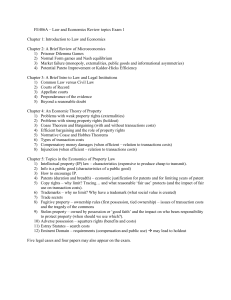

0740 T C RANSACTION

advertisement