- 105 - by Lawrence W. Sherman University of Pennsylvania

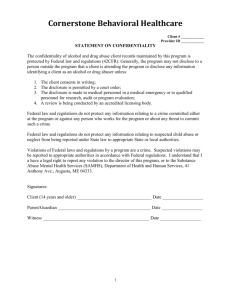

advertisement