Document 12364236

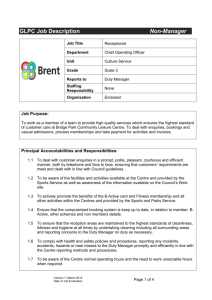

advertisement