FINAL REPORT SKILLS AND EMPLOYMENT COMMISSION September 2015

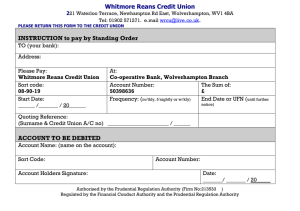

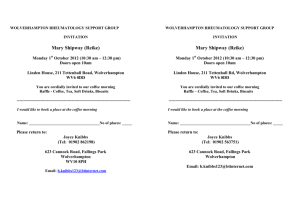

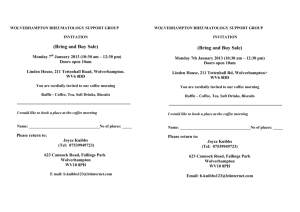

advertisement