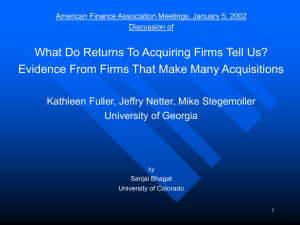

What Do Returns to Acquiring Firms Tell Us? Many Acquisitions

advertisement