Das Human-Kapital: A Theory of the Demise of the Class Structure and

advertisement

Review of Economic Studies (2006) 73, 85–117

c 2006 The Review of Economic Studies Limited

0034-6527/05/00000000$02.00

Das Human-Kapital: A Theory of

the Demise of the Class Structure

ODED GALOR

Brown University

and

OMER MOAV

Hebrew University, Shalem Center and CEPR

First version received October 2004; final version accepted March 2005 (Eds.)

The history of society is the history of struggles between social classes.

Karl Marx

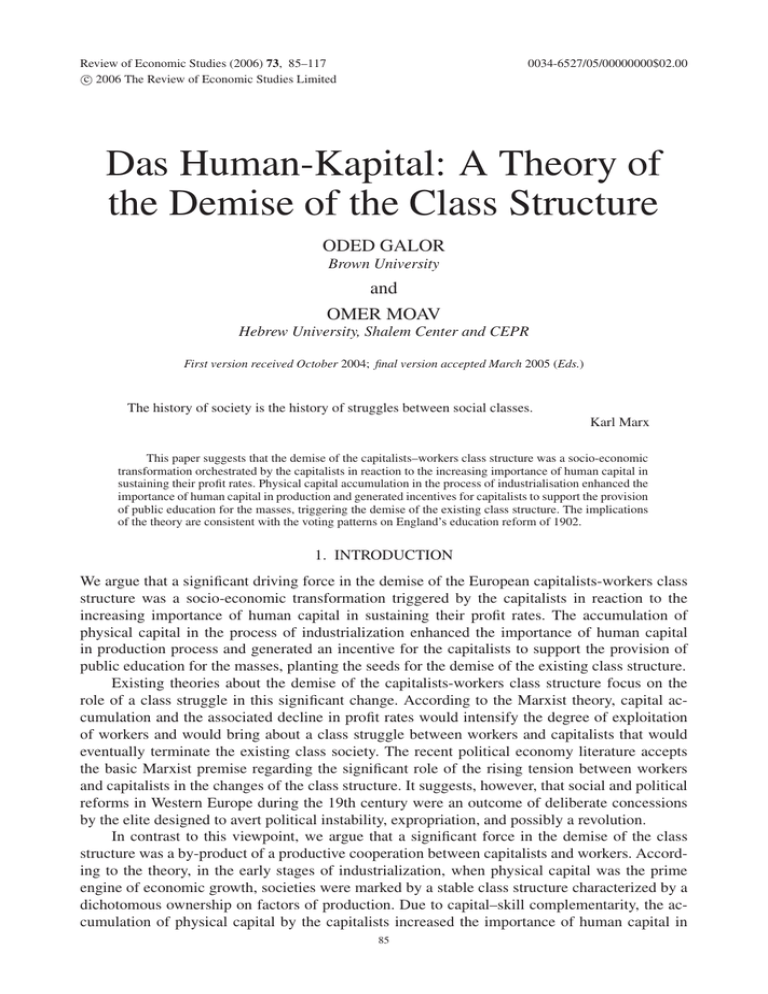

This paper suggests that the demise of the capitalists–workers class structure was a socio-economic

transformation orchestrated by the capitalists in reaction to the increasing importance of human capital in

sustaining their profit rates. Physical capital accumulation in the process of industrialisation enhanced the

importance of human capital in production and generated incentives for capitalists to support the provision

of public education for the masses, triggering the demise of the existing class structure. The implications

of the theory are consistent with the voting patterns on England’s education reform of 1902.

1. INTRODUCTION

We argue that a significant driving force in the demise of the European capitalists-workers class

structure was a socio-economic transformation triggered by the capitalists in reaction to the

increasing importance of human capital in sustaining their profit rates. The accumulation of

physical capital in the process of industrialization enhanced the importance of human capital

in production process and generated an incentive for the capitalists to support the provision of

public education for the masses, planting the seeds for the demise of the existing class structure.

Existing theories about the demise of the capitalists-workers class structure focus on the

role of a class struggle in this significant change. According to the Marxist theory, capital accumulation and the associated decline in profit rates would intensify the degree of exploitation

of workers and would bring about a class struggle between workers and capitalists that would

eventually terminate the existing class society. The recent political economy literature accepts

the basic Marxist premise regarding the significant role of the rising tension between workers

and capitalists in the changes of the class structure. It suggests, however, that social and political

reforms in Western Europe during the 19th century were an outcome of deliberate concessions

by the elite designed to avert political instability, expropriation, and possibly a revolution.

In contrast to this viewpoint, we argue that a significant force in the demise of the class

structure was a by-product of a productive cooperation between capitalists and workers. According to the theory, in the early stages of industrialization, when physical capital was the prime

engine of economic growth, societies were marked by a stable class structure characterized by a

dichotomous ownership on factors of production. Due to capital–skill complementarity, the accumulation of physical capital by the capitalists increased the importance of human capital in

85

86

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

sustaining the rate of return to physical capital and brought about a non-altruistic change in the

attitude of capitalists towards the provision of public education for the masses.1 The capitalists

found it beneficial to support universal publicly financed education, which enhanced the participation of the working class in the process of human and physical capital accumulation, and led to

a widening of the middle class and to the eventual demise of the capitalists–workers class structure.2 Thus, we argue that Karl Marx’s highly influential prediction about the inevitable class

struggle due to declining profit rates stemmed from an under-appreciation of the role that human

capital eventually played in the production process.

The theory is based on three central elements. First, the production process is characterized

by capital–skill complementarity.3 Capitalists therefore benefit from the aggregate accumulation

of human capital in society. Second, human capital is inherently embodied in individuals, and its

accumulation is characterized by decreasing marginal returns at the individual level. Hence, the

aggregate stock of human capital is larger if its accumulation is widely spread among individuals

in society. Capitalists therefore gain from a universal provision of education. Third, in the absence

of public education, investment in human capital is suboptimal due to borrowing constraints.

Therefore, public education enhances investment in human capital by the masses and may benefit

capitalists as well as workers.4

The theory suggests that the utilitarian support of capitalists for the provision of universal

public education was instrumental for the rapid formation of human capital and was therefore

a catalyst, and possibly even a necessary condition, for the demise of the class society. The

support for public education is unanimous among workers and capitalists who carry its prime

financial burden.5 That is, due to the coexistence of credit market imperfections and capital–skill

complementarity, the redistribution associated with public education is Pareto improving.6

The willingness of the capitalists to support universal public education rather than selective industrial education captures two of the underlying forces in the complementarity between

human capital and physical capital. First, it appears that in the second phase of the Industrial Revolution the increase in basic literacy that was associated with universal primary education raised

labour productivity. Second, investment in universal primary education generated a wider talent

pool for advanced industrial and managerial occupations, benefiting the production process at the

higher end.

1. Since firms have limited incentive to invest in the general human capital of their workers, in the presence of

credit market imperfections, the level of education would be suboptimal unless it would be financed publicly.

2. Indeed, the second phase of the Industrial Revolution was associated with a widening middle class of whitecollar workers, skilled artisans, and independent entrepreneurs (Cameron, 1989, p. 213). Moreover, the development

of the middle class was encouraged by industrialists who demanded not only a more educated labour force but also an

intermediate class of people who could serve in managerial and marketing positions (Anderson, 1975, p. 193).

3. See Goldin and Katz (1998) for evidence regarding capital–skill complementarity.

4. See Galor and Zeira (1993), Benabou (1996), Durlauf (1996), Fernandez and Rogerson (1996), and Galor and

Moav (2004) for the effect of credit market imperfections on investment in human capital and economic growth in an

unequal society. In particular, Galor and Moav (2004) offer a unified account for the effect of income inequality on the

process of development. They argue that the replacement of physical capital accumulation by human capital accumulation

as a prime engine of economic growth changed the qualitative impact of inequality on the process of development. In the

absence of an effective cooperation in the provision of public schooling, equality alleviates the adverse effect of credit

constraints and promotes human capital accumulation and economic growth.

5. The distribution of the cost of education between workers and capitalists may differ across countries due to

differences in their socio-political structure as well as their stage of development. Nevertheless, regardless of the distribution of political power in society, in light of the importance of nourishment and health for human capital formation and

labour supply, capitalists are unlikely to impose the prime financial burden on the working class as long as wages do not

significantly exceed the subsistence level of consumption.

6. This result is related to Benabou (2000), who demonstrates that when capital and insurance markets are imperfect, policies which redistribute wealth from richer to poorer individuals can have a positive net effect on aggregate output

and growth. Unlike the current study in which the support for growth-enhancing redistribution via public education is

unanimous, in Benabou (2000) redistributions are only supported by a wide consensus in a fairly homogeneous society

but face strong opposition in an unequal one. See Benabou (2002) as well.

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

87

Our thesis implies that a conflict of interest would emerge between owners of factors of

production that differ in their degree of complementarity with human capital. In particular, the

theory suggests that a conflict of interest about the timing of the implementation of growthenhancing educational policies would emerge primarily among the economic elites—industrialists

and landowners—rather than between the ruling elite and the masses.7

Historical evidence presented in Section 3 suggests that, consistent with the proposed theory,

the process of industrialization enhanced the importance of human capital in production and

induced the capitalists to lobby for the provision of universal public education. Furthermore, as

suggested by the theory, the acquisition of human capital by the working class in the second

phase of the Industrial Revolution and the associated increase in wages, in particular, relative to

the return to capital, brought about a gradual demise of the capitalist–workers class distinction.

The basic premise of this research, regarding the positive attitude of the capitalists towards

education reforms, is examined based on the voting patterns on the Balfour Act of 1902—the

proposed education reform in the U.K. that marked the consolidation of a national education system and the creation of a publicly supported secondary school system. Variations in the support

of MPs for the Balfour Act would be expected to reflect the variations in the skill intensity in the

counties they represent. Higher support for the Balfour Act would be expected from MPs who

represent industrial skill-intensive counties. The empirical analysis supports the main hypothesis.

It establishes that there exists a significant positive effect of skill intensiveness of the industrial

sector in a county on the propensity of the MPs to vote in favour of the education reform proposed

by the Balfour Act of 1902.

2. RELATED LITERATURE

The effect of social conflict on political and educational reforms was examined by Bowles and

Gintis (1975), Grossman (1994), Acemoglu and Robinson (2000), Bourguignon and Verdier

(2000), Grossman and Kim (2003), and Bertocchi and Spagat (2004), among others. They argue that reforms and redistribution from the elite to the masses diminish the tendency for sociopolitical instability and predation and may therefore stimulate investment and economic growth.

In particular, several studies examine the potential benefits for the elite from educational reforms.

Bourguignon and Verdier (2000) suggest that if political participation is determined by the education (socio-economic status) of citizens, the elite may not find it beneficial to subsidize universal

public education despite the existence of positive externalities from human capital. Grossman

and Kim (2003) argue that education decreases predation, and Bowles and Gintis (1975) suggest

that educational reforms are designed to sustain the existing social order, by displacing social

problems into the school system.

In contrast, we argue that a significant force in the demise of the class structure was a byproduct of a productive cooperation between capitalists and workers, rather than an outcome of

a divisive class struggle. Mutually beneficial reforms are also considered by Lizzeri and Persico

(2004) and Doepke and Zilibotti (2005). Lizzeri and Persico (2004) argue that provision of public

services may have served the interest of the elite as well as the masses, and therefore the extension

of franchise redirects resources from wasteful redistribution to public goods. Doepke and Zilibotti

(2005) argue that child labour regulation may benefit capitalists by inducing parents to educate

their children, increasing the average skill of the workforce. Although they place emphasis on

the political preference of the working class, since historically unions rather than factory owners

7. Galor, Moav and Vollrath (2003) examine the effect of a conflict of interest between capitalists and landowners

on education reforms. They establish theoretically and empirically the existence of a negative effect of land inequality on

public expenditure on education. Their findings support the thesis of this paper, demonstrating that even in the presence

of a class of landowners, cooperation between workers and capitalists, in the context of education reforms, may emerge.

88

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

were the main active campaigners for child labour regulation, the success of the unions’ action

may have been possible only because of diminished opposition from industrialists.

3. HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

Historical evidence suggests that, consistent with the proposed theory, a significant driving force

in the demise of the capitalists–workers class structure was the eagerness of the capitalists to invest

in the education of workers in reaction to the increasing importance of human capital in sustaining

their profit rates. In particular, Section 3.1 presents evidence that the process of industrialization

enhanced the importance of human capital in production and induced the capitalists to lobby

for the provision of universal public education. Section 3.2 provides evidence demonstrating

that the accumulation of human capital by the working class in the second phase of the Industrial

Revolution was associated with an increase in wages, in particular relative to the return to capital,

in line with a fading capitalists–workers class distinction. Finally, Section 3.3 presents evidence

that dispels an alternative hypothesis that political reforms during the 19th century shifted the

balance of power towards the working class and enabled workers to implement education reforms

against the will of the capitalists.

3.1. Industrial development and education reforms

Evidence suggests that the experience of the Western world throughout the various phases of the

Industrial Revolution is consistent with the hypothesis of this research about the link between

industrial development and educational reforms. The process of industrialization was characterized by a gradual increase in the relative importance of human capital for the production process

(Abramovitz, 1993). In the first phase of the Industrial Revolution, human capital had a limited

role in the production process. Education was motivated by a variety of reasons, such as religion,

social control, moral conformity, socio-political stability, social and national cohesion, military

efficiency, and the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment. The extensiveness of public education

was therefore not necessarily correlated with industrial development, and it differed across countries due to political, cultural, social, historical, and institutional factors.8 In the second phase

of the Industrial Revolution, education reforms were designed primarily to satisfy the increasing

skill requirements in the process of industrialization, reflecting the interest of capitalists in human capital formation and thus in the provision of public education.9 The evidence suggests that

in Western Europe, the economic interests of capitalists were indeed a significant driving force

behind the implementation of educational reforms.10

3.1.1. England. In the first phase of the Industrial Revolution (1760–1830), consistent with

the proposed hypothesis, capital accumulation increased significantly without a corresponding

increase in the supply of skilled labour.11 In contrast, literacy rates evolved rather slowly, and

the state devoted virtually no resources to raising the level of literacy of the masses.12 During

8. For instance, Sandberg (1979) argues that the level of human capital in Sweden prior to 1850 was larger than

the level that would have been justified by its stage of development.

9. The form of human capital that was complementary to physical capital was rather broad, including literacy,

quantitative abilities, and general knowledge, as well as work habits such as punctuality, discipline, manners, and diligence (Graff, 1987).

10. One could argue that the rise in income during the second phase of the Industrial Revolution brought about an

increase in education since people view education as a normal consumption good. The evidence that we provide in this

section clarifies that the mechanism that we underlined is a significant force behind the accumulation of human capital

during this period.

11. For instance, the investment ratio increased from 6% in 1760 to 11·7% in the year 1831 (Crafts, 1985, p. 73).

12. Cipolla (1969), Schofield (1973), and Cressy (1980) show that literacy rates have increased during the first

phase of the Industrial Revolution but at a slower rate than in the second phase.

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

89

the first stages of the Industrial Revolution, literacy was largely a cultural skill or a hierarchical symbol and had limited demand in the production process (Mitch, 1992; Mokyr, 1993,

2001). For instance, in 1841 only 4·9% of male workers and only 2·2% of female workers were

in occupations in which literacy was strictly required (Mitch, 1992, pp. 14–15). During this

period, an illiterate labour force could operate the existing technology, and economic growth was

not impeded by educational retardation.13 Workers developed skills primarily through on-the-job

training, and child labour was highly valuable (Kirby, 2003).

The development of a national public system of education in England lagged behind that

of the Continental countries by nearly half a century (Sanderson, 1995, pp. 2–10).14 Britain’s

early industrialization occurred without a direct state intervention in the development of the

minimal skills that were required in production (Green, 1990, pp. 293–294). Furthermore, as

argued by Landes (1969, p. 340) “although certain workers—supervisory and office personnel

in particular—must be able to read and do the elementary arithmetical operations in order to perform their duties, large share of the work of industry can be performed by illiterates as indeed it

was especially in the early days of the Industrial Revolution”.

England initiated a sequence of reforms in its education system since the 1830’s and literacy

rates gradually increased. The process was initially motivated by a variety of reasons such as

religion, social control, moral conformity, socio-political stability, and military efficiency, as

was the case in other European countries (e.g. Germany, France, Holland, Switzerland) that had

supported public education much earlier.15 However, in light of the modest demand for skills and

literacy by the capitalists, the level of governmental support was rather small.16

In the second phase of the Industrial Revolution, consistent with the proposed hypothesis,

the demand for skilled labour in the growing industrial sector markedly increased (Cipolla, 1969;

Kirby, 2003) and the proportion of children aged 5–14 in primary schools increased from 11% in

1855 to 25% in 1870 (Flora, Kraus and Pfenning, 1983).17 In light of the industrial competition

from other countries, capitalists started to recognize the importance of technical education for

the provision of skilled workers. As noted by Sanderson (1995, pp. 10–13), “reading . . . enabled

the efficient functioning of an urban industrial society laced with letter writing, drawing up wills,

apprenticeship indentures, passing bills of exchange, and notice and advertisement reading”.

Manufacturers argued that: “universal education is required in order to select, from the mass of

the workers, those who respond well to schooling and would make a good foreman on the shop

floor” (Simon, 1987, p. 104). Furthermore, in 1824, Alexander Galloway, the master-engineer,

reported: “I have found from the mode of managing my business, by drawings and written descriptions, a man is not of much use to me unless he can read and write. If a man applies for

work, and says he cannot read and write, he is asked no more questions” (Thompson, 1968).

13. Some have argued that the low skill requirements even declined over this period. For instance, Sanderson

(1995, p. 89) suggests that “One thus finds the interesting situation of an emerging economy creating a whole range of

new occupations which require even less literacy and education than the old ones”.

14. For instance, in his parliamentary speech in defence of his 1837 education bill, the Whig politician, Henry

Brougham, reflected upon this gap: “It cannot be doubted that some legislative effort must at length be made to remove

from this country the opprobrium of having done less for education of the people than any of the more civilised nations

on earth” (Green, 1990, pp. 10–11).

15. Wiener (1981), as well as others, argued in contrast that the educational system in Britain was initially designed

to accentuate and perpetuate class differences, however, with “little attention or status to industrial pursuits” (p. 24).

This pre-existing motivation for education had, therefore, a limited effect on the relative earnings of the elite and is thus

tangential to the hypothesis derived in this paper. Thus, although the aspects of education that were designed to accentuate

class differences may have affected the social characteristics of the elite and the masses, they have not counterbalanced

the trend towards the gradual participation of the decendants of the working class in the accumulation of physical and

human capital.

16. Even in 1869, the government funded only one-third of school expenditure (Green, 1990, pp. 6–7).

17. Job advertisements, for instance, suggest that literacy became an increasingly desired characteristic for employment as of the 1850’s (Mitch, 1993, p. 292).

90

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

As it became apparent that skills were necessary for the creation of an industrial society, capitalists had an increasing interest in the level of education of the masses.18 Initially, the capitalists

established the factory schools in order to educate the children they employed. The Factory Acts

of 1802 and 1833 made it mandatory for some manufacturers to set up such schools. These laws

were poorly enforced, and the factory schools were not widespread, nor were they well received

(Cipolla, 1969, pp. 66–69; Cameron, 1989, pp. 216–217; Smelser, 1991). The pure laissez-faire

policy failed in developing a proper educational system, and capitalists demanded government

intervention in the provision of education. As James Kitson, a Leeds iron-master and advocate

of technical education explained to the Select Committee on Scientific Instruction (1867–1868):

“. . . the question is so extensive that individual manufacturers are not able to grapple with it, and

if they went to immense trouble to establish schools they would be doing it in order that others

may reap the benefit” (Green, 1990, p. 295).

An additional turning point in the attitude of capitalists towards public education was the

Paris Exhibition of 1867, where the limitations of English scientific and technical education became clearly evident. Unlike the 1851 exhibition in which England won most of the prizes, the

English performance in Paris was rather poor; of the 90 classes of manufacturers, Britain dominated only in 10. Lyon Playfair, who was one of the jurors, reported that “a singular accordance

of opinion prevailed that our country has shown little inventiveness and made little progress in the

peaceful arts of industry since 1862”. This lack of progress was attributed to the fact that “France,

Prussia, Austria, Belgium and Switzerland possess good systems of industrial education and that

England possesses none” (Green, 1990, p. 296).

The government established various parliamentary investigations into the relationship between science, industry, and education, that according to the proposed theory, were designed to

address the capitalists’ outcry about the necessity of universal public education. A sequence of

reports by these committees in the years 1868–1882 underlined the inadequate training for supervisors, managers, and proprietors, as well as workers (Green, 1990, pp. 297–298). In particular,

W. E. Forster, the Vice President of the committee of the Council of Education told the House of

Commons: “Upon the speedy provision of elementary education depends our industrial prosperity . . . if we leave our work-folk any longer unskilled . . . they will become overmatched in the

competition of the world” (Hurt, 1971, pp. 223–224). They proposed to organize a state inspection of elementary and secondary schools and to provide efficient education geared towards the

specific needs of its consumers. In particular, the Royal Commission on Technical Education of

1882 confirmed that England was being overtaken by the industrial superiority of Prussia, France,

and U.S. and recommended the introduction of technical and scientific education into secondary

schools.

As argued in the proposed theory, it appears that the government gradually yielded to the

pressure by capitalists and increased its contributions to elementary as well as higher education. In the 1870 Education Act (prior to the significant extension of the franchise of 1884 that

made the working class the majority in most industrial counties), the government assumed responsibility for ensuring universal elementary education, although it did not provide either free

or compulsory education at the elementary level (Green, 1990, p. 299). School enrolment of

10 year olds increased from 40% in 1870 to 100% in 1900, the literacy rate among men increased

from 65% in the first phase of the Industrial Revolution, to nearly 100% at the end of the 19th

century (Clark, 2002), and the proportion of children aged 5–14 in primary schools increased significantly in the second half of the 19th century, from 11% in 1855 to 74% in 1900 (Flora et al.,

1983). Finally, the 1902 Balfour Act marked the consolidation of a national education system

18. As hypothesized in this paper, there was a growing consensus among workers and capitalists about the virtues of

education reforms. The labour union movement was increasingly calling for a national system of non-sectarian education

(Green, 1990, p. 302).

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

91

and created state secondary schools (Ringer, 1979). Furthermore, science and its application in

technology gained prominence (Mokyr, 1990, 2002). New universities were established with a

strong emphasis on professional training in the medical, legal, engineering, and economic studies

(Sanderson, 1995, p. 47).

3.1.2. Continental Europe. The early development of public education occurred in the

western countries of Continental Europe (e.g. Prussia, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands) well

before the Industrial Revolution. The process was motivated by a variety of reasons, such as religion, social control, moral conformity, socio-political stability, social and national cohesion, and

military efficiency (Scott, 1977; Graff, 1987). As was the case in England, massive educational

reforms occurred in the second half of the 19th century due to the rising demand for skills in the

process of industrialization (Cipolla, 1969). Technical and scientific education had been vigorously promoted as an essential element of competitiveness and economic growth (Green, 1990,

pp. 293–294).

In France, indeed, the initial development of the education system occurred well before

the Industrial Revolution, but the process was intensified and transformed to satisfy industrial

needs in the second phase of the Industrial Revolution. The early development of elementary and

secondary education in the 17th and 18th centuries was dominated by the church and religious

orders. Some state intervention in technical and vocational training was designed to reinforce development in commerce, manufacturing, and military efficiency. After the French Revolution, the

state established universal primary schools. Nevertheless, enrolment rates remained rather low.

The state concentrated on the development of secondary and higher education with the objective

of producing an effective elite to operate the military and governmental apparatus. Secondary education remained highly selective, offering general and technical instruction largely to the middle

class (Green, 1990, pp. 135–137 and 141–142). Legislative proposals during the National Convention quoted by Cubberle (1920, pp. 514–517) are revealing about the underlying motives for

education in this period: “. . . Children of all classes were to receive that first education, physical, moral and intellectual, the best adapted to develop in them republican manners, patriotism,

and the love of labour. . . They are to be taken into the fields and workshops where they may see

agricultural and mechanical operations going on. . . ”.

The process of industrialization in France and the associated increase in the demand for

skilled labour, as well as the breakdown of the traditional apprenticeship system, significantly affected the attitude towards education. State grants for primary schools were gradually increased

in the 1830’s and legislation made an attempt to provide primary education in all regions, extend

the higher education, and provide teacher training and school inspections. The number of communities without schools fell by 50% from 1837 to 1850, and as the influence of industrialists

on the structure of education intensified, education became more stratified according to occupational patterns (Anderson, 1975, pp. 15, 31). The eagerness of capitalists for rapid education reforms was reflected by the organization of industrial societies that financed schools specializing in

chemistry, design, mechanical weaving, spinning, and commerce (Anderson, 1975, pp. 86, 204).

As was the case in England, industrial competition led industrialists to lobby for the provision of public education. The Great Exhibition of 1851 and the London Exhibition of 1862

created the impression that the technological gap between France and other European nations

was narrowing and that French manufacturers ought to invest in the education of their labour

force to maintain their technological superiority. Subsequently, the reports on industrial education by commissions established in the years 1862–1865 reflected the plea of industrialists

for the provision of industrial education on a large scale and for the implementation of scientific knowledge in the industry. “The goal of modern education . . . can no longer be to form

men of letters, idle admirers of the past, but men of science, builders of the present, initiators

92

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

of the future”.19 (Anderson, 1975, p. 194). Education reforms in France were extensive in the

second phase of the Industrial Revolution, and by 1881 a universal, free, compulsory, and secular primary school system had been established and technical and scientific education further emphasized. Illiteracy rates among conscripts tested at the age of 20 declined gradually

from 38% in 1851–1855 to 17% in 1876–1880 (Anderson, 1975, p. 158), and the proportion

of children aged 5–14 in primary schools increased from 51% in 1850 to 86% in 1901 (Flora

et al., 1983).

In Prussia, as well, the initial steps towards compulsory education took place at the beginning of the 18th century well before the Industrial Revolution. Education was viewed at this stage

primarily as a method to unify the state (Schleunes, 1989; Tipton, 2003). In the second part of

the 18th century, education was made compulsory for all children aged 5–13. Nevertheless, these

regulations were not strictly enforced due to the lack of funding associated with the difficulty

of taxing landlords for this purpose and due to the loss of income from child labour.20 At the

beginning of the 19th century, motivated by the need for national cohesion, military efficiency,

and trained bureaucrats, the education system was further reformed, making education a secular

activity and compulsory for a three-year period, and reconstituting the Gymnasium as a state

institution providing nine years of education for the elite (Cubberley, 1920).

The process of industrialization in Prussia and the associated increase in the demand for

skilled labour led to significant pressure for educational reforms and thereby to the implementation of universal elementary schooling (Green, 1990). Taxes were imposed to finance the school

system, and teachers’ training and certification were established. Secondary schools started to

serve industrial needs as well. The Realschulen, which emphasized the teaching of mathematics and science was gradually adopted, and vocational and trade schools were founded. Total

enrolment in secondary school increased sixfold from 1870 to 1911 (Flora et al., 1983). “School

courses . . . had the function of converting the occupational requirements of public administration, commerce and industry into educational qualifications. . .” (Muller, 1987, pp. 23–24). Furthermore, the Industrial Revolution significantly affected the nature of education in German universities. German industrialists, who perceived advanced technology as the competitive edge that

could boost German industry, lobbied for reforms in the operation of universities and offered to

pay to reshape their activities so as to favour their interest in technological training and industrial

applications of basic research (McClelland, 1980, pp. 300–301).

Similarly, the structure of education in the Netherlands and Belgium reflected the interest

of capitalists in the skill formation of the masses. In the Netherlands, as early as the 1830’s, industrial schools were established and funded by private organizations, representing industrialists

and entrepreneurs. Ultimately, in the latter part of the 19th century, the state, urged by industrialists and entrepreneurs, started to support these schools (Wolthuis, 1999, pp. 92–93, 119,

139–140, 168, and 171–172). In Belgium, primary education was backward in comparison with

other European countries, and a compulsory education system was established only at the beginning of the 20th century, when the illiteracy rate was 19%. Nevertheless, industrial development

prompted the establishment of the industrial school as of 1818, financed by local industrialists.

These schools expanded rapidly in the middle of the 19th century (Mallinson, 1963).

3.1.3. United States. The process of industrialization in U.S. also increased the importance of human capital in the production process. Evidence provided by Abramovitz and David

19. L’Enseignement professionnel, ii (1864), p. 332, quoted in Anderson (1975).

20. Indicative of the realization by the elite that education was more significant for the urban production process is

the statement by Frederick II in 1779 about education: “... if they learn too much they will run off to the cities to become

secretaries or some such things” (Schleunes, 1989).

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

93

(2000) and Goldin and Katz (2001) suggests that over the period 1890–1999, the contribution of

human capital accumulation to the growth process of U.S. nearly doubled.21 As argued by Goldin

(1999), the rise of the industrial, business, and commerce sectors in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries increased the demand for managers, clerical workers, and educated sales personnel

who were trained in accounting, typing, shorthand, algebra, and commerce. Furthermore, in the

late 1910’s, technologically advanced industries demanded blue-collar craft workers who were

trained in geometry, algebra, chemistry, mechanical drawing, etc. The structure of education was

transformed in response to industrial development and the increasing importance of human capital in the production process, and high schools adapted to the needs of the modern workplace of

the early 20th century. Total enrolment in public secondary schools increased 70-fold from 1870

to 1950 (Kurian, 1994).

Nevertheless, due to differences in the structure of education finance in U.S. in comparison

to European countries, capitalists in U.S. had only limited incentives to lobby for the provision

of education and support it financially. Unlike the central role that government funding played in

the provision of public education in European countries, the evolution of the education system in

U.S. was based on local initiatives and funding. The local nature of the education initiatives

in U.S. induced community members, in urban as well as rural areas, to play a significant role

in advancing their schooling system. Capitalists, however, faced limited incentives to support the

provision of education within a county in an environment where labour was mobile across counties, and the benefits from educational expenditure in one county could be reaped by employers

in other counties.

3.2. Schooling, factor prices, and inequality

The main hypothesis of this research suggests that in the first phase of the Industrial Revolution, prior to the implementation of significant education reforms, physical capital accumulation

was the prime engine of economic growth, and the concentration of capital among the capitalist class widened wealth inequality. Once education reforms were implemented, however, the

significant increase in the return to labour relative to capital, as well as the significant increase

in the real return to labour and the associated accumulation of assets by the workers, brought

about a decline in inequality and eventually the demise of the European 19th-century class

structure.22

The theory predicts that in the first phase of the Industrial Revolution, prior to the implementation of education reforms, capital accumulation brought about a gradual increase in wages

along with an increase in the wage–rental ratio. Education reforms in the second phase of the

Industrial Revolution are expected to generate a sharp increase in real wages along with a sharp

increase in the wage–rental ratio. Finally, wealth inequality is predicted to widen in the first

phase of the Industrial Revolution and to reverse its course in the second phase, once significant

education reforms have been implemented.

Indeed, evidence from U.K. supports this hypothesis. As depicted in Figure 1(c) and (d),

based on the data-set of Clark (2002, 2005), real wages as well as the wage–rental ratio increase

21. It should be noted that literacy rates in U.S. were rather high prior to this increase in the demand for skilled

labour. Literacy rates among the white population were already 89% in 1870, 92% in 1890, and 95% in 1910 (Engerman

and Sokoloff, 2002). Education in earlier periods was motivated by social control, moral conformity, and social and

national cohesion, as well as required skills for trade and commerce.

22. The rise in inequality in mature stages of development due to technological acceleration (e.g. Galor and Tsiddon,

1997; Caselli, 1999; Galor and Moav, 2000) does not reflect a reversal in the demise of the class structure. It is not related

to class association as reflected partly by increased intergenerational mobility (e.g. Galor and Tsiddon, 1997; Maoz and

Moav, 1999; Hassler and Rodriguez-Mora, 2000).

94

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

Source: Flora et al. (1983), real wage (Clark, 2005), rental rates (Clark, 2002), real wage (Clark,

2005), and return to capital (Clark, 2002).

F IGURE 1

Schooling, factor prices, and inequality, England 1770–1920. The evolution of (a) the fraction of children aged 5–14 in

public primary schools: England, 1855–1920, (b) earnings inequality: England, 1820–1913, (c) wages and rental rates:

England, 1770–1920, and (d) the wage–rental ratio: England, 1770–1920

dramatically from 1870 well into the 20th century.23 These changes in factor prices reflect the

increase in enrolment rates, as depicted in Figure 1(a) (in particular the process of education

reforms from 1830 to 1870 and its consolidation in the Education Act of 1870) and its delayed

effect on the skill level per worker.24 Thus, it appears that the demise of the class structure is

indeed associated with the significant changes that occurred around 1870 in the relative returns

to the main factors of production possessed by capitalists and workers.25 As documented in the

controversial study by Williamson (1985) about the evolution of inequality in the time period

1823–1915, wealth inequality in U.K. reached a peak around 1870 and declined thereafter (Figure

1(b)), in close association with the patterns of enrolment rates and factor prices.26

23. Clark (2005) constructs three series for wages in England over this period: Farm wage, Helper wage, and

Craftsmen wage. Figures 1(c) and (d) are based on Helper wage. (Craftsmen wage generate similar time path.) Farm

wage appears less relevant given the focus of the paper. Moreover, it should be noted that the return to capital increased

moderately over this period, despite the increase in the supply of capital, reflecting technological progress, population

growth, and accumulation of human capital.

24. It should be noted that although the demand for skill labour increased in the process, the skill premium is rather

stable over this period (Clark, 2005). The lack of clear evidence about the increase in the return to human capital over

this period is not an indication for the absence of a significant increase in the demand for human capital. However, the

significant increase in schooling that took place in the 19th century, and in particular the introduction of public education

that lowered the cost of education, generated a significant increase in the supply of educated workers and operated towards

a reduction in the return to human capital.

25. Throughout the period 1873–1913 in which real wages increase significantly, the growth rate of output per

capita is explained entirely by the contributions of physical and human capital accumulation. (Matthews, Feinstein and

Odling-Smee, 1982). An increase in labour-augmenting technological change is therefore not a viable explanation for

relative and absolute increases in real wages and the decline in inequality in U.K. over this period.

26. Feinstein (1988), criticizes Williamson’s methodology of data construction, but does not provide an alternative

that refutes the hump-shaped evolution of inequality over this period.

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

95

Source: Flora et al. (1983), Morrisson and Snyder (2000), Levy-Leboyer and Bourguignon

(1990), and Levy-Leboyer and Bourguignon (1990).

F IGURE 2

Schooling, factor prices, and inequality, France 1770–1930. The evolution of (a) the fraction of children aged 5–14

in primary schools: France, 1830–1910, (b) wealth inequality: France, 1788–1929, (c) the real wage and rental rate:

France, 1820–1913, and (d) the wage–rental ratio: France, 1820–1913

Similar patterns of the effect of education on factor prices and therefore on inequality are

observed in France as well. As argued by Morrisson and Snyder (2000), wealth inequality in

France increased during the first half of the 19th century, and as depicted in Figure 2(b), started to

decline in the last decades of the 19th century in close association with the patterns of enrolment

rates and factor prices, depicted in Figure 2(a), (c), and (d). The decline in inequality in France

appears to be associated with the significant changes in the relative returns to the main factors

of production possessed by capitalists and workers in the second part of the 19th century. As

depicted in Figure 2(c) and (d), based on the data presented in Levy-Leboyer and Bourguignon

(1990), real wages as well as the wage–rental ratio increase significantly as of 1860, reflecting

the effect of the increase in enrolment rates on the skill level per worker.

The German experience is consistent with this pattern as well. Inequality in Germany started

to decline towards the end of the 19th century (Morrisson and Snyder, 2000) in association with a

significant increase in the real wages and in the wage–rental ratio from the 1880’s (Spree, 1977;

Berghahn, 1994), which is in turn related to the provision of industrial education in the second

half of the 19th century.

The link between the expansion of education and the reduction in inequality is present in

U.S. as well. Wealth inequality in U.S., which increased gradually from colonial times until the

second half of the 19th century, reversed its course at the turn of the century and maintained its declining pattern during the first half of the 20th century (Lindert and Williamson, 1976). As argued

by Goldin (2001), the emergence of the “new economy” in the early 20th century increased the

demand for educated workers. The creation of publicly funded mass modern secondary schools

from 1910 to 1940 provided general and practical education, contributed to workers’ productivity, and opened the gates for college education. This expansion facilitated social and geographic

mobility and generated a large decrease in inequality in economic outcomes.

96

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

Source: Flora et al. (1983).

F IGURE 3

The evolution of voting rights and school enrolment: (a) England, 1830–1925 and (b) France, 1820–1925

3.3. The timing of educational and political reforms

This research suggests that education reforms were initiated by the capitalists in reaction to the

increasing importance of human capital in sustaining their profit rates. An alternative hypothesis

may be that political reforms during the 19th century shifted the balance of power towards the

working class and enabled workers to implement education reforms against the will of the elite.27

The evidence, however, does not support this alternative hypothesis.

Education reforms took place in autocratic states that did not relinquish political power

throughout the 19th century, and major reforms occurred in societies in the midst of the process of democratization well before the stage at which the working class constituted the majority

among the voters. In particular, the most significant education reforms in U.K. were completed

before the voting majority shifted to the working class. The patterns of education and political reforms in U.K. during the 19th century are depicted in Figure 3(a). The Reform Act of

1832 nearly doubled the total electorate, but nevertheless only 13% of the voting age population was enfranchised. The artisans, the working classes, and some sections of the lower middle

classes remained outside of the political system. The franchise was extended further in the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884 and the total electorate nearly doubled in each of these episodes.

However, working-class voters did not become the majority in all urban counties until 1884

(Craig, 1989).

The onset of England’s education reforms, and in particular, the fundamental Education Act

of 1870 and its major extension in 1880, occurred prior to the political reforms of 1884 that made

the working class the majority in most counties. As depicted in Figure 3(a), a trend of significant

increase in primary education was established well before the extension of the franchise in the

context of the 1867 and 1884 Reform Acts. In particular, the proportion of children aged 5–14

in primary schools increased fivefold (and surpassed 50%) over the three decades prior to the

qualitative extension of the franchise in 1884 in which the working class was granted a majority

in all urban counties. Furthermore, the political reforms do not appear to have any effect on the

pattern of education reform. In fact, the average growth rate of education attendance from decade

27. See, for instance, Acemoglu and Robinson (2000), where the extension of the franchise during the 19th century

is viewed as a commitment devise to ensure future income redistribution from the elite to the masses.

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

97

to decade over the period 1855–1920 reaches a peak at around the Reform Act of 1884 and starts

declining thereafter.28

A similar pattern was seen in other European countries. In France, the expanding pattern of

education preceded the major political reform that gave the voting majority to the working class.

The patterns of education and political reforms in France during the 19th century are depicted

in Figure 3(b). Prior to 1848, restrictions limited the electorate to less than 2·5% of the voting

age population. The 1848 revolution led to the introduction of nearly universal voting rights

for males. Nevertheless, the proportion of children aged 5–14 in primary schools doubled (and

exceeded 50%) over the two decades prior to the qualitative extension of the franchise in 1848 in

which the working class was granted a majority among voters. Furthermore, the political reforms

of 1848 do not appear to have any effect on the pattern of education expansion. In the Netherlands,

political reforms did not affect the trend of education expansion and the proportion of children

aged 5–14 in primary schools exceeded 60% well before the major political reforms of 1887 and

1897. Similarly, the trends of political and education reforms in Sweden, Italy, Norway, Prussia,

and Russia do not lend credence to the alternative hypothesis.

4. THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF THE MODEL

Consider a closed overlapping generations economy in a process of development. In every period

the economy produces a single homogeneous good that can be used for consumption and investment. The good is produced using physical capital and human capital. Output per capita grows

over time due to the accumulation of these factors of production.29 The stock of physical capital

in every period is the output produced in the preceding period net of consumption and human

capital investment, whereas the stock of human capital in every period is determined by the aggregate level of public education in the preceding period.30

4.1. Production of final output

Production occurs within a period according to a neoclassical, constant-returns-to-scale, production technology. The output produced at time t, Yt , is

Yt = F(K t , Ht ) ≡ Ht f (kt ) = AHt ktα ; kt ≡ K t /Ht ; α ∈ (0, 1),

(1)

where K t and Ht are the quantities of physical capital and human capital (measured in efficiency

units) employed in production at time t, and A is the level of technology.31 The production function, f (kt ), is therefore strictly increasing, strictly concave satisfying the neoclassical boundary

28. It is interesting to note, however, that the abolishment of education fees in nearly all elementary schools occurs

only in 1891, after the Reform Act of 1884, suggesting that the political power of the working class may have affected

the distribution of education cost across the population, but consistent with the proposed thesis, the decision to educate

the masses was taken independently of the political power of the working class.

29. Earlier growth models that focus on the role of physical and human capital in the process of development

include, for instance, Lucas (1988), Caballe and Santos (1993), and Mulligan and Sala-i-Martin (1993). These models

abstract from the analysis of income heterogeneity and credit market imperfections, and therefore, do not study the

incentives of the rich to subsidize the education of the poor.

30. The model abstracts from international factor movements. Land abundance in America has generated incentives

for outflow of labour from Europe to America, intensifying the problem of labour scarcity and preventing the use of labour

inflow (rather than investment in human capital) as a remedy for labour scarcity. In contrast, as argued by Taylor (1999)

and O’Rourke, Taylor and Williamson (1996), international capital outflow from Britain was significant during the 19th

century and hence could alleviate some of the need to invest in human capital in order to sustain the profit rates.

31. The introduction of technological progress would accelerate the rise in wages and may eventually trigger the

demise of the class structure even in the absence of education reforms. Nevertheless, educational reforms would have

a significant role in expediting the process. Moreover, it should be noted, that consistent with empirical evidence TFP

growth over the relevant period for this study is negligible and output growth is based primarily on factor accumulation,

as underlined in the proposed theory.

98

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

conditions that assure the existence of an interior solution to the producers’ profit-maximization

problem.

Producers operate in a perfectly competitive environment. Given the wage rate per efficiency

unit of labour, wt , and the rate of return to capital, rt , producers in period t choose the level of

employment of capital, K t , and efficiency units of labour, Ht , so as to maximise profits. That

is, {K t , Ht } = arg max [Ht f (kt ) − wt Ht − rt K t ]. The producers’ inverse demand for factors of

production is therefore

rt = f (kt ) = α Aktα−1 ≡ r (kt );

wt = f (kt ) − f (kt )kt = (1 − α)Aktα ≡ w(kt ).

(2)

4.2. Individuals

In every period a generation which consists of a continuum of individuals of measure 1 is born.

Each individual has a single parent and a single child. Individuals, within as well as across generations, are identical in their preferences and innate abilities. They may differ, however, in their

family wealth and thus, due to borrowing constraints, in their capability to finance investment in

human capital in the absence of public education.

Individuals live for two periods. In the first period of their lives individuals devote their

entire time for the acquisition of human capital. The acquired level of human capital increases if

their time investment is supplemented with capital investment in education. In the second period

of their lives, individuals supply their efficiency units of labour and allocate the resulting wage

income, along with their interest income, between consumption and transfers to their children.

An individual i born in period t (a member i of generation t) receives a parental transfer, bti ,

in the first period of life. A fraction τt ≥ 0 of this capital transfer is collected by the government

in order to finance public education, whereas a fraction 1 − τt is saved for future consumption.

Individuals devote their first period for the acquisition of human capital. Education is provided

publicly free of charge.32 The acquired level of human capital increases with the real resources

invested in public education. The number of efficiency units of labour of each member of generation t in period t + 1, h t+1 , is a strictly increasing, strictly concave function of the government

real expenditure on education per member of generation t, et .33

h t+1 = h(et ),

(3)

where h(0) = 1, h (0) = γ < ∞, and limet →∞ h (et ) = 0. The assumption that the slope of the

production function of human capital is finite at the origin along with the assumption that each

individual has a minimal level of human capital, h(0) > 0, even in the absence of a real expenditure on education, assure that under some market conditions investment in human capital is not

optimal.34

32. As will become apparent, once the level of public education is chosen, individuals have no incentive to acquire

private education. In particular, in early stages of development, when the tax rate τt equals 0, individuals do not acquire

education.

33. A more realistic formulation would link the cost of education to (teachers’) wages, which may vary in the

process of development. For instance, h t+1 = h(et /wt ) implies that the cost of education is a function of the number of

efficiency units of teachers that are used in the education of each individual i. As can be derived from Section 3.4, under

both formulations the optimal expenditure on education, et , is an increasing function of the capital–labour ratio in the

economy, and the qualitative results are therefore identical.

34. These assumptions are necessary in order to assure that in the early stage of development the sole engine of

growth is physical capital accumulation and there is no incentive to invest in human capital. It permits, therefore, a sharp

presentation of the results regarding institutional transition. The typically assumed Inada condition (i.e. γ is infinite) is

designed to simplify the exposition by avoiding a corner solution, but it is not a realistic assumption.

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

99

In the second-period life, a member i of generation t supplies the acquired efficiency units of

labour, h t+1 , at the competitive market wage, wt+1 . In addition, the individual receives the gross

i , is therefore

return on savings, (1 − τt )bti Rt+1 . The individual’s second-period income, It+1

i

It+1

= wt+1 h(et ) + (1 − τt )bti Rt+1 ,

(4)

where due to complete capital depreciation Rt+1 ≡ rt+1 ≡ R(kt+1 ).

Preferences of a member i of generation t are defined over second-period consumption,

i , and the transfer to their offspring, bi .35 They are represented by a non-homothetic, logct+1

t+1

linear utility function that generates the property that the average propensity to bequest is an

increasing function of wealth:36

i

i

u it = (1 − β) log ct+1

+ β log(θ + bt+1

),

(5)

where β ∈ (0, 1) and θ > 0.37

Hence, a member i of generation t allocates second-period income between consumption,

i , and transfers to the offspring, bi . That is,

ct+1

t+1

i

i

i

ct+1

+ bt+1

≤ It+1

.

(6)

i , and a non-negative transfer

The individual chooses the level of second-period consumption, ct+1

i

to the offspring, bt+1 , so as to maximize the utility function subject to the second-period budget

constraint (6).38

Hence the optimal transfer of a member i of generation t is

i

bt+1

i

= b(It+1

)≡

i

− θ)

β(It+1

if

i

It+1

>θ

0

if

i

It+1

≤ θ,

(7)

where θ ≡ θ(1 − β)/β.

35. For simplicity, we abstract from first-period consumption. It may be viewed as part of the consumption of the

parent.

36. This utility function represents preferences under which the saving rate is an increasing function of wealth. This

classical feature (e.g. Keynes, 1920; Lewis, 1954; Kaldor, 1957) is consistent with empirical evidence. Dynan, Skinner

and Zeldes (2004) find a strong positive relationship between personal saving rates and lifetime income in U.S. They

argue that their findings are consistent with models in which precautionary saving and bequest motives drive variations

in saving rates across income groups. Furthermore, Tomes (1981) and Menchik and David (1983) find evidence that the

marginal propensity to bequeath increases with wealth. The choice of a non-homothetic utility function is necessary to

assure that workers do not invest in physical capital prior to the establishment of public schooling. A choice of a homothetic utility function would not affect the results regarding the effect of capital skill complementarity on institutional

transition, but it would imply that the demise of the class structure would have necessarily occurred even in the absence

of education reforms. Nevertheless, even under homothetic preferences, educational reforms would have a significant

role in expediting the process.

37. This form of altruistic bequest motive (i.e. the “joy of giving”) is the common form in the recent literature on

income distribution and growth. It is supported empirically by Altonji, Hayashi and Kotlikoff (1997). Utility from after

tax transfers would reduce intergenerational transfers but would not affect the qualitative results. In particular, under

utility from net transfers equation(7) below would be

i − θ/(1 − τ

i

β(It+1

t+1 )), if It+1 > θ/(1 − τt+1 )

i

i ,τ

bt+1

.

= b(It+1

)

≡

t+1

i

≤ θ/(1 − τt+1 )

0,

if It+1

i , is necessarily non-negative due to the assumption that the offspring

38. It should be noted that the transfer, bt+1

has no income in the first period of life.

100

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

4.3. Physical capital, human capital, and output

This section demonstrates that the stocks of physical and human capital and therefore the level of

output are determined by the aggregate level of intergenerational transfers, the level of taxation,

and governmental expenditure on public education in the preceding period.

Let Bt denote the aggregate level of intergenerational transfers in period t. A fraction τt of

this capital transfer is collected by the government in order to finance public education, whereas

a fraction 1 − τt is saved for future consumption.39 The capital stock in period t + 1, K t+1 , is

therefore

K t+1 = (1 − τt )Bt ,

(8)

whereas the government tax revenues are τt Bt .

Since population is normalized to 1, the education expenditure per young individual in

period t, et , is

(9)

et = τt Bt ,

and the stock of human capital in period t + 1, Ht+1 , is therefore

Ht+1 = h(et ) = h(τt Bt ).

(10)

Hence, the capital–labour ratio kt+1 ≡ K t+1 /Ht+1 is

kt+1 =

(1 − τt )Bt

≡ k(τt , Bt ),

h(τt Bt )

(11)

where k(0, Bt ) = Bt , ∂k(τt , Bt )/∂τt < 0, ∂k(τt , Bt )/∂ Bt > 0, 40 and the output per worker in

period t + 1 is

yt+1 = A[(1 − τt )Bt ]α h(τt Bt )1−α ≡ y(τt , Bt ).

(12)

4.4. Optimal taxation

This section derives the optimal tax rate and therefore the optimal expenditure on education from

the viewpoint of each individual in society. It demonstrates that as long as taxation is used in

order to finance public schooling, there is a consensus in society regarding the desirable tax rate.

If the government would be engaged in direct transfers from the rich to the poor in addition to

the provision of public schooling, then a conflict would emerge between the classes regarding the

desirable tax rate. This would perhaps add some realism, but would obscure unnecessarily the

focus on the role of cooperative forces in the demise of the class structure.

Given that the indirect utility function is a strictly increasing function of the individual’s

second-period wealth, the optimal tax rate, τti , from the viewpoint of member i of generation t,

(and hence the optimal expenditure on education, et = τti Bt from the viewpoint of this individual,

i .

given Bt ) would maximize the individual’s second period wealth, It+1

τti = arg max[wt+1 h(τti Bt ) + (1 − τti )bti Rt+1 ],

(13)

where wt+1 = w(kt+1 ) and Rt+1 = R(kt+1 ).

39. As will become apparent, this linear tax structure is the simplest structure that would generate the transition

from a class society. It assures that the chosen level of taxation is independent of the structure of the political system.

That is, independent of the distribution of political power or voting rights among members of society. Furthermore,

capitalists could have not effectively forced the poor to finance their own education due to the proximity of the income

of the poor to the subsistence level of consumption and the positive effect of income of the outcome of the education

process.

40. ∂k(τt , Bt )/∂ Bt > 0 if and only if h(et ) − h (et )et > 0, which is satisfied given the strict concavity of h(et ) and

the positivity of h(0).

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

101

As follows from (13), noting (2) and (11) the optimal tax rate from the viewpoint of a

member i of generation t, τti , is given by41

w(kt+1 )h (τti Bt ) = R(kt+1 )

for

τti > 0 and

w(kt+1 )γ ≤ R(kt+1 )

for

τti = 0,

(14)

where kt+1 = k(τt , Bt ). Hence, given Bt , τti is determined independently of bti , and is therefore

identical for all i.42 That is τti = τt∗ for all i. Furthermore, there exists a unique capital–labour

ratio k, below which τti = 0. That is, R(

k) = w(

k)γ .

Lemma 1.

(i) The optimal tax rate in period t, τt∗ , is identical from the viewpoint of all members of

generation t and is uniquely determined.

τt∗

= τ (Bt )

>0

f or

Bt > k

=0

f or

k

Bt ≤ k = α/(1 − α)γ .

(ii) The optimal expenditure on public education, et = τ (Bt )Bt ≡ e(Bt ) from the viewpoint of

k.

each member of generation t is strictly increasing in Bt , for Bt > Proof. Noting (2), (11), and (14), it follows from the properties of h(τt Bt ) that τt∗ is

k and (2),

uniquely determined by Bt and e (Bt ) > 0, where as follows from the definition of k = α/(1 − α)γ . Hence, since the optimal tax rate in period t is identical from the viewpoint of each member

of generation t, it follows that under any political structure, the chosen tax rate in period t is

τt = τt∗ = τ (Bt ).

(15)

Proposition 1. The tax rate in period t, τt , is

⎧

⎨> 0 f or kt+1 > k

τt

.

⎩= 0 f or k

k

t+1 ≤ Proof. Since h(0) = 1, it follows from (11), (14), and Lemma 1 that kt+1 = Bt for Bt ≤ k

k. Thus the proposition follows. and hence for kt+1 ≤ 41. Substituting (2) and (11) into (13),

τti = arg max(1 − τti )α h(τti Bt )1−α Bt α [1 − α + αbti /Bt ].

The conditions in (14) follow from the optimization problem above, using (2).

42. The unanimous agreement on the tax rate is a result of the linear tax rate and the unit elasticity of substitution

between human and physical capital in production. Given a Cobb–Douglas production function, the shares of labour and

capital are constant and wage and capital income are therefore maximized if output is maximized. If the elasticity of

substitution would be larger than unity, then the poor would prefer higher taxes, whereas if the elasticity of substitution

is smaller than unity, then the rich would prefer higher taxes.

102

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

Corollary 1. The chosen level of taxation in every period maximizes output per worker in

the following period. That is,

τt = arg max yt+1 ≡ arg max y(τt , Bt ).

Proof. Maximizing y(τt , Bt ) with respect to τt yields the optimality conditions given by

(14), that is, the optimality conditions for the desired level of taxation from the viewpoint of each

individual. Hence, as long as the rate of return to human capital is lower than the rate of return on

k), the chosen level of investment in public education is

physical capital (i.e. as long as kt+1 ≤ 0—the level of investment that maximizes output per worker. Once the rate of return to human

capital equals the rate of return on physical capital (i.e. once kt+1 > k), the chosen investment in

public education is positive, and it maximizes output per worker.

4.5. The dynamical system

This section derives the properties of the dynamical system that governs the evolution of the

economy in the transition from a class society to a classless society. It demonstrates that the

evolution of the economy is fully determined by the evolution of intergenerational transfer within

classes in society.

Suppose that in period 0 the economy consists of two groups of individuals in their first

period of their lives—capitalists and workers. They are identical in their preferences and differ

only in their initial wealth. The Capitalists, denoted by R (Rich), are a fraction λ of all individuals

in society, who equally own the entire initial stock of wealth. The Workers, denoted by P (Poor),

are a fraction 1 − λ of all individuals in society, who have no ownership over the initial physical

capital stock.43 Since individuals are initially homogenous within a group, the uniqueness of the

solution to their optimization problem assures that their offspring who acquire the same level of

education and are taxed equally are homogenous as well . Hence, in every period a fraction λ of

all adults are homogenous descendants of the Capitalists, denoted by members of group R, and a

fraction 1 − λ are homogenous descendants of Workers, denoted by members of group P.

The optimization of groups P and R of generation t − 1 in period t > 0, determines the

aggregate intergenerational transfers in period t, Bt .

Bt = λbtR + (1 − λ)btP ≡ B(btR , btP ),

(16)

where bti is the intergenerational transfer of each member of group i in period t; i = P, R.

Hence, the capital–labour ratio in period t + 1, kt+1 , is fully determined by the intergenerational transfers of the two groups. As follows from (11), (15), (16), and Proposition 1,

kt+1 =

[1 − τ (Bt )]Bt

≡ κ(btR , btP ),

h[τ (Bt )Bt ]

(17)

where as follows from (2) and (14), and the properties of (11), ∂κ/∂bti > 0, i = R, P. Furthermore, κ(0, 0) = 0 (since in the absence of transfers and hence savings the capital stock in the

subsequent period is 0).

Since members of group R equally own the entire initial stock of wealth in period 0 and

members of group P have no ownership over the initial stock of wealth, it follows that b0R > 0

p

and b0 = 0.

43. As will become apparent this class distinction will dissipate over time. In particular, descendants of the working

class will ultimately own some physical capital.

GALOR & MOAV

Lemma 2.

period 0.

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

103

If b0R < k/λ then k1 < k, and thus there is no investment in public education in

p

Proof. Since b0 = 0, (11), (16), and Lemma 1, given the properties of (3), imply that

k1 = B0 = λb0R . Hence, it follows that k1 < k and thus, as follows from Proposition 1, τ0 = 0.

Consistently with empirical evidence about the process of development, it is therefore

assumed that

b0R < k/λ,

(A1)

namely, there is no investment in public education in the early stage of development.

The evolution of transfers within each group i = R, P, as follows from (7), is given by

i

= max{β[w(kt+1 )h(τ (Bt )Bt ) + (1 − τ (Bt ))bti R(kt+1 ) − θ], 0},

bt+1

i = R, P.

(18)

Since kt+1 = κ(btR , btP ), and Bt = B(btR , btP ), the evolution of transfers of each of the two groups

is fully determined by the evolution of transfers of both types of dynasties. Namely,

i

bt+1

= max{β[w(κ(btR , btP ))h(τ (B(btR , btP ))B(btR , btP ))

+ (1 − τ (B(btR , btP )))bti R(κ(btR , btP )) − θ ], 0}

≡ ψ i (btR , btP ),

i = R, P.

(19)

(20)

Thus, the dynamical system is uniquely determined by the joint-evolution of the intergenerational transfers of Workers, P and Capitalists, R. Hence, the evolution of the economy is given

by the sequence {btP , btR }∞

t=0 that satisfies in every period

P

= ψ P (btR , btP );

bt+1

R

bt+1

= ψ R (btR , btP ),

(21)

p

where b0 = 0 and b0R > 0.

5. THE PROCESS OF DEVELOPMENT

This section analyses the endogenous demise of the Capitalists–Workers class structure as the

economy evolves from early to mature stages of development.

5.1. Regime I: Physical capital accumulation

This early stage of development is characterized by a stable class structure. Capitalists generate a

higher rate of return from a direct investment in physical capital, rather than from supporting the

education of Workers that would complement their capital in the production process. Capitalists

therefore have no incentive to financially support the education of the Workers.

Regime I is defined as the time interval 0 ≤ t < t, where t + 1 is the first period in which

the capital–labour ratio exceeds k (i.e. t is the first period in which investment in human capital

takes place). In this early stage of development the capital–labour ratio in period t + 1, kt+1 ,

which determines the investment in public education in period t, is lower than k. As follows

from Proposition 1 and Corollary 1, the tax rate is 0, there is no public education, and both

groups of individuals acquire only basic skills. That is, Ht+1 = h(0) = 1.

104

REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

Let ǩ be the level of the capital–labour ratio such that w(ǩ) = θ. As follows from (4), ǩ is

the critical level of the capital–labour ratio in time t + 1 below which in the absence of public

investment in education in period t individuals who do not receive transfers from their parents in

i

period t do not transfer income to their offspring in period t + 1. That is, It+1

≤ θ, and therefore

i

bt+1 = 0.

In order to assure that investment in human capital will begin in a period where the poor do

not invest in physical capital, it is assumed therefore that44

k ≤ ǩ.

(A2)

k = α/(1 − α)γ , Assumption A2 implies thereAs follows from (2), ǩ = [θ/(1 − α)A]1/α . Since fore that γ > (α α (1 − α)1−α A/θ)1/α .

Lemma 3. Under Assumptions A1 and A2, there are no intergenerational transfers among

workers (i.e. btP = 0) as long as public education is not established, that is,

btP = 0 for 1 ≤ t ≤ t.

Proof. As follows from Proposition 1, the definition of t, and Assumption A1 that

assures that t > 1, for 0 ≤ t < t, there is no investment in public education and hence h t+1 = 1.

P =

Hence, since Assumption A2 implies that kt ≤ ǩ and therefore w(kt ) ≤ θ, it follows that bt+1

P

P

P

max[β[w(kt+1 ) − θ ] , 0] = 0 if bt = 0. Since b0 = 0, it follows, therefore, that bt = 0 for 1 ≤

t ≤

t. The capital–labour ratio in period t + 1, as follows from (16), (17), Proposition 1, and

Lemma 3, is

(22)

t)

kt+1 = κ(btR , 0) = λbtR for t ∈ [0,

and the level of output per worker in period t + 1, yt+1 , as follows from (1) and (22), is45

yt+1 = A[λbtR ]α for t ∈ [0,

t).

(23)

The dynamics of output per worker. The evolution of output per Worker in Regime I

is driven in this regime by physical capital accumulation. The income of the Workers is not

sufficiently high to permit intergenerational transfers and therefore savings, and the evolution of

intergenerational transfers among Capitalists determines, therefore, the accumulation of physical

capital and thus the growth of output per worker over Regime I.

The evolution of the intergenerational transfers in the economy, as follows from (21) and

Lemma 3, are

⎫

R = ψ R (b R , 0) = max[β[w(λb R ) + b R R(λb R ) − θ], 0]

bt+1

⎬

t

t

t

t

for t ∈ [0,

t ),

(24)

⎭

P

bt+1 = 0

where b0R > 0 is given. Hence, in Regime I the dynamical system is fully determined by the

evolution of transfers across members of group R.

Hence, the evolution of the entire dynamical system in Regime I can be represented by

the evolution of output per worker. Since the aggregate income of the Capitalists (group R)

44. This assumption is designed to simplify the presentation of the results. As will become apparent, even if

Assumption A2 would be violated, the Capitalists would have an incentive to support the education of Workers.

45. Note that since the size of the population is 1, Yt+1 = yt+1 .

GALOR & MOAV

DAS HUMAN-KAPITAL

105