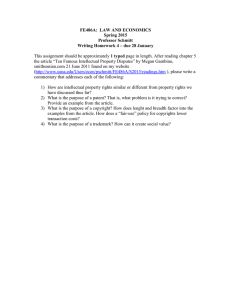

1600 I P :

advertisement