Justice as a Dependent Variable: Subordinate Charisma as a Predictor... Interpersonal and Informational Justice Perceptions

advertisement

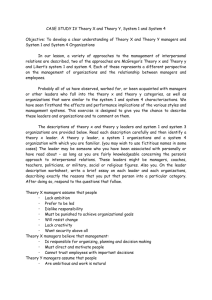

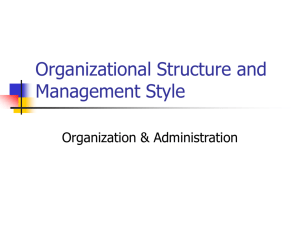

Journal of Applied Psychology 2007, Vol. 92, No. 6, 1597–1609 Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association 0021-9010/07/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1597 Justice as a Dependent Variable: Subordinate Charisma as a Predictor of Interpersonal and Informational Justice Perceptions Brent A. Scott Jason A. Colquitt and Cindy P. Zapata-Phelan Michigan State University University of Florida Research in the organizational justice literature has shown that interpersonal and informational justice are significant predictors of subordinate attitudes and behaviors. However, scholars have neglected to explore whether certain subordinate characteristics might be associated with managers’ adherence to interpersonal and informational justice rules. The current authors’ study tested a model, inspired by approach–avoidance perspectives (e.g., Gray, 1990), in which manager ratings of subordinate charisma influenced subordinate ratings of interpersonal and informational justice through the mechanisms of positive and negative sentiments (i.e., emotions felt by the manager toward the subordinate). A field study of 181 employees of a large national insurance company revealed partial support for this model. Structural equation modeling revealed that subordinate charisma was related to interpersonal justice perceptions, a relationship that was fully mediated by positive and negative sentiments. However, subordinate charisma was not associated with informational justice perceptions. These findings signal the potential utility in examining subordinate-based predictors of justice variables. Keywords: justice, affect, emotions, charisma Bies’s (2005) distinction between “exchanges” and “encounters.” According to Bies (2005), procedural and distributive justice are somewhat bounded in resource exchange contexts that may be relatively infrequent. In contrast, interpersonal and informational justice can be judged in virtually any encounter between managers and subordinates, regardless of whether resource allocation decisions are being made. This argument complements Folger’s (2001) suggestion that those justice forms are more within a manager’s discretion, providing managers with frequent opportunities to adhere to (or violate) those justice rules. Taken together, these arguments suggest that interpersonal and informational justice have “day-in day-out” significance that the other justice dimensions may not possess. Although scholars have gained an understanding of how interpersonal treatment is gauged and why it is so predictive of attitudes and behaviors, a critical gap remains unfilled in the literature. Specifically, do certain subordinate characteristics make it more or less likely that managers will adhere to the respect, propriety, justification, and truthfulness rules that compose interpersonal and informational justice? By and large, this question has remained unexamined because, as Korsgaard, Roberson, and Rymph (1998) observed, “To date, the justice literature has largely taken a onesided view of the dynamics of social exchange relationships, such as manager-subordinate dyads, by focusing on the manager’s role and neglecting the impact of the subordinate’s behavior on fair exchanges” (p. 741). This “one-sided view” is depicted graphically in Figure 1. Most studies in the justice literature view interpersonal and informational justice (and procedural and distributive justice) as exogenous variables that influence subordinate fairness perceptions and subordinate attitudinal and behavioral reactions. Much less attention is devoted to exploring why managers might adhere to justice rules in the first place, including whether subordinate characteristics might influence that tendency (see Colquitt & Greenberg, When subordinates talk about issues of justice or fairness, their accounts often deal with the interpersonal treatment they receive from their managers (Bies, 2001). In introducing the concept of interactional justice, Bies and Moag (1986) described four rules that have come to define fair interpersonal treatment on the part of managers: (a) respect—subordinates should be treated with sincerity and dignity, (b) propriety—managers should refrain from improper or prejudicial statements, (c) justification—managers should provide adequate explanations for decision making, and (d) truthfulness—those explanations should be honest, open, and candid. Current taxonomies of organizational justice group the respect and propriety rules under the interpersonal justice heading, with the justification and truthfulness rules defining informational justice (Bies, 2005; Colquitt, 2001; Colquitt & Shaw, 2005; Greenberg, 1993). Research on organizational justice has shown that the interpersonal and informational components of interactional justice are strong predictors of subordinates’ attitudes and behaviors (CohenCharash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, 2001). Indeed, sometimes those effects are stronger than the effects for procedural and distributive justice (Ambrose & Schminke, 2003; Aquino, Lewis, & Bradfield, 1999; Williams, Pitre, & Zainuba, 2002), which capture the fairness of decisionmaking processes and outcomes, respectively (Adams, 1965; Leventhal, 1976, 1980; Thibaut & Walker, 1975). The importance of interpersonal and informational justice can be explained with Brent A. Scott, Department of Management, Michigan State University; Jason A. Colquitt and Cindy P. Zapata-Phelan, Department of Management, University of Florida. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Brent A. Scott, Department of Management, N475 North Business Complex, East Lansing, MI 48824. E-mail: scott@bus.msu.edu 1597 1598 SCOTT, COLQUITT, AND ZAPATA-PHELAN Subordinate Perceptions of Justice Rule Adherence Interpersonal Justice Subordinate Characteristics ? Informational Justice Subordinate Fairness Perceptions Subordinate Attitudinal and Behavioral Reactions Procedural Justice Distributive Justice Figure 1. Framework characterizing existing research on organizational justice. 2003, for more discussion of this gap). From a theoretical standpoint, examining factors that influence justice rule adherence can provide a new direction for building models of fair treatment. An endogenous examination of justice rule adherence also may suggest that subordinates are not passive recipients of justice; rather, some subordinates may be more adept at shaping the way in which they are treated by their managers. From a practical standpoint, identifying factors that influence justice rule adherence could have a profound impact by helping to stop injustice before it starts. To date, the only study that has attempted to fill this gap was Korsgaard et al.’s (1998) investigation of the effects of subordinate assertive behaviors on managers’ informational justice. Assertive subordinates state their opinions in a straightforward manner, use posture and eye contact to display their confidence in those opinions, and ask follow-up questions to clarify their managers’ stance on decision events. Korsgaard et al. (1998) reasoned that those behaviors would promote more extensive justifications on the part of managers. That prediction was tested in two studies, one in the laboratory and one in the field. The laboratory study supported the linkage between subordinate assertiveness and informational justice. The field study, however, failed to support the linkage, though assertiveness was associated with higher levels of satisfaction and trust on the part of subordinates. Given these findings, it seems a worthy endeavor to identify other subordinate characteristics that could impact justice perceptions. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to identify a subordinate characteristic that could predict managers’ adherence to the rules of interpersonal and informational justice. A central premise that guided our choice of subordinate characteristic was that the day-in day-out discretionary nature of interpersonal and informa- tional justice could make adherence to those justice rules particularly sensitive to the affect that managers feel toward subordinates. Scholars in the affect literature have argued that many behaviors are governed by two primary motivational systems (Depue & Collins, 1999; Elliot & Thrash, 2002; Fowles, 1987; Gray, 1990). The approach system, which also is referred to as the behavioral activation system (BAS, e.g., Fowles, 1987) or the behavioral facilitation system (e.g., Depue & Collins, 1999), directs individuals toward experiences and stimuli that may yield pleasure and reward. In contrast, the avoidance system, which typically is referred to as the behavioral inhibition system (BIS, e.g., Fowles, 1987; Gray, 1990) directs individuals away from experiences and stimuli that they appraise as potentially noxious, threatening, or repulsing. As described more fully in the sections to follow, we propose that these approach and avoidance responses will prompt managers to adhere to interpersonal and informational justice rules more frequently when they feel more positively (and less negatively) toward subordinates. The critical question then becomes the following: What subordinate characteristics should promote more positive affect and less negative affect on the part of managers? One potential answer is charisma, as charismatic individuals have a personal magnetism that pulls others toward them through the arousal of positive feelings and emotions (Bass, 1985). Charismatic individuals are seen by others as “the ideal,” a view that affords such individuals an extraordinary level of influence over the behavior of others (House & Baetz, 1979; Weber, 1947; Yorges, Weiss, & Strickland, 1999). Accordingly, we propose that subordinate charisma is associated with managers’ adherence to interpersonal and informational jus- CHARISMA AND JUSTICE tice rules. We further propose that these relationships will be mediated by the affect felt by the manager toward the subordinate. According to Gray’s (1990) model, positive environmental signals (e.g., signals of reward) initiate the BAS and elicit corresponding positive emotions, which in turn motivate approach behavior. In contrast, negative environmental signals (e.g., signals of nonreward) initiate the BIS and elicit corresponding negative emotions, which in turn motivate avoidance behavior. Thus, the approach– avoidance perspective provides an integrative structure to our choice of variables. Specifically, a subordinate’s level of charisma serves as an environmental cue that triggers affect and activates the approach–avoidance system, which in turn influences adherence to interpersonal and informational justice. Subordinate Charisma The German sociologist Max Weber (1947) first discussed the relevance of charisma to leadership and organizations, defining it as a special gift possessed by few that results in extraordinary capability to influence. However, it was not until House’s (1977) publication of his theory of charismatic leadership that charisma became a popular topic of study in organizational behavior. Around this same time, Burns (1978) introduced the concept of transformational leadership, a process whereby leaders create strong connections with followers and influence them to transcend their self-interests to focus more on the long-term, intrinsic goals of the group. Charisma and transformational leadership were integrated when Bass (1985; see also Bass & Avolio, 1993) broke transformational leadership down into four dimensions: charisma (or idealized influence), inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Though not completely overlapping, as Judge and Piccolo (2004) noted, “it is clear that transformational leadership and charismatic leadership theories have much in common, and in important ways, each literature has contributed to the other” (p. 755). Since the publication of House’s (1977) theory, the concept of charisma has received significant attention in the leadership literature (e.g., Conger & Kanungo, 1998; Gardner & Avolio, 1998; House, Spangler, & Woycke, 1991; Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996; Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993; Shamir, Zakay, Breinin, & Popper, 1998). Importantly, researchers have suggested that charisma need not be limited to those in managerial positions. Bass (1990) argued that charismatic individuals “may be in high- or low-status positions” (p. 185), and Conger (1989) asserted that charisma “is not some magical ability limited to a handful” (p. 161). Such statements fit well with the notion that charisma is both a personal characteristic and a constellation of behaviors (Bass, 1985, 1990; Conger & Kanungo, 1998) and with meta-analytic findings that individuals residing at lower levels of the organization are just as (if not more) likely to be considered charismatic than are those at higher levels (Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Lowe, Kroeck, & Sivasubramaniam, 1996). Our study extends the concept of charisma to the organization’s lower levels by examining managers’ perceptions of subordinate charisma. Given that charisma is an attribution made by others (Conger & Kanungo, 1998) and is “in the eye of the beholder” (Bass, 1990, p. 193), it seems reasonable to expect that managers may perceive subordinates along a continuum of charisma—with some viewed as more charismatic than others. Although we ac- 1599 knowledge that some aspects of the construct, such as bringing about radical organizational change during times of crises, are not likely to be a part of charisma at the subordinate level, other aspects, such as being perceived by others as exceptional and ethical, displaying high levels of self-confidence, and emphasizing collective goals, may just as likely occur with subordinates as with managers. Indeed, as Lowe et al. (1996) noted, individuals at lower levels in the organization may have more opportunities to influence others via displays of charisma because such individuals interact with others more frequently. Subordinate Charisma and Managerial Sentiments According to Bass and Avolio’s (1993) conceptualization, the role of charisma is to enable the charismatic individual to impact the behavior of others through the formation of emotional bonds. Friedman, Prince, Riggio, and DiMatteo (1980) suggested that charisma is manifested in nonverbal emotional expressions such as displays of enthusiasm. Friedman, Riggio, and Casella (1988) supported this notion in a sample of undergraduate students, demonstrating that individuals who were rated as more charismatic were more emotionally expressive and consequently were able to enhance positive emotions in others and to reduce negative emotions. Although the role of feelings and emotions experienced toward the charismatic individual is an important component of theories of charismatic leadership (e.g., Bass & Avolio, 1993; Conger & Kanungo, 1998; Gardner & Avolio, 1998; House, 1977; Wasielewski, 1985), few studies have measured such feelings directly. If charismatic subordinates indeed are more emotionally expressive, how might this expressiveness affect others who interact with them? According to emotional contagion perspectives, individuals “catch” the emotions of others during encounters (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1994). Emotional contagion begins when the actor displays emotion in a blend of nonverbal displays such as facial expressions and body posture, in addition to verbal displays such as inflection of voice. Individuals interacting with the actor (i.e., target) subconsciously and automatically mimic those emotional displays, including the actor’s facial expressions (Dimberg, 1982; Lundqvist & Dimberg, 1995). The targets then receive internal feedback from their own mimicry, leading them to feel the same emotion that the actor is displaying (Tourangeau & Ellsworth, 1979). Given that people high in expressiveness tend to be especially adept at transferring their emotions to others (Sullins, 1989), this process should be stronger for charismatic actors (Cherulnik, Donley, Wiewel, & Miller, 2001; Friedman et al., 1980). Several studies have supported this emotional contagion hypothesis. For example, Pugh (2001) examined emotional contagion in a sample of bank tellers, finding that employees who were more emotionally expressive displayed positive emotions more frequently, which in turn led to increased positive affect in customers with whom they interacted. Barsade (2002), using a sample of undergraduates, found that group members’ emotions converged with a confederate trained to display either positive or negative emotions. More closely related to the current study, Cherulnik et al. (2001) reported that observers of undergraduate students trained to exhibit charismatic behaviors imitated those behaviors. In a second study, Cherulnik et al. (2001) found that undergraduates who watched televised presidential speeches converged emotion- 1600 SCOTT, COLQUITT, AND ZAPATA-PHELAN ally with each president’s displayed affect. Thus, existing evidence suggests that individuals do indeed “catch” the emotions of others. Although an emotional contagion perspective suggests that managers interacting with charismatic subordinates should experience positive emotions more frequently and negative emotions less frequently, such effects should be relatively short lived because emotions tend to be ephemeral in nature (Ekman & Davidson, 1994; Watson, 2000). Over time, however, those discrete emotional reactions should develop into particular sentiments felt toward the charismatic subordinate. Frijda (1994) defined sentiments as tendencies to respond affectively to particular persons or objects, referring to them as “likes” or “dislikes.” Similarly, Kelly and Barsade (2001) said sentiments are “valenced appraisals of an object and involve evaluation of whether something is liked or disliked” (p. 105). Sentiments are “distinctly social” (Stets, 2003, p. 309) and usually are organized around another person (Gordon, 1981). Sentiments and emotions are closely related; sentiments may arise from previous emotional encounters; and they are the bases for corresponding emotions during interactions with the person toward whom the sentiment is felt (Frijda, 1994). The primary difference lies in the duration of each: Emotions are more transitory, whereas sentiments are more stable. Drawing from Watson’s (2000) hierarchical structure of affect, we conceptualized positive sentiments as the elicitation of two particular positive emotions in managers during anticipated or actual interactions with subordinates: joviality and self-assurance. Joviality refers to feelings of happiness and enthusiasm, whereas self-assurance refers to feelings of pride and confidence (Watson & Clark, 1994). We chose these emotions because both represent positive affect (e.g., Watson & Tellegen, 1999) and because they tend to be highly correlated with each other (Watson, 2000). In addition, both emotions have inherent action tendencies relevant to justice rule adherence. Specifically, joviality and self-assurance motivate prosocial behaviors such as friendliness, sociability, and sharing of information (Isen, 1987; Lazarus, 1991). We conceptualized negative sentiments as the elicitation of two particular negative emotions in managers during anticipated or actual interactions with the subordinate: hostility and fear. Hostility refers to feelings of anger and disgust, whereas fear refers to feelings of nervousness and dread (Watson & Clark, 1994). Both emotions represent negative affect (e.g., Watson & Tellegen, 1999), and they also tend to be highly correlated with each other (Watson, 2000). In addition, both emotions have inherent action tendencies relevant to justice rule violation. Specifically, hostility and fear motivate antisocial behaviors, with hostility stimulating aggressive behavior and fear stimulating distancing and avoidance (Averill, 1983; Lazarus, 1991). Though the action tendencies of hostility and fear are somewhat different, Lazarus (1991) suggested that the two emotions are “interdependent sides of the same adaptational coin” in that both help individuals overcome situations appraised as threatening (p. 225). Managerial Sentiments and Adherence to Justice Rules If charismatic subordinates increase positive sentiments and decrease negative sentiments in others, how might those sentiments affect managerial justice rule adherence? The approach– avoidance models of behavior described in the opening of our article provide one potential answer (Depue & Collins, 1999; Elliot & Thrash, 2002; Fowles, 1987; Gray, 1990). According to these models, positive and negative feelings motivate behavior by activating the behavioral activation system (BAS) and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS), respectively. Activation of the BAS is associated with approach behavior, whereas activation of the BIS is associated with avoidance behavior. To the extent that interactions with charismatic subordinates generate positive feelings and suppress negative feelings in managers, managers should be motivated to approach and interact with charismatic subordinates more frequently than noncharismatic subordinates. That managers should be drawn to charismatic subordinates fits well with lay conceptualizations of charisma based on personal magnetism (American Heritage Dictionary, 2000) as well as with approach–avoidance perspectives of motivation (e.g., Gray, 1990). As noted at the outset, interpersonal justice is promoted when managers adhere to two particular justice rules: respect and propriety (Bies & Moag, 1986; Colquitt, 2001; Greenberg, 1993). If managers are motivated to approach subordinates toward whom they feel positively, managers will have more opportunities to interact with those subordinates in a respectful and courteous manner, and the positive sentiments accompanying managers’ approach motivations should facilitate adherence to interpersonal justice. On this point, research has shown that positive affective states are associated with more helpful, friendly, empathic, and sociable behaviors and fewer aggressive behaviors (George, 1991; Isen, 1987; Nezlek, Feist, Wilson, & Plesko, 2001). These tendencies suggest that positive sentiments will enhance respectful treatment and decrease improper treatment. In contrast, research has demonstrated that negative affect can inhibit adherence to norms of politeness (Tedeschi & Felson, 1994). It therefore follows that managers who feel negative sentiments toward subordinates will be more likely to violate the respect and propriety rules. Informational justice is promoted when managers adhere to two particular justice rules: justification and truthfulness (Bies & Moag, 1986; Colquitt, 2001; Greenberg, 1993). To the extent that managers are motivated to approach subordinates toward whom they hold positive sentiments, managers should gain more opportunities to share information. The positive sentiments accompanying managers’ approach motivations also should facilitate adherence to informational justice. This notion fits well with research on interpersonal attraction, which has demonstrated that individuals share more information with those to whom they are attracted (e.g., Collins & Miller, 1994). Likewise, research on psychological distancing has revealed that individuals attempt to avoid individuals who trigger negative emotions (Hess, 2000). Individuals can distance themselves from others in a variety of ways, including avoiding involvement, ignoring others, and engaging in deception (Goffman, 1961; Hess, 2000). Avoiding involvement and ignoring others likely would violate the justification rule of informational justice, whereas engaging in deception likely would violate the truthfulness rule of informational justice. Indeed, Folger and Skarlicki (2001) noted that distancing is a common explanation for the managerial tendency to withhold explanations when they should be offered. Thus, the avoidance response triggered by negative sentiments should create a distancing tendency which should prevent managers from fulfilling standards of informational justice. CHARISMA AND JUSTICE Summary In sum, we propose that, through the process of emotional contagion (Hatfield et al., 1994), managers will feel more positive sentiments and fewer negative sentiments toward charismatic subordinates compared with less charismatic subordinates. In turn, those sentiments should be associated with increased adherence to interpersonal and informational justice rules by activating approach versus avoidance motivational systems (e.g., Elliot & Thrash, 2002). Thus, positive and negative sentiments should mediate the relationships between subordinate charisma and interpersonal and informational justice perceptions. We therefore predicted the following: Hypothesis 1: Subordinate charisma is positively related to interpersonal and informational justice perceptions. Hypothesis 2: The relationships between subordinate charisma and interpersonal and informational justice perceptions are mediated by positive and negative sentiments. Method Participants Participants were 181 administrative employees of a large, national insurance company located in the Southeast. The average tenure in the participants’ current position was 2.14 years (SD ! 3.07), and they had worked for the organization for an average of 6.33 years (SD ! 7.07). Of the 181 participants, 125 (69%) were women, and 56 (31%) were men. The average age of the sample was 34.77 years (SD ! 11.29). Ethnicities were as follows: White (n ! 112), African American (n ! 39), Hispanic (n ! 10), Asian Pacific Islander (n ! 6), Native American (n ! 6), and other ethnicities (n ! 8). Procedure A human resources representative helped to recruit participants for the study. The contact person at the company advertised the study to employees via a brief e-mail composed by the authors. The e-mail described the study as an examination of job attitudes and instructed those who were interested in participating to come to a designated area outside of the employee lunchroom between the hours of 11:30 am and 1:00 pm on a specified date. The e-mail also stated that each participant’s immediate supervisor would be asked to complete a different survey. Finally, the e-mail told participants they would receive $20 for taking part in the study. One of the study’s authors distributed questionnaires with the assistance of the contact person. Subordinates completed a survey that assessed their perceptions of their managers’ adherence to interpersonal, informational, procedural, and distributive justice rules. Although no hypotheses were devoted to procedural and distributive justice because these justice dimensions are more exchange based than encounter based (Bies, 2005), we felt it was important to include all four dimensions. Justice scholars have emphasized the need to assess all justice dimensions, even when the focus is only on a subset, so that the results can be as informative as possible (Bies, 2005; Colquitt et al., 2001; Colquitt & Greenberg, 2003). Managers were then given a separate survey 1601 to complete that assessed their perceptions of the subordinate’s charisma and the positive and negative sentiments they felt when interacting with the subordinate. We chose to use manager reports to assess subordinate charisma because the leadership literature emphasizes that charisma is an attribution made by others (Bass, 1990; Conger & Kanungo, 1998). Thus, a subordinate’s self-reported charisma might not capture the concept in a construct-valid manner. We chose to use subordinate reports to assess managers’ adherence to justice rules for two reasons. First, this strategy allowed us to remove samesource bias from the tests of our primary hypotheses. Second, this strategy matches the typical operationalization in the justice literature, in which subordinate perceptions are used to conceptualize the justice dimensions (Colquitt, 2001; Colquitt & Shaw, 2005; Moorman, 1991). To match each subordinate’s survey with his or her corresponding manager’s survey, we numbered both surveys and the postage-paid envelopes in which they were returned. In all, we obtained completed, matched data for 132 manager– subordinate dyads, for an overall response rate of 72.9%. Measures Organizational justice. We measured subordinates’ perceptions of their managers’ adherence to interpersonal, informational, procedural, and distributive justice rules with the scales developed and validated by Colquitt (2001). Subordinates indicated the extent to which they agreed with each statement by using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (to a very small extent) to 5 (to a very large extent). For interpersonal justice, subordinates were referred to the interpersonal treatment received from their managers. The items assessed adherence to Bies and Moag’s (1986) respect and propriety rules (see also Greenberg, 1993). Sample items from the four-item scale included “Does your supervisor treat you in a polite manner?” “Does your supervisor treat you with dignity?” and “Does your supervisor refrain from improper remarks or comments?” The coefficient alpha for this scale was .93. For informational justice, subordinates were referred to the explanations given by managers for decision events. The items assessed adherence to Bies and Moag’s (1986) justification and truthfulness rules (see also Greenberg, 1993). Sample items for the five-item scale included “Is your supervisor candid in communications with you?” “Does your supervisor explain decision procedures thoroughly?” and “Does your supervisor communicate details in a timely manner?” The coefficient alpha for this scale was .91. For procedural justice, subordinates were referred to the procedures their managers use to make decisions about pay evaluations, promotions, rewards, and so on. The items assessed adherence to Leventhal’s (1980) and Thibaut and Walker’s (1975) justice rules. Sample items from the seven-item scale included “Are those procedures applied consistently?” “Are those procedures free of bias?” and “Are you able to express your views and feelings during those procedures?” The coefficient alpha for this scale was .85. For distributive justice, subordinates were referred to the outcomes they receive from their jobs, such as pay, evaluations, promotions, rewards, and so on. The items assessed adherence to an equity rule for allocating outcomes as opposed to an equality or need rule (Adams, 1965; Leventhal, 1976). Sample items from the four-item scale included “Do those outcomes reflect the effort you have put into your work?” “Are those outcomes justified, given your per- 1602 SCOTT, COLQUITT, AND ZAPATA-PHELAN formance?” and “Do those outcomes reflect what you have contributed to your work?” The coefficient alpha for this scale was .96. Charisma. We measured managers’ perceptions of subordinate charisma by using the Charisma (or Idealized Influence) scale from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Avolio & Bass, 2004). This scale assesses attributes and behaviors on the part of a focal person that can create a sense of admiration and respect. All items used a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The seven items assessed the extent to which subordinates emphasized their values, made ethical decisions, and possessed a sense of confidence and purpose. We omitted one item from the scale that assessed the extent to which subordinates instill pride in the manager, given the conceptual overlap between that item and our positive sentiments measure. The coefficient alpha for this scale was .88. Positive and negative sentiments. We measured managers’ positive sentiments felt toward subordinates by using a four-item scale that tapped two of the positive emotions included in the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded form (PANAS–X; Watson & Clark, 1994): joviality and self-assurance. Sample items included “Being around this employee makes me feel happy” and “This employee often makes me feel proud.” The coefficient alpha for positive sentiments was .83. We measured managers’ negative sentiments felt toward subordinates by using a four-item scale that tapped two of the negative emotions included in the PANAS–X (Watson & Clark, 1994): hostility and fear. Sample items included “This employee often makes me feel angry” and “At times, this employee makes me feel nervous.” The coefficient alpha for negative sentiments was .70. Analysis In testing our hypotheses, we controlled for demographic similarity given that past research has shown that individuals feel more positive sentiments toward others who share their demographic profile (Tsui & O’Reilly, 1989). We controlled for two specific forms of demographic similarity: gender similarity and age similarity. Gender similarity was operationalized by using a dummy variable with 1 coded as similar and 0 coded as dissimilar. Fifty-eight percent of our participants worked in same-gender dyads. Age similarity was operationalized as the absolute difference between the supervisors’ and subordinates’ ages. On average, the members of the supervisor–subordinate dyads in our sample differed by 11 years of age. We also controlled for subordinate Neuroticism to partial out affect-driven response tendencies that could bias perceptions of interpersonal and informational justice. Neuroticism was assessed with the Big Five Inventory (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991). The coefficient alpha for Neuroticism was .81. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to provide some support for the construct validity of our scale measures. The hypothesized 7-factor measurement model was tested by entering the covariance matrix of the items into LISREL 8.52 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996). Fit statistics indicated acceptable fit for the hypothesized model and were as follows: "2(712, N ! 124) ! 1,166.18, p # .001, "2/df ! 1.64, incremental fit index (IFI) ! .91, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) ! .072. Acceptable model fit typically is inferred when IFI is above .90, RMSEA is .08 or lower, and the ratio of chi square to degrees of freedom is below 3 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Kline, 2005). All 35 factor loadings were statistically significant and averaged as follows: Interpersonal Justice (.92), Informational Justice (.86), Procedural Justice (.73), Distributive Justice (.96), Charisma (.77), Positive Sentiments (.81), Negative Sentiments (.76), and Neuroticism (.72). The 7-factor measurement model fit the data significantly better than did alternative measurement models as judged by a chi-square difference test. Those alternative measurement models included a model that combined interpersonal and informational justice into one Interactional Justice factor, "2diff(7, N ! 124) ! 447.38, p # .001; a model that combined positive and negative sentiments into one Sentiments factor, "2diff(7, N ! 124) ! 120.11, p # .001; and a model that combined positive sentiments and charisma into one Positive Perceptions factor, "2diff(7, N ! 124) ! 46.38, p # .001. We should note that a total of 78 managers assessed charisma and sentiments for the 132 subordinates in the final sample. Thus, some managers completed a survey for more than 1 subordinate. Specifically, 24 of the 78 managers completed multiple subordinate assessments, with an average of 3.3 subordinates being rated by those 24 managers. We therefore computed intraclass correlations (ICCs) to verify that the subordinate level of analysis was appropriate for the indicators used in our analyses. The average ICC(1) values were as follows: .04 for subordinate Charisma, .19 for Positive Sentiments, .29 for Negative Sentiments, .13 for Interpersonal Justice, and .10 for Informational Justice. Bliese and Hanges (2004) noted that, when examining relationships among variables at the same level of analysis (e.g., the individual level), failing to account for nonindependence can harm statistical power when traditional analyses are used rather than random coefficient modeling. The authors offered a table for gauging the loss in power as the ICC(1) for the dependent variable rises (see Bliese & Hanges, 2004, Table 1, p. 412). Their table reveals a 5% drop in power for tests of interpersonal and informational justice effects (with power levels of .861 for random coefficient modeling and .816 for traditional approaches) and a 10% drop in power for tests of positive and negative sentiments (with power levels of .846 and .744, respectively). Given these relatively modest differences in power, we elected to utilize the traditional form of structural equation modeling that should be more familiar to most readers. Results Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among the variables used in the study, with coefficient alphas presented on the diagonal. Most notable are the correlations between subordinate charisma and the organizational justice dimensions. Subordinate charisma was positively correlated with interpersonal justice but not informational justice. Although not the focus of our hypotheses, subordinate charisma also was positively correlated with procedural justice and (to a lesser extent) distributive justice. We return to these latter relationships in the Discussion section. Tests of Hypotheses Our structural equation modeling analyses were performed with LISREL 8.52, with the measurement model results reviewed above 1603 CHARISMA AND JUSTICE Table 1 Descriptive Statistics, Correlations, and Reliabilities Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Subordinate charisma Positive sentiments Negative sentiments Interpersonal justice Informational justice Procedural justice Distributive justice Gender similarity Age similarity Neuroticism M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3.57 3.89 1.98 4.65 4.13 3.51 3.53 0.58 11.04 2.54 0.63 0.64 0.72 0.52 0.78 0.70 1.06 0.50 7.95 0.82 (.88) .70* &.34* .25* .06 .31* .17* .07 &.12 .10 (.82) &.54* .36* .07 .30* .16 .09 .05 &.03 (.70) &.28* &.02 &.16 &.01 &.12 &.01 &.02 (.90) .50* .32* .40* &.08 &.07 &.10 (.90) .55* .49* &.16 &.10 &.16 (.85) .62* &.13 &.09 &.17 (.96) &.19* &.03 &.13 — &.04 .03 — .12 (.81) Note. n ! 124 after listwise deletion of missing data. Coefficient alphas are presented along the diagonal in parentheses (where applicable). p # .05. * supplemented by the structural paths used to test our predictions. Control variables were included by adding direct paths from gender similarity, age similarity, and Neuroticism to interpersonal and informational justice. In general, gender similarity was associated with lower perceptions of interpersonal and informational justice, as was subordinate Neuroticism (the effects of age similarity were nonsignificant). We contrasted two a priori structural models: one in which the relationships between subordinate charisma and interpersonal and informational justice perceptions were fully mediated by positive and negative sentiments and one in which mediation was only partial. The results of those two structural models are shown in Figure 2, where the path coefficients represent unstandardized regression weights. Both models provided an acceptable fit to the data, and the fit of the models was not significantly different, "2diff(2, N ! 124) ! 0.67, ns. Hypothesis 1 predicted that subordinate charisma is positively related to interpersonal and informational justice perceptions. Figure 2 provides LISREL’s effect decomposition for both structural models. The total effect of subordinate charisma on interpersonal justice was a statistically significant .37, providing support for our prediction. That total effect can be recovered by tracing the combination of paths that connect the two variables (for example, in the top panel, [.84 $ .32] % [–.41 $ –.27] ! .37). Unexpectedly, the total effect of subordinate charisma on informational justice was a nonsignificant .16, failing to support our prediction. Thus Hypothesis 1 received partial support. Hypothesis 2 predicted that the relationships between subordinate charisma and interpersonal and informational justice are mediated by positive and negative sentiments. The informational justice part of that prediction was not supported given that the total effect for charisma on informational justice was nonsignificant, leaving no effect to be mediated. With respect to interpersonal justice, the adequate fit of both models in Figure 2 provides some support for the prediction, with the equivalent fit for the more parsimonious model in the top panel providing evidence of complete mediation for charisma and interpersonal justice. The results in the top panel reveal that subordinate charisma was significantly related to both positive sentiments (B ! .84) and negative sentiments (B ! –.41). Both sentiments were, in turn, related to interpersonal justice (B ! .32 for positive sentiments; B ! –.27 for negative sentiments). The output in the bottom panel provides the information needed to test mediation from a variety of perspectives. MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002) reviewed a number of complementary approaches to testing mediation. Among them was the “causal steps” approach popularized by Baron and Kenny (1986). This approach first requires demonstrating that the independent variable has significant effects on the mediator(s) and that the mediator(s) have significant effects on the dependent variable. The results in Figure 2 support both steps for interpersonal justice. The causal steps approach then requires that the total effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable be decreased when controlling for the mediator. In Figure 2, that step represents the difference between the .37 total effect and the –.03 direct effect, which is statistically significant. Although the causal steps approach supports mediation, MacKinnon et al. (2002) noted that it often suffers from low statistical power. They therefore recommended that alternative approaches be utilized, such as the “product of coefficients” approach popularized by Sobel (1982). From this perspective, a statistically significant indirect effect (when a direct effect also is modeled) supports mediation. The bottom panel of Figure 2 reveals that the indirect effect of charisma on interpersonal justice was a statistically significant .40. Hypothesis 2 therefore received partial support. Discussion This study explored a critical question that largely has been neglected in the justice literature; namely, are certain subordinate characteristics associated with managers’ adherence to justice rules? To address this question, we drew from approach–avoidance perspectives of behavior (e.g., Gray, 1990) to test a model linking subordinate charisma to interpersonal and informational justice perceptions through the underlying mechanisms of positive and negative sentiments. In doing so, we were able to elucidate the process by which subordinate charisma affects justice rule adherence. Our results demonstrated that subordinate charisma was positively associated with interpersonal justice and that this effect was mediated by increased positive and decreased negative sentiments felt by managers toward their subordinates. Interestingly, alternative model comparisons pitting a fully mediated model against a partially mediated model favored the former, suggesting that positive and negative sentiments were completely responsible for the relationship between subordinate charisma and interpersonal justice. In addition, both positive and negative sentiments exhibited significant, unique effects on interpersonal justice. It 1604 SCOTT, COLQUITT, AND ZAPATA-PHELAN Interpersonal Effect Decomposition: Total Effect = .37* Indirect Effect = .37* Direct Effect = na .32* Positive Sentiments Interpersonal Justice 5.22* .07 .84* 5.19* Gender Similarity 5.02 Subordinate Charisma Age Similarity 5.07 5.23* 5.41* Neuroticism 5.27* Negative Sentiments 5.15 5.21* Informational Justice Informational Effect Decomposition: Total Effect = .16 Indirect Effect = .16 Direct Effect = na X2 (793, N = 124) = 1,291.65; X2 /df = 1.63; IFI = .90; RMSEA = .072 Interpersonal Effect Decomposition: Total Effect = .37* Indirect Effect = .40* Direct Effect = -.03 .35* Positive Sentiments Interpersonal Justice 5.03 Subordinate Charisma 5.22* Gender Similarity 5.08 .85* 5.19* 5.03 Age Similarity .17 5.05 5.24* 5.41* Neuroticism 5.27* Negative Sentiments 5.15 Informational Justice 5.23* Informational Effect Decomposition: Total Effect = .16 Indirect Effect = 5.01 Direct Effect = .17 X2 (791, N = 124) = 1,292.32; X2 /df = 1.63; IFI = .90; RMSEA = .072 Figure 2. Structural equation modeling results to test hypotheses. Values shown in the figures are unstandardized regression coefficients. Procedural and distributive justice were included in the analyses but paths to them were fixed to zero. IFI ! incremental fit index; RMSEA ! root-mean-square error of approximation. *p # .05, one-tailed. CHARISMA AND JUSTICE may be that positive sentiments shape interpersonal justice by triggering more respectful and courteous treatment but that negative sentiments also have an impact by enhancing the frequency of improper or prejudicial statements. In contrast to the results for interpersonal justice, the results for informational justice were not supported. Subordinate charisma was not related to informational justice, and informational justice was not correlated with either positive or negative sentiments. These null results could be attributed to two possibilities. First, it may be that informational justice is not as “encounter based” as interpersonal justice. Recall that Bies (2005) argued that both interactional justice components held a special importance in organizations because they could be judged on a day-in day-out basis in virtually any subordinate–manager encounter. We had reasoned that both interpersonal and informational justice would be particularly sensitive to subordinate charisma and managerial sentiments for that reason. However, it could be that informational justice, like distributive and procedural justice, is more “exchange based.” After all, informational justice relies on adhering to rules of justification and truthfulness during decision-making events. Those rules seem to require some sort of exchange context so that there is something for the manager to explain to subordinates. Alternatively, it could be that informational justice can be evaluated relatively frequently but that managers are unwilling to share negative information with charismatic subordinates. In other words, managers may have approached charismatic subordinates more frequently than noncharismatic subordinates but, in an effort to protect charismatic subordinates from potentially negative information, may have withheld certain details. Indeed, the criteria for informational justice do not stipulate that the information provided has to be positively valenced; instead, informational justice is fostered when any type of information is provided, either positive or negative, so long as that information is adequate and candid (Bies & Moag, 1986). Thus, managers may have offered charismatic subordinates more frequent justifications but also less candid ones, resulting in a nonsignificant relationship between subordinate charisma and informational justice perceptions. Taken together, our findings contribute to the literature on organizational justice in three important ways. First, our results extend the findings of Korsgaard et al. (1998) by identifying an additional subordinate characteristic, charisma, that is associated with managers’ adherence to justice rules. Second, this study answers calls in the literature to focus on the subordinate side of the justice equation (Colquitt & Greenberg, 2003; Korsgaard et al., 1998). As illustrated in Figure 1, the literature has tended to view subordinates merely as passive recipients of just or unjust treatment, neglecting the possibility that subordinate characteristics can actually influence justice rule adherence. Our results, coupled with those of Korsgaard et al. (1998), suggest that just treatment is not a completely one-sided affair; rather, both managers and subordinates may shape justice in the workplace. Third, our findings further support the distinction between interpersonal and informational justice by demonstrating that the two forms of justice, which once were subsumed by interactional justice (Bies & Moag, 1986), are uniquely related to subordinate charisma and positive and negative sentiments. Such findings are in accordance with previous studies supporting the separation of interpersonal and informational justice (e.g., Colquitt, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001). 1605 Suggestions for Future Research Our results offer a number of suggestions for future research. First and foremost, we hope that this study will spur additional theorizing and research on subordinate characteristics that are associated with managers’ adherence to justice rules. Our results suggest that subordinate characteristics that are associated with positive and negative sentiments could influence adherence to interpersonal justice rules. One promising subordinate characteristic for future research may be self-monitoring, which reflects a tendency to observe, regulate, and control one’s public appearance of self when interacting in social settings (Day & Kilduff, 2003; Snyder, 1974). High self-monitors tend to prioritize enhancing their status in an organization and often attain more desirable positions in social networks. Those tendencies may serve as assets that encourage their managers to adhere to norms of interpersonal treatment. As research expands to consider other subordinate-based predictors of justice rule adherence, it may be particularly important to focus on informational justice. Because informational justice was unrelated to subordinate charisma or managerial sentiments in our study, it remains an open question what subordinate characteristics could affect managers’ adherence to the justification and truthfulness rules. One possibility is feedback seeking, a construct that summarizes the frequency with which subordinates seek feedback, the methods they use to seek that feedback, and the topics about which they seek feedback (Ashford, Blatt, & VandeWalle, 2003; Ashford & Cummings, 1983). As with self-monitoring, feedback seeking occurs partly as a means of enhancing one’s status. It follows that individuals with strong feedback-seeking tendencies should be more likely to seek out justifications for key decisions, particularly when those decisions have some impact on their standing in the organization. In addition, there also may be value in examining subordinate characteristics that are associated with managers’ adherence to procedural justice rules. Although we included procedural justice in our data collection in the interest of completeness, we made no hypotheses for it because it is bounded in relatively infrequent exchange contexts and is somewhat dependent on formalized systems in addition to managerial decision-making styles. Unexpectedly, subordinate charisma was positively correlated with procedural justice perceptions. To explore this finding more fully, we examined a structural equation model with procedural justice as the outcome rather than interpersonal and informational justice by using the structure in the bottom panel of Figure 2. Tests of mediation revealed that the total effect of subordinate charisma on procedural justice was .47, that the indirect effect was near zero (–.05), and that the direct effect matched the total effect (.52). These results suggest that subordinate charisma did predict procedural justice perceptions but that the relationship was in no way mediated by sentiments. Although we found that sentiments mediated the relationship between subordinate charisma and interpersonal justice, it may be that less affective mechanisms explain the association with procedural justice. If we might speculate about other potential mediators, two mechanisms seem likely. First, it may be that the morality component of charisma prompts managers to themselves behave more morally, resulting in greater adherence to Leventhal’s (1980) bias suppression and ethicality rules of procedural justice. In this 1606 SCOTT, COLQUITT, AND ZAPATA-PHELAN case, charismatic subordinates may motivate their managers to become better leaders in their own right, thus increasing perceptions of justice. Second, it may be that the enhanced influence enjoyed by charismatic subordinates results in higher levels of voice and input, thereby enhancing procedural justice perceptions (Folger, 1977; Shapiro & Brett, 2005; Thibaut & Walker, 1975). Finally, future research should explore contextual factors that may qualify the results shown in our study. Our predictions for interpersonal and informational justice were grounded in approach versus avoidance motivational systems (e.g., Elliot & Thrash, 2002). Although our interpretation of positive sentiments facilitating approach behavior and negative sentiments facilitating avoidance behavior is consistent with those models, managers also may approach or avoid subordinates due to contextual factors. For example, approach behaviors may be more likely in instances of high task or resource interdependence (Wageman, 2001). Likewise, managers may approach subordinates who are central in their network more frequently than they approach subordinates on the periphery of the network (e.g., Brass & Burkhardt, 1993). In these cases, increased adherence to interpersonal and informational justice rules may not necessarily result because the approach behavior is driven by reasons other than affect. Nevertheless, future research could examine whether approach–avoidance behaviors not driven by affect could be associated with adherence to justice rules. Limitations Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, we measured subordinates’ perceptions of managers’ justice rule adherence rather than actual rule adherence. Though it is customary in the justice literature to assess justice from the subordinate’s perspective, this method leaves open the possibility that charismatic subordinates merely perceived higher levels of rule adherence regardless of their managers’ actual behaviors, perhaps because charismatics have a more positive lens through which they interpret their environment. However, the charisma relationships remained significant with subordinate Neuroticism controlled, suggesting that our results are not an artifact of response tendencies. Second, our measures of positive and negative sentiments did not sample all potential positive and negative emotions that may be associated with subordinates. For example, we operationalized positive sentiments as the elicitation of joviality and self-assurance in managers during real or anticipated encounters with the focal subordinate, consistent with Frijda’s (1994) conceptualization of sentiments. Though we drew from Watson’s (2000) hierarchical structure of affect in choosing these emotions, we did not include positive emotions such as attentiveness, which refers to feelings of alertness and concentration. Likewise, though we operationalized negative sentiments as the elicitation of hostility and fear, we omitted other negative emotions in Watson’s (2000) structure of affect, such as guilt. Future researchers should consider other emotions in addition to those examined in the current study to determine whether our results generalize or whether new findings emerge. We also should note that the internal consistency estimate for our negative sentiments scale was marginal at .70. Future research should include a more extensive set of negative emotions in an effort to boost reliability levels. Third, the statistical power of our structural equation models may have been hindered to some degree by the nonindependence created by having 24 managers complete assessments for multiple subordinates. In general, however, the differences in statistical power between traditional structural equation modeling and alternatives such as random coefficient modeling should be modest given the ICC(1) values in our data (Bliese & Hanges, 2004). Moreover, the effect sizes for our statistically significant results were quite strong, and the effect sizes for our nonsignificant results were often near zero, making issues of power less critical (Bliese & Hanges, 2004). Still, future researchers interested solely in individual-level effects should attempt to ensure that their respondents are independent from one another whenever possible. Finally, we failed to assess subordinates’ job performance when testing the relationships between subordinate charisma and interpersonal and informational justice. Some facets of the charisma construct are relevant to performance in many jobs, including the projection of confidence and the ability to influence others. It therefore remains an empirical question whether the charisma effects observed in our data would remain as strong with performance controlled. We would note, however, that Colquitt et al.’s (2001) meta-analysis of the organizational justice literature failed to yield significant relationships between interpersonal justice and performance (r ! .03) or between informational justice and performance (r ! .13). Although the few studies that have investigated those relationships conceptualized the causal order as flowing from justice to performance, those studies are typically crosssectional and correlational in nature. The lack of significant covariation between interpersonal and informational justice and job performance provides some support for the belief that our charisma effects are not an artifact of differences in performance levels across subordinates. Practical Implications Despite these limitations, our results offer practical implications for both subordinates and managers. If future research replicates the effects observed in our data, then subordinates may benefit from an awareness that they are not merely passive recipients of just or unjust treatment. Rather, they may be able to proactively manage the treatment they receive by acting more charismatically. Although some subordinates naturally may be more charismatic, perhaps because they possess personality traits that encourage such behaviors (Judge & Bono, 2000), past research has shown that individuals can be trained to become more charismatic (Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996; Towler, 2003). For example, Towler’s (2003) training in charismatic style and visionary content was associated with increased charismatic behaviors, such as the use of analogies, stories, body gestures, and an animated tone of voice. Such training could be built into employee development courses to provide a means of improving subordinates’ skills in this area. Those efforts could also be bolstered by adding charismatic content into the annual assessments that help guide employee development efforts. From the manager’s perspective, it is important for managers to understand the factors that may intentionally (or unintentionally) impact their adherence to interpersonal justice rules. We suspect that many managers would be surprised that their own sentiments, influenced by subordinate characteristics, were associated with perceptions of interpersonal treatment. Being sensitized to the effects of subordinate characteristics could help managers resist CHARISMA AND JUSTICE the temptation to act disrespectfully toward subordinates who trigger negative feelings within them. Scholars often have recommended justice training as a means of emphasizing the importance of justice rule adherence to managers (Skarlicki & Latham, 2005). Our results could be incorporated into such training programs to emphasize that leaders may find it more difficult to transfer their training to particular subordinates. References Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–299). New York: Academic Press. Ambrose, M. L., & Schminke, M. (2003). Organization structure as a moderator of the relationship between procedural justice, interactional justice, perceived organizational support, and supervisory trust. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 295–305. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). (2000). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Aquino, K., Lewis, M. U., & Bradfield, M. (1999). Justice constructs, negative affectivity, and employee deviance: A proposed model and empirical test. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 1073–1091. Ashford, S. J., Blatt, R., & VandeWalle, D. (2003). Reflections on the looking glass: A review of research on feedback-seeking behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 29, 773–799. Ashford, S. J., & Cummings, L. L. (1983). Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 32, 370 –398. Averill, J. R. (1983). Studies on anger and aggression: Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist, 38, 1145–1160. Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2004). Multifactor leadership questionnaire: Third edition manual and sampler set. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden. Barling, J., Weber, T., & Kelloway, E. K. (1996). Effects of transformational leadership training on attitudinal and financial outcomes: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 827– 832. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. Barsade, S. G. (2002). The ripple effects: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644 – 675. Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press. Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership: A response to critiques. In M. M. Chemers & R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions (pp. 49 – 80). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Bies, R. J. (2001). Interactional (in)justice: The sacred and the profane. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 89 –118). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Bies, R. J. (2005). Are procedural and interactional justice conceptually distinct? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), The handbook of organizational justice (pp. 85–112). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. F. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negotiations in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43–55). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Bliese, P. D., & Hanges, P. J. (2004). Being both too liberal and too conservative: The perils of treating grouped data as though they were independent. Organizational Research Methods, 7, 400 – 417. Brass, D. J., & Burkhardt, M. E. (1993). Potential power and power use: 1607 An investigation of structure and behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 441– 470. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136 –162). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row. Cherulnik, P. D., Donley, K. A., Wiewel, T. S. R., & Miller, S. R. (2001). Charisma is contagious: The effect of leaders’ charisma on observers’ affect. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 2149 –2159. Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 278 –321. Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 457– 475. Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 386 – 400. Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425– 445. Colquitt, J. A., & Greenberg, J. (2003). Organizational justice: A fair assessment of the state of the literature. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 165–210). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Colquitt, J. A., & Shaw, J. C. (2005). How should organizational justice be measured? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), The handbook of organizational justice (pp. 3–56). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Conger, J. A. (1989). The charismatic leader: Behind the mystique of exceptional leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1998). Charismatic leadership in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Day, D. V., & Kilduff, M. (2003). Self-monitoring personality and work relationships: Individual differences in social networks. In M. R. Barrick & A. M. Ryan (Eds.), Personality and work: Reconsidering the role of personality in organizations (pp. 205–228). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Depue, R. A., & Collins, P. F. (1999). Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine facilitation of incentive motivation and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 491–569. Dimberg, U. (1982). Facial reactions to facial expressions. Psychophysiology, 26, 643– 647. Ekman, P., & Davidson, R. J. (1994). The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. New York: Oxford University Press. Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach–avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 804 – 818. Folger, R. (1977). Distributive and procedural justice: Combined impact of “voice” and improvement on experienced inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 108 –119. Folger, R. (2001). Fairness as deonance. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Theoretical and cultural perspectives on organizational justice (pp. 3–34). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Folger, R., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2001). Fairness as a dependent variable: Why tough times can lead to bad management. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: From theory to practice (pp. 97–118). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Fowles, D. C. (1987). Application of a behavioral theory of motivation to the concepts of anxiety and impulsivity. Journal of Research in Personality, 21, 417– 435. Friedman, H. S., Prince, L. M., Riggio, R. E., & DiMatteo, M. R. (1980). Understanding and assessing nonverbal expressiveness: The affective communication test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 333–351. 1608 SCOTT, COLQUITT, AND ZAPATA-PHELAN Friedman, H. S., Riggio, R. E., & Casella, D. F. (1988). Nonverbal skill, personal charisma, and initial attraction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 203–211. Frijda, N. H. (1994). Varieties of affect: Emotions and episodes, moods, and sentiments. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion (pp. 59 – 67). New York: Oxford University Press. Gardner, W. L., & Avolio, B. J. (1998). The charismatic relationship: A dramaturgical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23, 32–58. George, J. M. (1991). State or trait: Effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 299 –307. Goffman, E. (1961). Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill. Gordon, S. L. (1981). The sociology of sentiments and emotion. In M. Rosenberg & R. H. Turner (Eds.), Social psychology: Sociological perspectives (pp. 562–592). New York: Basic Books. Gray, J. A. (1990). Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition and Emotion, 4, 269 –288. Greenberg, J. (1993). The social side of fairness: Interpersonal and informational classes of organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: Approaching fairness in human resource management (pp. 79 –103). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional contagion. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hess, J. A. (2000). Maintaining nonvoluntary relationships with disliked partners: An investigation into the use of distancing behaviors. Human Communication Research, 26, 458 – 488. House, R. J. (1977). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership: The cutting edge (pp. 189 –207). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. House, R. J., & Baetz, M. L. (1979). Leadership: Some empirical generalizations and new research directions. In B. M. Staw (Ed.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 341– 423). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. House, R. J., Spangler, W. D., & Woycke, J. (1991). Personality and charisma in the U.S. presidency: A psychological theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 364 –396. Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 203–253). New York: Academic Press. John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory–Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International. Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2000). Five-factor model of personality and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 751– 765. Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 755–768. Kelly, J. R., & Barsade, S. G. (2001). Mood and emotions in small groups and work teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 99 –130. Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1996). Direct and indirect effects of three core charismatic leadership components on performance and attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 36 –51. Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press. Korsgaard, M. A., Roberson, L., & Rymph, R. D. (1998). What motivates fairness? The role of subordinate assertive behavior on managers’ interactional fairness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 731–744. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press. Leventhal, G. S. (1976). The distribution of rewards and resources in groups and organizations. In L. Berkowitz & W. Walster (Eds.), Ad- vances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 91–131). New York: Academic Press. Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. Gergen, M. Greenberg, & R. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). New York: Plenum Press. Lowe, K. B., Kroeck, K. G., & Sivasubramaniam, N. (1996). Effectiveness correlates of transformation and transactional leadership: A metaanalytic review of the MLQ literature. Leadership Quarterly, 7, 385– 425. Lundqvist, L. O., & Dimberg, U. (1995). Facial expressions are contagious. Journal of Psychophysiology, 9, 203–211. MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. Moorman, R. H. (1991). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 845– 855. Nezlek, J. B., Feist, G. J., Wilson, C. F., & Plesko, R. M. (2001). Day-to-day variability in empathy as a function of daily events and mood. Journal of Research in Personality, 35, 401– 423. Pugh, S. D. (2001). Service with a smile: Emotional contagion in the service encounter. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 1018 –1027. Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4, 577–594. Shamir, B., Zakay, E., Breinin, E., & Popper, M. (1998). Correlates of charismatic leader behavior in military units: Subordinates’ attitudes, unit characteristics, and superiors’ appraisals of leader performance. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 387– 409. Shapiro, D. L., & Brett, J. M. (2005). What is the role of control in organizational justice? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), The handbook of organizational justice (pp. 155–177). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Skarlicki, D. P., & Latham, G. P. (2005). How can training be used to foster organizational justice? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), The handbook of organizational justice (pp. 3–56). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Snyder, M. (1974). The self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 526 –537. Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhardt (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290 –312). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. Stets, J. E. (2003). Emotions and sentiments. In J. DeLamater (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 309 –335). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. Sullins, E. S. (1989). Perceptual salience as a function of nonverbal expressiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 584 – 595. Tedeschi, J. T., & Felson, R. B. (1994). Violence, aggression, & coercive actions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Tourangeau, R., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1979). The role of facial response in the experience of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1519 –1531. Towler, A. J. (2003). Effects of charismatic influence training on attitudes, behavior, and performance. Personnel Psychology, 56, 363–381. Tsui, A. S., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1989). Beyond simple demographic effects: The importance of relational demography in superior-subordinate dyads. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 402– 423. Wageman, R. (2001). The meaning of interdependence. In M. E. Turner 1609 CHARISMA AND JUSTICE (Ed.), Groups at work: Theory and research (pp. 197–217). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Wasielewski, P. L. (1985). The emotional basis of charisma. Symbolic Interaction, 8, 207–222. Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guilford Press. Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS–X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule— expanded form. Unpublished manuscript, University of Iowa. Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1999). Issues in the dimensional structure of affect—Effects of descriptors, measurement error, and response formats: Comment on Russell and Carroll (1999). Psychological Bulletin, 125, 609 – 610. Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization (A. M. Henderson & T. Parsons, Trans.). New York: Free Press. (Original work published 1921) Williams, S., Pitre, R., & Zainuba, M. (2002). Justice and organizational citizenship behavior intentions: Fair rewards versus fair treatment. Journal of Social Psychology, 142, 33– 44. Yorges, S. L., Weiss, H. M., & Strickland, H. M. (1999). The effect of leader outcomes on influence, attributions, and perceptions of charisma. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 428 – 436. Received May 17, 2006 Revision received March 1, 2007 Accepted March 26, 2007 ! Members of Underrepresented Groups: Reviewers for Journal Manuscripts Wanted If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts for APA journals, the APA Publications and Communications Board would like to invite your participation. Manuscript reviewers are vital to the publications process. As a reviewer, you would gain valuable experience in publishing. The P&C Board is particularly interested in encouraging members of underrepresented groups to participate more in this process. If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts, please write to the address below. Please note the following important points: • To be selected as a reviewer, you must have published articles in peer-reviewed journals. The experience of publishing provides a reviewer with the basis for preparing a thorough, objective review. • To be selected, it is critical to be a regular reader of the five to six empirical journals that are most central to the area or journal for which you would like to review. Current knowledge of recently published research provides a reviewer with the knowledge base to evaluate a new submission within the context of existing research. • To select the appropriate reviewers for each manuscript, the editor needs detailed information. Please include with your letter your vita. In the letter, please identify which APA journal(s) you are interested in, and describe your area of expertise. Be as specific as possible. For example, “social psychology” is not sufficient—you would need to specify “social cognition” or “attitude change” as well. • Reviewing a manuscript takes time (1– 4 hours per manuscript reviewed). If you are selected to review a manuscript, be prepared to invest the necessary time to evaluate the manuscript thoroughly. Write to Journals Office, American Psychological Association, 750 First Street, NE, Washington, DC 20002-4242.