34 32 32 32 30 30 29 28 26 25 24 21 19 18 18 17 17 14 14 Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 n/a 20 21 n/a 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Table 6: International skills projections 2020 Low skills (Below upper secondary) Country Japan Czech Republic Slovak Republic Poland Canada Sweden Finland Hungary Korea Slovenia United States Norway Estonia Germany Ireland Switzerland Australia Austria Israel EU21 average Belgium New Zealand OECD average UK Denmark Luxembourg Greece Iceland France Netherlands Spain Italy Portugal Mexico Turkey % Qualified 5 5 5 5 5 7 7 7 8 8 9 9 10 11 11 12 12 13 15 16 17 17 18 18 19 19 20 21 21 21 33 33 55 57 61 Intermediate skills (Upper secondary) Rank 1 1 1 1 1 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 n/a 20 21 n/a 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Country % Qualified Czech Republic Slovak Republic Hungary Austria Poland Germany Slovenia Sweden EU21 average Greece Finland Estonia Italy Denmark Norway United States Japan OECD average France Belgium Switzerland Australia Netherlands Iceland Luxembourg Korea Ireland Israel Canada UK New Zealand Spain Mexico Portugal Turkey 73 71 65 62 61 59 57 50 48 48 47 47 47 46 45 44 44 43 43 42 41 41 39 39 37 37 37 36 35 34 31 29 24 22 21 Source: UKCES projections based on OECD Education Database and Labour Force Survey, ONS Note: Distribution of the 25–64 year old population by highest level of education attained. Excludes Chile. 12 High skills (Tertiary) Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 n/a 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 n/a 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Country Canada Korea Ireland Japan New Zealand Israel UK Switzerland Australia United States Norway Finland Luxembourg Sweden Estonia Belgium Iceland Netherlands OECD average Spain EU21 average France Denmark Slovenia Poland Greece Germany Hungary Austria Slovak Republic Portugal Czech Republic Italy Mexico Turkey % Qualified 60 55 52 52 51 49 48 47 47 47 46 45 43 43 43 42 41 40 39 38 36 36 35 34 34 32 30 28 24 24 23 23 20 19 19 Rank 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 n/a 19 n/a 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 For Low skills (Below Upper Secondary level) the UK is currently ranked 19th (i.e. there are 18 out of the 33 other countries with lower proportions qualified at this level). This places the UK in the third quartile of nations and underperforming relative to the averages for both the OECD and EU. This ranking of 19th is two places higher than in the 2012 report, with Netherlands and New Zealand slipping behind the UK. 37 per cent of the UK’s adult population are currently qualified at Intermediate level (Upper Secondary), giving a ranking of 24th out of 33 OECD nations. This represents an improvement of one place over the position in the 2012 report but still leaves the UK well below both the OECD and EU averages. Over this period Iceland has overtaken the UK (moving from a ranking of 28th to 23rd), whilst Belgium has fallen below the UK in the ranking (moving from 23rd to 25th place) as has Israel (24th to 26th place). Finally, in terms of the change in ranking for High skills, the UK has improved its position from 13th to 11th, as a result of overtaking Estonia and Switzerland in the rankings. The UK is placed well ahead of the averages for the OECD and EU in respect of this indicator. 3.3 Projections of attainment in 2020 (and beyond) The UK is not expected to see an improvement in its poor relative performance on Low skills in the period to 2020, based on current trends. Although the proportion qualified below upper secondary level is projected to fall from 26 per cent to 18 per cent (compare Table 5 and Table 6) this would leave the UK three places worse off in the rankings (falling from 19th to 22nd) because of a more rapid improvement by other nations. The projections indicate that Ireland, Australia, Belgium and New Zealand overtake the UK in the period to 2020, whilst Denmark is overtaken by the UK. More positively, this still represents an improvement compared with the results of the 2012 report (Bosworth, 2012), which indicated that the UK could expect to be ranked in 25th place. The projected estimate that 18 per cent of the adult population will be qualified at this level by 2020 is a slight improvement on the 19 per cent estimate in the previous report. The proportion qualified at Intermediate level (Upper Secondary) is projected to decline slightly (from 37 per cent to 35 per cent) in the period to 2020, resulting in a decline in the UK’s ranking from 24th to 28th out of 33 OECD nations. The UK is overtaken by Ireland, Australia, Israel and Belgium, based on the projections. 13 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 The UK is ranked two places lower in the current projections than in the results of the 2012 report, which ranked it in 26th place on Intermediate attainment, although the proportion qualified at this level in 2020 is only one percentage point lower in the present set of projections, at 34 per cent. Conversely, the proportion of the UK’s adult population qualified at the Higher (Tertiary) level is the only one of the three levels that is projected to see an increase in its share of the adult population between 2012 and 2020, with a significant increase from 37 per cent to 48 per cent. This improves the UK’s international ranking by four places, from 11th to 7th, as it overtakes Finland, Norway, the United States and Australia.21 The UK is ranked four places higher in the current projections compared with the results of 2012 report in which it was ranked 11th. The current set of projections indicate that 48 per cent of the adult population will be qualified at a higher level by 2020 compared to 46 per cent predicted by the prior projections. 21 Some care should be taken in interpreting this substantial projected increase in the share of Tertiary level and the associated UK ranking. The introduction of a new level of qualification question for immigrants has a significant positive impact on the numbers of the UK population at Level 4+ in 2011 and 2012 that may account for some of the improvement. Future changes to the model will allow more light to be thrown on this issue. 14 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 4 Conclusions Principal projections22 The focus of the present report has been on the levels of skills as proxied by formal qualifications, both historically and in terms of projections to 2020. The trends in qualifications over the 10 years to 2012 have been strongly in favour of the higher qualification levels (Level 4 and above) and away from the lowest qualification levels (less than Level 2). The number of individuals with Level 4+ rose by over 5 million (an 11.4 percentage point rise) while those below Level 2 fell by over 3 million (an 11.0 percentage point reduction). For the period to 2020 this broad pattern is projected to continue but with a slowing in the rate of change for the below Level 2. Over the period 2012 to 2020, the proportion of the adult population qualified to Level 4+ is projected to rise from 37.1 to 46.7 per cent (a ten percentage point increase over a nine year period, associated with an additional four million individuals). Over the same period, the proportion below Level 2 is projected to fall from 23.9 to 17.7 per cent (a six percentage point fall, associated with about 2.1 million fewer people at this level). It should be borne in mind that these are linear projections which indicate what is likely to happen if recent trends continue into the future. Previous reports have shown that, as the ten year historical period has been moved over the sequence of projections made for the UK Commission, the positive effect on the most highly qualified and negative effects on the least qualified have increased over time. The latest set of results suggest that this trend continues, as it projects that the proportion of unqualified and low qualified individuals will fall to the lowest level since the forecasting work began, whilst the proportion qualified at a high level increases again, although this may be partly due to a revision in the immigrant qualification data. 22 Unless otherwise indicated all numbers or proportions discussed below relate to 19-64 year olds. 15 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Gender With regard to gender, there are important gender differences both in the projected changes and in the levels, both in 2012 and 2022. Females start with a higher proportion of Level 4+ in 2012 than males (38.3 per cent compared with 35.7 per cent) and are projected to have a larger increase at this level (11 percentage points compared with 9 points). While females start from a higher percentage of below Level 2 (24.3 per cent in 2012) compared with males (23.3 per cent), they have a much larger projected decline (9 points compared with 3 percentage points), which results in a much lower proportion of women at this level than men by 2020 (15.4 per cent compared with 20.0 per cent). The UK’s international comparative qualification performance The UK displays a mixed picture in terms of its current international performance on qualification attainment. Its strongest relative performance is in respect of High skills but it sits well down the rankings for Low skills and Intermediate skills attainment. In terms of Low skills, the UK is currently ranked 19th (i.e. there were 18 other countries in the OECD with a smaller proportion of people qualified at this level), but is projected to be 22nd by 2020, in spite of a reduction in the proportion of the population qualified at this level. With respect to Intermediate skills, attainment the UK is ranked 24th currently and is projected to fall to 28th place by 2020. Finally, the UK’s ranking in terms of the proportion of individuals with High level qualifications improves in the period to 2020, moving from 11th to 7th. This results from a substantial increase in the proportion of the population qualified at this level of around nine percentage points, but may be influenced by a change in the way in which immigrant qualification data are collected at the end of the historical period. What the present analysis cannot show is where each country actually will be by 2020 or 2025. The changes in rank are relatively small for the UK, unlike those of a number of other countries. It seems unlikely that a number of the countries showing deteriorations in their rankings will not react to address the adverse movements, although the costs involved in reducing the proportion of low skilled adults in the population, for example, can prove considerable. 16 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 There are also significant challenges involved in ensuring that increases in the aggregate supply of skills reflect the needs of national economies i.e. that the qualifications and skills acquired by individuals are economically valuable and are used in the workplace. The concerns that this issue raises are reflected in a series of current debates around the underutilisation of graduates in the workplace, trends in the earnings of the higher qualified and the emergence of skills shortages for high skilled roles. 17 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 Appendix A: The models used to project the profile of qualifications A.1 Introduction The present Report mainly draws upon two models of qualifications supply: the main UK “time series” qualifications model23; and The international time series education model24. The present discussion provides a brief introduction to the two models used directly in the present Report. A.2 Main “time series” qualifications model This model focuses on projecting the qualification distribution across all adults in the UK population through to the year 2020 (and to 2025). It is a linear time series model, which was developed by HM Treasury for the Leitch Review of long term skills needs25. This model uses historical Labour Force Survey (LFS) data, broken down by gender and year of age (currently for those aged 16 to 69) for six qualification levels26. Individuals are allocated to a particular qualification level mainly according to the highest qualification they hold (but, in some cases, individuals with more than one qualification are allocated to a higher group). The detailed procedures used to estimate the proportion of the population qualified at different levels using LFS data are set out in the technical report for the main time series model. Thus, as an example, the model projects the proportion of males aged 16 that have no qualifications, using the trends in such males over the period 2003 to 2012. It repeats this exercise for males of each age, from 16 to 69, and for each qualification level (no qualifications, QCF1, …, QCF3, QCF4-6 and QCF7-8). It then repeats this exercise for females and for males and females combined. The expectation is that the weighted sum of 23 Bosworth, D.L. (2012). UK Qualifications Projections – “Time Series” Model. Technical Report. (draft available from the author). 24 25 Bosworth, D.L. (2012). International Education Model, 2012. Technical Report. January. (draft available from the author). Prosperity for all in the Global Economy - World Class Skills. (see fn. 1). 26 Qualification and Credit Framework levels QCF1, QCF2, QCF3, QCF4-6 and QCF7-8, plus those with no qualifications. See Annex A. 18 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 the projections for males and females should take a similar value to the projections for all individuals combined. Various constraints are placed on the projections, for example, that: qualification proportions always sum to 100; qualification numbers always sum to the ONS 2010-based population projections across the different levels of the QCF. each qualification proportion always lies between 0 and 100; the proportion of those with no qualifications and QCF1 each have a lower limit of five per cent. There are several “special groups” that form a focus within the modelling process, in particular: those retiring and moving outside the labour force; migrants and, in particular, the net difference in qualifications between immigrants and emigrants. The retirement group is both interesting and challenging in terms of the modelling process. Prior to 2008, the LFS did not collect qualifications data from individuals over “retirement age” if they are not in employment27. Clearly, the changes to the earliest age of retirement for increasing numbers of people and the proposed changes for the future make it important to say something about the qualifications of older individuals who, historically, would have moved out of the labour force but, by 2020 and 2025 will be kept within it for longer periods. Given the lack of LFS data, this was done by modelling the changing qualification mix of individuals as they age from 50 to 59 for females and 60 to 64 for males, in order to say what the qualification mix of 60-69 year old females and 65-69 year old males looks like. The estimated qualifications mix for older individuals is projected forward in the same way as for younger. In future modelling exercises, sufficient years of data will be available, and the 60-69 year olds will be modelled in the same way as younger people. The effects of migration became a major issue over the last 20 years or so. The work attempts to model immigrant and emigrant groups separately from the main, non-migratory population of the UK. Immigrants are proxied by the group of individuals in the LFS who were not resident in the UK one year earlier. There are at least two major problems with this 27 Since 2008 the Labour Force Survey has extended its definition of working age, in respect of qualification variables, to include all individuals aged 16-69. However, since the projections draw on 10 years of historic data (2003-2012 in the current iteration) it is not yet possible to take advantage of this development. 19 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 group: first, while immigrant numbers can be quite large (e.g. circa 600,000), sample sizes in the LFS are quite small, especially when broken down by gender, year of age and qualification level; second, until 2011, the LFS allocated foreign qualifications to an “other” category. They were then allocated using a “rule-of-thumb”, based upon some fairly old General Household Survey data. Similarly, there is no direct survey information for the emigrant group in the LFS, so the assumption is made that this group has the same qualifications mix as the population as a whole. Thus, the main time series qualification model proceeds by subtracting out cumulative net migration from the UK population as a whole, before dealing separately with the qualifications of immigrants, emigrants and the non-migratory population. The historical trends in qualification mix for those not resident in the UK one year ago and for the UK population as a whole (proxying both the emigrant and non-migratory groups) are separately projected forward to 2020 (and 2025). These are translated into numbers of immigrants, emigrants and non-migrants, by level of qualification, from which the net migration numbers can be isolated by level of qualification. Net migration by qualification (year of age and gender) are then cumulated and added back to the projections of the non-migrant population. All figures are constrained to sum to the ONS 2010-based projections. A.3 International time series educational model The international time series model takes the data from the OECD Education Database (formerly Education at a Glance)28 as the principal input. These data are the proportions of the population aged 25 to 64 with educational attainments at Low (Below Upper Secondary), Intermediate (Upper Secondary) and High (Tertiary) levels.29 The data were revised to give a much more consistent historical series a couple of years ago; since then, however, a small number of problems appear to have crept back in. The modelling simply takes the most recent ten years of data (at the time of writing 2002 to 2011) and fits linear trends which are then used to project forward the proportions of individuals at the three education levels through to 2020 and beyond. All projections are constrained so they sum to 100 for each country. The UK projections, however, are from the model described in A.2 above, reporting only the 25-64 year old results. 28 http://www.oecd.org/document/2/0,3746,en_2649_39263238_48634114_1_1_1_1,00.html These levels correspond broadly with below QCF2, QCF2-3 and QCF4 and above respectively. However, while there is likely to be considerable overlap, at least for the UK, the match is still unlikely to be perfect and, in addition, there are numerous problems with regard to consistency in such international comparisons. 29 20 UK Skill Levels and International Competitiveness, 2013 A number of countries pose particular problems; for example, Japan does not distinguish the separate results for Low and Intermediate levels (i.e. they only report the combined results for Below Upper Secondary / Upper Secondary alongside the Tertiary group). The combined groups are separated using increasingly out-of-date information – so Japan’s results should be treated with caution. A number of countries do not have complete time series data for the historic period. For example, an extreme case is Chile, which first participated in the Education Database in 2009 and only provided three years of data. While it is a fairly easy decision to omit Chile from the comparator group because it is not possible to make sensible projections from just two observations, other decisions on inclusion and exclusion are more difficult. As a rule of thumb, as many countries as possible have been included, even if this means adjustments to the historical data have to be made or somewhat shorter historical periods of data have to be utilised. 21 A Annex A: Qualifica ation leve els S Source: Qualificatiions can cross bo oundaries – a roug gh guide to compa aring qualifications s in the UK and Irreland 22 List of previous publications Executive summaries and full versions of all these reports are available from www.ukces.org.uk Evidence Report 1 Skills for the Workplace: Employer Perspectives Evidence Report 2 Working Futures 2007-2017 Evidence Report 3 Employee Demand for Skills: A Review of Evidence & Policy Evidence Report 4 High Performance Working: A Synthesis of Key Literature Evidence Report 5 High Performance Working: Developing a Survey Tool Evidence Report 6 Review of Employer Collective Measures: A Conceptual Review from a Public Policy Perspective Evidence Report 7 Review of Employer Collective Measures: Empirical Review Evidence Report 8 Review of Employer Collective Measures: Policy Review Evidence Report 9 Review of Employer Collective Measures: Policy Prioritisation Evidence Report 10 Review of Employer Collective Measures: Final Report Evidence Report 11 The Economic Value of Intermediate Vocational Education and Qualifications Evidence Report 12 UK Employment and Skills Almanac 2009 Evidence Report 13 National Employer Skills Survey 2009: Key Findings Evidence Report 14 Strategic Skills Needs in the Biomedical Sector: A Report for the National Strategic Skills Audit for England, 2010 Evidence Report 15 Strategic Skills Needs in the Financial Services Sector: A Report for the National Strategic Skills Audit for England, 2010 23 Evidence Report 16 Strategic Skills Needs in the Low carbon Energy generation Sector: A Report for the National Strategic Skills Audit for England, 2010 Evidence Report 17 Horizon Scanning and Scenario Building: Scenarios for Skills 2020 Evidence Report 18 High Performance Working: A Policy Review Evidence Report 19 High Performance Working: Employer Case Studies Evidence Report 20 A Theoretical Review of Skill Shortages and Skill Needs Evidence Report 21 High Performance Working: Case Studies Analytical Report Evidence Report 22 The Value of Skills: An Evidence Review Evidence Report 23 National Employer Skills Survey for England 2009: Main Report Evidence Report 24 Perspectives and Performance of Investors in People: A Literature Review Evidence Report 25 UK Employer Perspectives Survey 2010 Evidence Report 26 UK Employment and Skills Almanac 2010 Evidence Report 27 Exploring Employer Behaviour in relation to Investors in People Evidence Report 28 Investors in People - Research on the New Choices Approach Evidence Report 29 Defining and Measuring Training Activity Evidence Report 30 Product strategies, skills shortages and skill updating needs in England: New evidence from the National Employer Skills Survey, 2009 Evidence Report 31 Skills for Self-employment Evidence Report 32 The impact of student and migrant employment on opportunities for low skilled people Evidence Report 33 Rebalancing the Economy Sectorally and Spatially: An Evidence Review 24 Evidence Report 34 Maximising Employment and Skills in the Offshore Wind Supply Chain Evidence Report 35 The Role of Career Adaptability in Skills Supply Evidence Report 36 The Impact of Higher Education for Part-Time Students Evidence Report 37 International approaches to high performance working Evidence Report 38 The Role of Skills from Worklessness to Sustainable Employment with Progression Evidence Report 39 Skills and Economic Performance: The Impact of Intangible Assets on UK Productivity Growth Evidence Report 40 A Review of Occupational Regulation and its Impact Evidence Report 41 Working Futures 2010-2020 Evidence Report 42 International Approaches to the Development of Intermediate Level Skills and Apprenticeships Evidence Report 43 Engaging low skilled employees in workplace learning Evidence Report 44 Developing Occupational Skills Profiles for the UK Evidence Report 45 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2011: UK Results Evidence Report 46 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2011: England Results Evidence Report 47 Understanding Training Levies Evidence Report 48 Sector Skills Insights: Advanced Manufacturing Evidence Report 49 Sector Skills Insights: Digital and Creative Evidence Report 50 Sector Skills Insights: Construction Evidence Report 51 Sector Skills Insights: Energy 25 Evidence Report 52 Sector Skills Insights: Health and Social Care Evidence Report 53 Sector Skills Insights: Retail Evidence Report 54 Research to support the evaluation of Investors in People: Employer Survey Evidence Report 55 Sector Skills Insights: Tourism Evidence Report 56 Sector Skills Insights: Professional and Business Services Evidence Report 57 Sector Skills Insights: Education Evidence Report 58 Evaluation of Investors in People: Employer Case Studies Evidence Report 59 An Initial Formative Evaluation of Best Market Solutions Evidence Report 60 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2011: Northern Ireland National Report Evidence Report 61 UK Skill levels and international competitiveness Evidence Report 62 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2011: Wales Results Evidence Report 63 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2011: Technical Report Evidence Report 64 The UK Commission’s Employer Perspectives Survey 2012 Evidence Report 65 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2011: Scotland Results Evidence Report 66 Understanding Employer Networks Evidence Report 67 Understanding Occupational Regulation Evidence Report 68 Research to support the Evaluation of Investors in People: Employer Survey (Year 2) Evidence Report 69 Qualitative Evaluation of the Employer Investment Fund Phase 1 26 Evidence Report 70 Research to support the evaluation of Investors in People: employer case studies (Year 2) Evidence Report 71 High Performance Working in the Employer Skills Surveys Evidence Report 72 Training in Recession: The impact of the 2008-2009 recession on training at work Evidence Report 73 Technology and skills in the Digital Industries Evidence Report 74 Technology and skills in the Construction Industry Evidence Report 75 Secondary analysis of employer surveys: Urban/rural differences in access and barriers to jobs and training Evidence Report 76 Technology and Skills in the Aerospace and Automotive Industries Evidence Report 77 Supply of and demand for High-Level STEM skills Evidence Report 78 A Qualitative Evaluation of Demand-led Skills Solutions: Growth and Innovation Fund and Employer Investment Fund Evidence Report 79 A Qualitative Evaluation of Demand-led Skills Solutions: standards and frameworks Evidence Report 80 Forecasting the Benefits of the UK Commission’s Programme of Investments Evidence Report 81 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2013: UK Results Evidence Report 82 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2013: Technical Report Evidence Report 82 UK Commission’s Employer Skills Survey 2013: Technical Report Evidence Report 83 Working Futures 2012-2022 Evidence Report 84 The Future of Work: Jobs and skills in 2030 27 28 UKCES Renaissance House Adwick Park Wath-upon-Dearne Rotherham S63 5NB T +44 (0)1709 774 800 F +44 (0)1709 774 801 ISBN 978-1-908418-68-5 © UKCES 1st Ed/08.14 UKCES Sanctuary Buildings Great Smith St. Westminster London SW1P 3BT T +44 (0)20 7227 7800