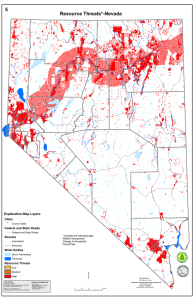

Wildfire Great Basin forum the search for solutions

advertisement