Comparing latent class and dissimilarity based clustering for mixed type variables

advertisement

Comparing latent class and dissimilarity

based clustering for mixed type variables

with application to social stratification

Christian Hennig and Tim F. Liao∗

Department of Statistical Science, UCL,

Department of Sociology, University of Illinois

August 3, 2010

Abstract

Data with mixed type (metric/ordinal/nominal) variables can be clustered

by a latent class mixture model approach, which assumes local independence.

Such data are typical in social stratification, which is the application that

motivates the current paper. We explore whether the latent class approach

groups similar observations together and compare it to dissimilarity based

clustering (k-medoids). The design of an appropriate dissimilarity measure

and the estimation of the number of clusters are discussed as well, comparing

the BIC, average silhouette width and the Calinski and Harabasz index.

The comparison is based on a philosophy of cluster analysis that connects the problem of a choice of a suitable clustering method closely to the

application by considering direct interpretations of the implications of the

methodology. According to this philosophy, model assumptions serve to understand such implications but are not taken to be true. It is emphasised that

researchers implicitly define the “true” clustering and number of clusters by

the choice of a particular methodology. It is illustrated that even if there is a

true model, a clustering that doesn’t attempt to estimate this truth may be

preferable. The researcher has to take the responsibility to specify the criteria

on which such a comparison can be made. The application of this philosophy to data from the 2007 US Survey of Consumer Finances implies some

techniques to obtain an interpretable clustering in an ambiguous situation.

Keywords: mixture model, k-medoids clustering, dissimilarity design,

number of clusters, interpretation of clustering

∗

Research Report No. 308, Department of Statistical Science, University College London.

Date: August 2010.

1

1 INTRODUCTION

1

2

Introduction

In this paper we explore the use of formal cluster analysis methods for social stratification based on mixed type data with continuous, ordinal and nominal variables.

Two quite different approaches are compared, namely a latent class/finite mixture model for mixed type data (Vermunt and Magidson, 2002), in which different

clusters are modelled by underlying distributions with different parameters (mixture components), and a dissimilarity based approach not based on probability

models (k-medoids or “partitioning around medoids”, Kaufman and Rouseeuw,

1990) with different methods to estimate the number of clusters. The application

that motivated our work on mixed type data is social stratification, in which such

data typically arise (as in social data in general). The focus of this paper is on

the statistical side, including some general thoughts about the choice and design

of cluster analysis methods that could be helpful for general cluster analysis in

a variety of areas. Another publication in which the sociological background is

emphasized and discussed in more detail is in preparation.

The philosophy behind the choice of a cluster analysis method in the present paper

is that it should be driven by the way concepts like “similarity” and “belonging

together in the same class” are interpreted by the subject-matter researchers, and

by the way the clustering results are used.

This can be difficult to decide in practice. The concept of social class is central

to social science research, either as a subject in itself or as an explanatory basis

for social, behavioral, and health outcomes. The study of social class has a long

history, from the social investigation by the classical social thinker Marx to todays ongoing academic interest in issues of social class and stratification for both

research and teaching purposes (e.g., Grusky, Ku, and Szelnyi 2008). Researchers

in various social sciences use social class and social stratification as explanatory

variables to study a wide range outcomes health and mortality (Pekkanen et al.

1995) to cultural consumption (Chan and Goldthorpe 2007).

When social scientists employ social class or stratification as an explanatory variable, they follow either or both of the two common practices, namely using one

or more indicators of social stratification such as education and income and using

some version of occupation class, often aggregated or grouped into a small number

of occupation categories. For example, Pekkanen et al. (1995) compared health

outcomes and mortality between white-collar and blue-collar workers; Chan and

Goldthorpe (2007) analyzed the effects of social stratification on cultural consumption with a variety of variables representing stratification, including education, income, occupation classification, and social status (a variable they operationalized

themselves). The reason for researchers routinely using some indicators of social

class is simple: There is no agreed-upon definition of social class, let alone a specific

agreed-upon operationalization of it. Neither is the usage of social stratification

unified.

1 INTRODUCTION

3

Various different concepts of social classes are present in the sociological literature,

including a “classless” society (e.g., Kingston, 2000), society with a gradational

structure (e.g., Lenski, 1954) and a society in which discrete classes (interpreted in

various, but usually not data-based ways) are an unmistakable social reality (e.g.,

Wright, 1997).

The question to be addressed by cluster analysis is not to decide the issue eventually in favour of a certain concept, but rather to “let the data speak” concerning

the issues discussed in the literature. It is of interest whether clear clusters are apparent in data consisting of indicators of social class, but also how these data can

be partitioned in a potentially useful and interpretable way even without claiming that these classes are necessarily “undeniably real”; they may rather serve as

efficient reduction of the information in the data and as a tool to decompose and

interpret inequality. In this way, multidimensional manifestations of inequality can

be structured. A latent class model was proposed for this by Grusky and Weeden

(2008) and applied to (albeit one-dimensional) inequality data by Liao (2006). It

is also of interest how clusterings of relevant data relate to theoretical concepts

of social stratification applied to the data. A problem is that typically in data

used for social stratification there is no clear separation between clusters on the

metric variables, whereas categorical variables may create artificial gaps. Similar

data have been analysed by multiple correspondence analysis (e.g., Chapter 6 of

Le Roux and Rouanet, 2010), on which a cluster analysis can be based. This,

however, requires continuous variables to be categorised and seems more suitable

with a larger number of categorical variables.

A main task of the present paper is to relate the characteristic of different cluster

analysis methods to the subject matter. When comparing the methods, the main

focus is not whether the assumption of an underlying mixture probability model

is justified or not. Whereas such an assumption can probably not be defended,

the clustering outcomes of estimating latent class models may still make sense, depending on whether the underlying cluster concept is appropriate for the subject

matter (the present study is somewhat ambiguous about this question). The different methods are therefore compared based on the characteristics of their resulting

clusterings. “Model assumptions” are taken into account in order to understand

these characteristics properly, not in order to be verified or refuted. Important

characteristics are the assumption of “local independence” in latent class clustering (see Section 2) and the question whether the methods are successful in bringing

similar observations together in the same cluster.

In Section 2 latent class clustering is introduced. Section 3 discusses the philosophy

underlying the choice of a suitable cluster analysis methodology. Dissimilarity

based clustering requires a dissimilarity measure, the design of which is treated

in Section 4. Based on this, Section 5 introduces partitioning around medoids

along with some indexes to estimate the number of clusters. Section 6 presents a

comparative simulation study. In Section 7, the methodology is applied to data

from the US Survey of Consumer Finances and a concluding discussion is given in

4

2 LATENT CLASS CLUSTERING

Section 8.

2

Latent class clustering

This paper deals with the cluster analysis of data with continuous, ordinal and

nominal variables. Denote the data w1 , . . . , wn , wi = (xi , yi , zi ), xi ∈ IRp , yi ∈

O1 × . . . × Oq , zi ∈ C1 × . . . × Cr , i = 1, . . . , n, where Oj , j = 1, . . . , q are ordered

finite sets and Cj , j = 1, . . . , r are unordered finite sets.

A standard method to cluster such datasets is latent class clustering (Vermunt

and Magidson 2002), where w1 , . . . , wn are modelled as i.i.d., generated by a

distribution with density

f (w) =

k

X

h=1

πh ϕah ,Σh (x)

q

Y

j=1

τhj (yj )

r

Y

τh(q+j) (zj ),

(2.1)

j=1

where w = (x, y, z) is defined as wi above without subscript i. Furthermore

Pk

h=1 πh = 1, ϕa,Σ denotes the p-dimensional Gaussian density with mean vector

a and covariance matrix Σ (which may be restricted, for example to be a diagonal

P

P

matrix), and y∈Oj τhj (y) = z∈Cj τh(q+j)(z) = 1, πh ≥ 0, τhj ≥ 0∀h, j.

A way to use the ordinal information in the y-variables is to restrict, for j =

1, . . . , q,

exp(ηhjy )

, ηhjy = βjξ(y) + βhj ξ(y),

(2.2)

τhj (y) = P

u∈Oj exp(ηhju )

where ξ(y) is a score for the ordinal values y. This is based on the adjacent-category

logit model (see Agresti, 2002), as used in Vermunt and Magidson (2005). The

score can be assigned by use of background information, certain scaling methods

(see, e.g., Gifi, 1990), or as standard scores 1, 2, . . . , |Oj | for the ordered values

if there is no further information about ξ. In some sense, through ξ, ordinal information is used at interval scale level, as in most techniques for ordinal data.

Note that in (2.2) it is implicitly assumed that ordinality works by either increasing or decreasing monotonically the mixture component-specific contribution to

τhj (y) through βhj , which is somewhat restrictive. There are several alternative

approaches for modeling the effect of ordinality (see, e.g., Agresti, 2002), which

incorporate different restrictions such as a certain stochastic order of mixture components (Agresti and Lang, 1993). The latter is particularly difficult to justify in

a multidimensional setting in which components may differ in a different way for

different variables (or not at all for some).

The parameters of (2.1) can be fitted by the method of maximum likelihood (ML)

using the EM- or more sophisticated algorithms, and given estimators of the parameters (denoted by hats), points can be classified into clusters (in terms of

interpretation identified with mixture components) by maximising the estimated

5

3 SOME CLUSTERING PHILOSOPHY

posterior probability that observation wi had been generated by mixture component h under a two-step model for (2.1) in which first a mixture component

γi ∈ {1, . . . , k} is generated with P (γi = h) = πh , and then wi given γi = h

according to the density

fh (w) = πh ϕah ,Σh (x)

q

Y

τhj (yj )

j=1

r

Y

τh(q+j)(zj ).

j=1

Using this, the estimated mixture component or cluster for wi is

γ̂i = arg max π̂h fˆh (wi ),

(2.3)

h

where fˆh denotes the density with all parameter estimators plugged in. The number of mixture components k can be estimated by the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). All this is implemented in the software package LatentGOLD (Vermunt

and Magidson, 2005; note that its default setting include a certain pseudo-Bayesian

correction of the ML-estimator in order to prevent the likelihood from degenerating).

The meaning of (2.1) is that, within a mixture component, the continuous variable is assumed to be Gaussian, the discrete (ordinal and nominal) variables are

assumed to be independent from the continuous variables, and independent from

each other (“local independence”) and the ordinal variables are assumed to be

distributed as given in (2.2).

The question arises why it is justified to interpret the estimated mixture components as “clusters”. The model formulation apparently does not guarantee that

the points classified into the same mixture component are similar, which usually

is taken as a cluster-defining feature. In the following, we investigate this question

and some implications. This includes a discussion of the definition of “similarity”

in the given setup, and the comparison of latent class clustering with an alternative

similarity-based clustering method. (See Celeux and Govaert, 1991, for an early

attempt to relate latent class clustering to certain dissimilarities.)

3

Some clustering philosophy

The merit of the model-based view of statistics is not that it would be good

because the models really holded and that therefore the methods derived from

the model-based point of view as optimal (for example ML) were really the best

methods that could be used. Statisticians do not believe that the models are really

true, and although it is accepted that statistical models may fit the data better or

worse, and there is often a case to use a better-fitting model, it is misleading to

discuss model-based methodology as if it were crucial to know whether the model

is true. The models are rather used as an inspiration to find methodology that

6

3 SOME CLUSTERING PHILOSOPHY

1

2

3

4

x

5

6

7

6

2 2

4

5

222

22 2222

2

22222 2 222 2

222

552

2222 22 22222

5

2

5

5

5

2

2

5

5

2

5555

5

5

2

2

55

2 2

355555 2 2222222222 2222 22

33

33

8 2

333 5 2 22

8 888888

33

333

33

33

88 888 8 8

3333

3 333 3 888 888

3333

3

3

3

88

3333

1

33

88

8

1

1

1

8

8

8

1

8

1

8

8

1111

111

11111

77

8 88 88 8888 8

7777

7777

7

777

6666

7

77

111

7

7

1

8

7

8

7

7

7

7

1

77

7

7

7

7

7

7

6

8

77777777

66

77

777 666

7

7

7 666666666

8

44 66666

44

444

4

4

4

4

4

44

8

4

44

44

4 4

3

1

1

2

22

2

4

3

y

5

111

11 1111

3

11311 3 3

113

333 3

111

1111 33 3 333

1

33 3

1

1

3

1

3

1

1

1131

3

3

3

1

3 3

1

1111111 3 333333333 3333333

3

11

3

11

111 1 3 33

3 333333

11

111

11

11

33 333 3 3

1111

1 111 3 333 333

1111

1

1

1

11

33 3

1

1

1111111

3 3 3

111

111

11

11

33 33333333333 3

2

1

1

2

2

3

1

2

2

2

2

2

1

11111 11

222

22

2

2

2

2

2

3

2

3

2

2

2

2

22

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

3

22222222

11

22

222 111

2

2

2 111111111

3

11 11111

11

111

1

1

1

1

1

11

3

1

11

11

1 1

2

1

1 1

y

6

1

13

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

x

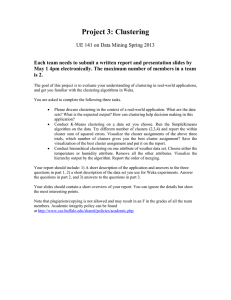

Figure 1: Artificial dataset from a 3-components Gaussian mixture (components

indicated on left side) with optimal clustering (right side) from Gaussian mixture

model according to the BIC with within-component covariance matrices restricted

to be diagonal.

otherwise would not have been found. But ultimately a model assumption is only

one of many possible aspects that help to understand what a statistical method

does. The ultimate goal of statistics cannot be to find out the true underlying

model, because chances are that such a model does not exist (the whole frequentist

probability setup is based on the idealisation of infinite repetition, and the Bayesian

approach uses similar idealisations through the backdoor of “exchangeability”, see

Hennig, 2009). Therefore, methodology that is not based on a statistical model

may compete with model-based methodology in order to analyse the same data,

as is the case in cluster analysis (for example, most hierarchical agglomerative

methods such as complete linkage are not based on probability models).

The idea of “true clusters” is similarily misleading as the idea of the “true underlying model”. Neither the data alone, nor any model assumed as true can determine

what the “true” clusters in a dataset are. This is always dependent on what the

researchers are looking for, and on their concept of “belonging together”. This

can be nicely illustrated in the case of the Gaussian mixture model (the latent

class model (2.1) above with q = r = 0). The left side of Figure 1 shows a mixture of three Gaussian distributions with p = 2. Of course, in some applications,

it makes sense here to define the appropriate number of clusters as 3, with the

mixture components corresponding to the clusters. However, if the application

is social stratification, and the variables are income and some status indicator,

for example, this is not appropriate, because it would mean that the same social

stratum (interpreted to correspond to mixture component no. 1) would contain

the poorest people with lowest status as well as the richest people with the highest

3 SOME CLUSTERING PHILOSOPHY

7

status. The cluster concept imposed by the Gaussian mixture model makes a certain sense, but it does not necessarily bring the most similar observations together,

which, for some applications, may be inappropriate even if the Gaussian mixture

model were true (more examples for this can be found in Hennig, 2010). Gaussian

mixtures are very versatile in approximating almost any density, so that it is in

fact almost irrelevant whether data have an obvious “Gaussian mixture shape” in

order to apply clustering based on the Gaussian mixture model. The role of the

model assumption in cluster analysis is usually (apart from some special applications in which the models can be directly justified) not about the connection of

the model to the “truth”, but about formalising what kind of cluster shape the

method implies.

One alternative to fitting a fully flexible Gaussian mixture is to assume a model

in which all within-component covariance matrices are assumed to be diagonal

matrices, i.e., the (continuous) variables are assumed to be locally independent.

This gives more sensible clusters for the dataset of Figure 1 (see right side) for

social stratification, because clusters could no longer be characterised by features

of dependence (“income increases with status” for cluster no. 1, comprising low

income/low status as well as high income/high status) even though we know that

this model is wrong for the simulated dataset. It still does not guarantee that

observations are always similar within clusters, because variances may still differ

between components, see Figure 1. One may argue that covariance matrices should

be even stronger restricted (for example to be equal across components), but this

may be too restrictive for at least some uses of social stratification, in which one

would want to distinguish very special distinctive classes (with potentially small

within-classes variation) from more general classes with larger variation. Without

claiming that “diagonal covariance matrices” are the ultimatively best approach,

we stick to it here (but present a non-model-based alternative later). Another

reason for this is that it extends the local independence assumption for ordinal and

nominal variables in the latent class model (2.1) to continuous variables. Actually,

local independence is the only component-defining assumption in that model for

nominal variables.

As a side remark, it was already noted in Section 2 that (2.2) is restricted and does

not allow density peaks in the middle of the order in the component-specific part.

The problem with this is not that (2.2) therefore cannot fit the true distributions

of ordinal data (actually, ordinality is a feature of their interpretation, not of their

distribution), but it seems to be too restrictive to fit a certain natural (though

not unique) concept of how an ordinality based cluster should look like (although

potential remedies for this are not the topic of the current paper).

Assuming a mixture of locally independent distributions for nominal data basically means that latent class clustering decomposes dependences between nominal

variables into several clusters within which there is independence. Considering the

right panel of Figure 1 (our intuition about “clusters” is usually shaped by Euclidean variables), this could make some sense, although it cannot be taken for

8

1.5e+07

16

14

log income

1.0e+07

10

333

333333

333

3333

3

3

3333

333

33

33

33333

333

3

33333

3

12

1 1 111 11

1 11 111111 1

111111111

11

11111111111111

1111

1111111

1111

11 11

1111111

111

111

111 11111111 1 1

11111

1

11

111111

1

111

11111111

11

1 11 1

11

111111111111111

1

1

1 1111 11 111

111 1

5

10

x

15

0.0e+00

5

y

income

10

2

5.0e+06

15

22

222

2 22 222 2222

22

2 22 222222222

222 22222 222

222 2 2

2222 222 2

222

22 2

2

2

2

2

2

2 22 22222 222 2

2

2

2 2 2 22

2

2

18

3 SOME CLUSTERING PHILOSOPHY

0e+00

1e+06

2e+06

3e+06

savings amount

4e+06

5e+06

5

10

15

log savings amount

Figure 2: Left side: artificial dataset from a 3-components Gaussian mixture.

Middle: subset of data from US Survey of Consumer Finances 2007 (some outliers

are outside the plot range and are not shown because they would dominate the

plot too much). Right side: same dataset with log-transformed variables (all

observations shown).

granted that within-cluster dissimilarity will be small (dissimilarity based clusterings of this dataset are shown in Figure 3). An advantage of the local independence assumption in terms of interpretation is that it makes sure that clusters

can be interpreted by interpreting the within-cluster marginal distributions of the

variables alone, which determine the component-wise distributions. Finding out

whether the mixture components in a latent class model bring together similar

observations requires the definition of dissimilarity between them, which is done

in Section 4.

Often in cluster analysis it is required to estimate the number of clusters k. In the

latent class cluster model (2.1), this can be done by the BIC, which penalises the

loglikelihood for every k with 12 log(n) times the number of free parameters in the

model. It can be expected that the BIC estimates k consistently if the model really

holds (though as far as we know this is only proven for a much simpler setup, see

Keribin 2000). If the model does not hold precisely, it is quite problematic to use

such a result as a justification of the BIC, because the true situation may be best

approximated by very many, if not infinitely many, mixture components if there

are only enough observations, which is not of interpretative value.

In general, the problem of estimating the number of clusters is notoriously difficult.

It requires a definition of what the true clusters are, which looks straightforward

only if there is a simple enough true underlying model such as (2.1), and it has

been illustrated above that even in this case it is not as clear as it seems to

be. It generally depends on the application; sometimes clusters are required to

be separated by gaps the size of which depends on the application, sometimes

clusters are not allowed to contain large within-cluster dissimilarities, in some

applications it is required that clusterings remain stable under small changes of the

data, but this is unnecessary in other applications. Sometimes the idea of “truth”

3 SOME CLUSTERING PHILOSOPHY

9

is connected to the idea of an unobservable true underlying model, sometimes it is

connected to some external information, and sometimes “truth” is only connected

to the observable data.

Unfortunately, up to now, the vast majority of the literature is not explicit enough

about the connection of any cluster analysis method and any method to estimate

the number of clusters to the underlying cluster concept to be decided by the

researcher. Deciding about a criterion to “estimate” the true number of clusters

often actually rather means defining this number. Most such criteria can be expected to give a proper estimate in situations that seem intuitively absolutely clear

(see the left side of Figure 2; all methods discussed in the present paper yield the

same clustering with k = 3 for this dataset), but in social stratification datasets

far more often are so complex that there is no clear clustering that immediately

comes to mind when looking at the data, in this sense supporting the idea of

a gradational structure of society. In the middle (and on the right side, in logtransformed form) of Figure 2, only two variables from a (random) subset of data

from the US Survey of Consumer Finances 2007 are shown; assume that social

strata should be somewhat informative, so there should probably be two or more

of them even if there are no clear “gaps” in the data. However, it is illusory, at

least for two-dimensional data, to expect that a formal cluster analysis method can

reveal clearer grouping structure than what our eyes can see in such a plot. If, as

on the middle or right side of Figure 2, k cannot be determined easily by looking

at the graph, it can be expected that criteria to estimate k run into difficulties as

well and may come up with a variety of numbers. For higher dimensional data, of

course it is possible that a clearer grouping structure exists than what can be seen

in two-dimensional scatterplots of the data, but generally it cannot be taken for

granted that a clear and more or less unique grouping can be found. Therefore the

researchers have to live with the situation that different methods can produce quite

different clustering solutions without clearly indicating which one is best. Some

researchers may believe that using a formal criterion to determine the number of

clusters is more “objective” and therefore better than fixing it manually, but this

only shifts subjectivity to the decision about which criterion to use.

Most criteria to estimate the number of clusters can only be heuristically motivated. The penalised likelihood used in the BIC seems to be reasonable for

theoretical reasons in such cases, but it is quite difficult to understand what its

implications are in terms of interpretation, and why its exact definition should be

in any sense optimal. There are certain dissimilarity-based criteria (see Sections 5

and 6) that may be seen as more directly appealing, but any of these may behave

oddly in certain situations. Usually, they are only convincing for comparisons over

a fairly limited range for values of k and may degenerate for too large k (and/or

k = 1), so that the researcher should make at least a rough decision about the

order of magnitude k should have for the given application (if mixture models are

to be applied, one may also use a prior distribution over the numbers of clusters

in a Bayesian approach; such a prior would then not be about “belief” but rather

4 DEFINING DISSIMILARITY

10

about “tuning” the method in order to balance desired numbers of clusters against

“what the data say”). In some situations in which formal and graphical analysis

suggests that it is illusory to get an objective and well justified estimation of the

number of clusters, this may be an argument to fix the number of clusters at some

value roughly seen to be useful, even though there is no strong subject-matter

justification for any particular value. Note that usually the literature implies that

fixing the number of clusters means that their true value is known for some reason,

but in practice the difficult problem of estimating this number is often avoided (or

done in a far from convincing way) even if there are no strong reasons for knowing

the number.

A particular difficulty with mixed type data is that the standard clustering intuition of most people is determined by the idea of “clumps” and “separation” in

Euclidean space, but this is inappropriate for discrete ordinal and nominal data.

Such data can in principle be represented in Euclidean space (standard scores can

be used for ordinal variables, and nominal variables can be decomposed into one

indicator variable for each category, so that no inappropriate artificial quantitative information is added). But if this is done, there are automatically “clumps”

and“gaps”, because the observations clump on the (usually small) number of admissible values (see, for example, Figures 4 and 5). Whereas in principle such

data can still be analysed using Gaussian mixtures or other standard methods for

Euclidean data, the discreteness may produce clustering artifacts.

This makes it difficult to have a clear intuition about what clustering means for

discrete data. The “local independence”-assumption in latent class clustering looks

attractive because it at least yields a clear formal description of a cluster, which,

however, may not agree with the aim of the researcher.

In conclusion, the researchers should not hope that the data will tell them the

“objectively true” clustering if they only choose the optimal methodology, because

the choice of methodology defines implicitly what the true clusters are. Therefore,

this choice requires several decisions of the researchers on how to formalise the

aim of clustering in the given application. In social stratification, the researchers

cannot expect the data to determine what the true social strata are, but they

need to define first how social strata should be diagnosed from the data (what

“dissimilarity” means, and what the underlying cluster concept is).

4

Defining dissimilarity

In order to discuss whether or not latent class clustering (or any other clustering

method) puts similar observations together into the same cluster, a formal definition of “dissimilarity” is needed (dissimilarity measures are treated as dual to

similarity measures here).

As the choice of the clustering method, this is a highly nontrivial task that depends

on decisions of the researcher, because the measure should reflect what is taken as

11

4 DEFINING DISSIMILARITY

“similar” in a given application (see Hennig and Hausdorf, 2006, for some general

discussion of dissimilarity design).

The crucial task for mixed type data is how to aggregate and how to weight the

different variables against each other. Variable-wise dissimilarities can be aggregated for example in a Euclidean or in a Gower/Manhattan-style. The Euclidean

distance between two objects xi , xj on p continuous variables xi = (xi1 , . . . , xip )

and analogously for j is defined as

v

u p

uX

dE (xi , xj ) = t (xil − xjl )2 =

l=1

v

u p

uX

t

dl (xil , xjl )2 ,

l=1

where dl is the standard dissimilarity (absolute value of the difference) on variable

l. The so-called Gower distance (Gower, 1971) aggregates mixed type variables

in the same way as the Manhattan or L1 -distance aggregates continuous variables

variables:

p

dG (xi , xj ) =

X

dl (xil , xjl ).

l=1

Variable weights wl can easily be incorporated in both aggregation schemes by

multiplying the dl with constants depending on l, which is equivalent to multiplying

the variables by wl .

Although dG seems to be the more direct and intuitive aggregation method (at

least if standard transformations of Euclidean space such as rotations do not seem

to be meaningful because of incompatible meanings of the variables) and was

recommended by Gower for mixed type data, there is an important advantage of

dE for datasets with many observations and not so many variables, as are common

in social stratification. Many computations for Euclidean distances (such as the

clara clustering method and the Calinski and Harabasz index, see Section 5) can

be computed directly from the “observations ∗ variables”-matrix and do not need

the handling of an (often too large) full dissimilarity matrix. Therefore Euclidean

aggregation is preferred here. The following discussion will be in terms of the

variables, which are then aggregated as in the definition of dE .

The definition of dE can be extended to mixed type variables in a similar way in

which Gower extended dG . Ordinal variables can be used with standard scores. Of

course, alternative scores can be used if available. An alternative that preserves

the ordinal nature of the data but is often dubious in terms of interpretation is

to rank the variable values so that mean ranks are used for ties. This introduces

larger dissimilarities between neighbouring categories with many observations than

between neighbouring categories with few observations. It depends on the application whether this is suitable, but it runs counter to the intuition behind clustering

to some extent, because it introduces large dissimilarities between “densely populated” sets of neighbouring categories, which may be regarded as giving rise to

clusters.

4 DEFINING DISSIMILARITY

12

The different values of a nominal variable should not carry numerical information,

and therefore nominal variables should be replaced by binary indicator variables

for all their values (let mj denote the number of categories of variable j; technically

only mj − 1 binary variables would be needed to represent all information, but in

terms of dissimilarity definition, leaving one of the categories out would lead to

asymmetric treatment of the categories).

The variables then need to be weighted (or, equivalently, standardised by multiplying them with constant factors; adding constants to “center” variables can

be done as well but is irrelevant for dissimilarity design) in order to make them

comparable for aggregation. There are two aspects of this, the statistical aspect

(the variables need to have comparable distributions of values) and the substantial aspect (subject matter knowledge may suggest that some variables are more or

less important for clustering). For most of the rest of this section, the substantive

aspect is ignored, but it should not be forgotten that after applying the following

considerations for statistical reasons, further weighting factors can be incorporated

for substantive reasons (a subtle example is given in Section 7), and it will also

turn out that the two aspects cannot be perfectly separated.

Before weighting, it also makes sense to think about transformations of the continuous variables. The main rationale for transformation in the philosophy adopted

here is that transformation makes sense if distances on the transformed variable

reflect better the “interpretative distance” in terms of the application between

cases. It is for example not the aim of transformation here to make data “look

more normal” for the sake of it, although this sometimes coincides with a better

reflection of interpretative distances.

For example, for the variables giving income and savings amount in the middle of

Figure 2, log-transformations were applied (right side of Figure 2). The distributional pattern of the transformed data looks somewhat more healthy to statisticians (and there are no outliers dominating the plot anymore, as there were in the

untransformed variables), but the main argument for the transformation is that in

terms of social stratification, it makes sense to allow proportionally higher variation within high-income and/or high-savings clusters; the interpretative difference

between two people with yearly incomes of $2m and $4m is not clearly larger than

but rather equal to the interpretative difference between $20,000 and $40,000. Of

course, transformations like log(x + 1) may be needed to deal with zeroes in the

data, and researchers should feel encouraged to come up with more creative ideas

(such as piecewise linear transformations to compress some value ranges more than

others) if these add something from the “interpretative” subject-matter perspective. Transformations that are deemed sensible for dissimilarity definition should

also be applied before running latent class/Gaussian mixture clustering.

There are various ways of standardisation to make the variation of continuous

variables comparable, which comprise for example

• range standardisation (for example to [0, 1]),

4 DEFINING DISSIMILARITY

13

• standardisation to unit variance,

• standardisation to unit interquartile range (or median absolute deviance).

The main difference here is how the methods deal with extreme observations. A

major disadvantage of range standardisation is that this is governed by the two

most extreme observations, and in presence of outliers this can mean that pairwise

differences on such a variable between a vast majority of observations could be

approximately zero and only the outliers are considerably far away from the rest.

This is problematic if valuable structure (in terms of the interpretation) is expected

among the non-outliers. On the other hand, range standardisation guarantees that

the maximum within-variable distances are equal over all variables.

The opposite is to use a robust statistic for standardisation such as the interquartile

range, which is not affected by extreme outliers. This has a different disadvantage

in presence of outliers, because if there are extreme outliers on a certain variable, the distances between these outliers and the rest of the observations on this

variable can still be very large and outliers on certain variables may dominate distances on other variables when aggregating. In the present paper standardisation

to unit variance is adopted, which is a compromise between the two approaches

discussed before. Variable-wise extreme outliers are problematic under any approach, though, and it is preferable to handle them by transformation in advance

(Winsorising, see Tukey 1962, may help).

Categorical variables have to be standardised so that the variable-wise distances

between their levels are properly comparable to the distances between observations

on continuous variables with unit variance.

Nominal variables are discussed first. Assume that for a single original nominal variable there are two variables in the dataset, namely the dummy indicator variables for both levels (as discussed above, this is necessary for symmetric treatment of categories for general nominal variables, although it would

not be necessary for binary variables). E(X1 − X2 )2 = 2 holds for i.i.d. random variables X1 , X2 with variance 1. For an originally nominal variable with

I categories, let Yij , i = 1, . . . , I, be the value of observation j on dummy

variable i. A rationale to standardise the dummy variables Yi is to achieve

PI

2

2

some factor q. The rationale

i=1 E(Yi1 − Yi2 ) = qE(X1 − X2 ) = 2q with

P

for this is that in the Euclidean distance dE , Ii=1 (Yi1 − Yi2 )2 is aggregated with

(X1 − X2 )2 . It may seem natural to set q = 1, so that the expected contribution

from the nominal variable equals, on average, the contribution from continuous

variables with unit variance. However, if the resulting dissimilarity is used for

clustering, there is a problem with q = 1, namely that, because of the fact that

the distance between two identical categories is zero, it makes the difference between two different levels of the nominal variable (potentially much) larger than

E(X1 − X2 )2 , and therefore it introduces wide gaps (i.e., subsets between which

there are large distances), which could force a cluster analysis method into identifying clusters with levels of the categorical variable too easily. Therefore we rather

14

4 DEFINING DISSIMILARITY

recommend q = 12 , though larger values can be chosen if it is deemed, in the

given application, that the nominal variables should carry higher weight. A small

comparison can be found in Section 6.3.

q = 12 implies that, for an originally binary variable for which the probability of

both categories is about 12 (which implies that the number of pairs of observations

in the same category is about equal to the number of pairs of observations in

different categories), the effective distance between the two categories is about equal

to E(X1 − X2 )2 = 2 (and correspondingly lower for variables with more than two

categories).

There is another consideration regarding the standardisation of the Yi -variables so

that

I

X

i=1

!

E(Yi1 − Yi2 )2 = 2q.

(4.1)

(Yi1 −Yi2 )2 can only be 0 or 1 for dummy variables, but the expected value depends

on the category probabilities. As a default, for standardisation these can be taken

to be I1 for each category. An obvious alternative is to estimate them from the

data. However, it may not be desired that the effective distance between two

categories depends on the empirical category distribution in such a way; it would

for example imply that the distance between categories would be much larger for

a binary variable with only a very small probability for one of the categories.

Whether this is appropriate can again only be decided taking into account the

meaning and interpretative weight of the variables.

For ordinal variables Y with standard coding and I categories, we suggest

!

E(Y1 − Y2 )2 = 2q, q =

1

1 + 1/(I − 1)

(4.2)

as rationale for standardisation, which for binary variables (I = 2; for binary

variables there is no difference between ordinal and nominal scale type) yields the

same expected variable-wise contribution to the Euclidean distance as (4.1), and

q → 1 for I → ∞ means that with more levels the expected contribution converges

toward that of a continuous variable. The same considerations as above hold for

the computation of the expected value.

To summarise, the overall dissimilarity used here is defined by

• Euclidean aggregation of variables,

• suitable transformation of continuous variables,

• standardisation of (transformed) continuous variables to unit variance,

• using I dummy variables for each nominal variable, standardised according

to (4.1) with q = 21 ,

15

5 DISSIMILARITY BASED CLUSTERING

• using standard coding for each ordinal variable, standardised according to

(4.2),

• additional weighting of variables according to subject matter requirements.

5

Dissimilarity based clustering

A dissimilarity based clustering method that is suitable as an alternative to latent class clustering for social stratification data is “partitioning around medoids”

(Kaufman and Rouseeuw, 1990). This is implemented as function pam in the addon package cluster for the software system R (www.r-project.org). This is

based on the full dissimilarity matrix and may therefore require too much memory

for large datasets (n ≈ 20, 000 as in the example dataset in Section 7 is quite typical for social stratification examples). “Clustering large applications” (function

clara in cluster) is an approximative version for Euclidean distances that can

be computed for much larger datasets.

There are many alternative dissimilarity based clustering methods in the literature

(see, e.g., , for example Kaufman and Rouseeuw, 1990, Gordon, 1999) the classical

hierarchical ones such as single or complete linkage, but most of these require full

dissimilarity matrices and are unfeasible for too large datasets.

pam and clara minimise (approximately), for a dissimilarity measure d, the objective function

n

g(w1∗ , . . . , wk∗ ) =

X

i=1

min

j∈{1,...,k}

d(wi , wj∗ )

(5.1)

by choice of k medoids w1∗ , . . . , wk∗ from w. Note that this is similar to the popular k-means clustering, but somewhat more flexible in terms of cluster shapes and

more robust by using d instead of d2 (see Kaufman and Rouseeuw, 1990, although

gross outliers could still cause problems and should rather be handled using transformations in the definition of dissimilarity) and more appropriate for mixed type

data because the medoids are not, as in k-means, computed as mean vectors, but

are required to be members of the dataset, so no means are computed for nominal

and ordinal categories. The difference is illustrated in Figure 3. pam was used here

instead of clara because the dataset is small enough to make this computationally

feasible. The pam and k-means clustering (both with number of clusters optimized

by the CH-criterion between 2 and 9, see below) are similar (which they are quite

often), but cluster 8 in the k-means solution seems to include too many points

from the diagonal mixture component, causing a big gap within the cluster. The

corresponding pam cluster 4 only contains one of these points. This happens because the pam criterion can tolerate larger within-cluster dissimilarities in cluster

5 (corresponding to cluster 7 in the k-means solution), and because a single point

from the diagonal component has such an influence on the cluster mean (but not

on the cluster medoid) that further points are included under k-means.

16

5 DISSIMILARITY BASED CLUSTERING

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

6

4 4

4

5

444

44 4444

64444 4 444 4 4

666

666

6666 45 44545

6

55

666666

5

66666 655 555

66666666 66655555555 5555555

2

22

555 5

22

2222 6 6 66

6 3555555

22

2222

22

2

2

2

2

5 5

3

3

2

2

2

2222222

3

3

3

2

2

2

33 3

3

2

2

22

212

111

3 3 3

111

111

12

1

11

33 33333333333 3

8

1

1

8

8

3

8

1

8

8

8

8

1

11111 11

88

88

8

888

8

8888

3 3 3

8

8

88

88

1

888

88

88

88

888

888 1111

8

8

88

8 8888111

111

3

88 88888

8

77

777777

777

3

7

77

7

7

7 7

3

1

5

4

44

2

4

3

y

5

222

22 2222

2

22222 2 228 8

22

666

66262 22 22828

6

88 8

6

6

6

8

8

6

6

6666

8

8

6

6

8 8

6

6666666 6 688888888 8888 88

33

33

8 8

333 6 6 66

6 888888

33

333

33

33

99 988 9 8

3333

3 333 3 696 999

3333

3

3

3

31

99

1

1

33

99

9

1

1

1

9

9

9

1

9

1

9

9

1111

1111

44

9 99 99 9999 9

4444

444

4

444

777711111

4

44

111

4

4

9

4

9

4

4

4

4

1

44

4

4

4

4

4

7

4

9

44444444

77

44

444 777

4

4

4 777777777

9

45577777

55

55

5

5

5

5

5

55

9

5

55

55

5 5

2

1

2 2

y

6

2

22

7

1

2

3

x

4

5

6

7

x

Figure 3: Artificial dataset with pam clustering with k = 9 (left side) and 8means clustering (right side), number of clusters chosen optimally according to

the CH-criterion for both methods.

There are several possibilities to estimate the number of clusters for clara. Some of

them are listed (though treated there in connection to k-means) in Sugar and James

(2003); an older but more comprehensive simulation study is given in Milligan and

Cooper (1985). Taking into account the discussion in Section 3, it is recommended

to use a criterion that allows for direct interpretation and cannot only be justified

based on model-based theory. In the present paper, three such criteria are used:

Average Silhouette Width (ASW) (Kaufman and Rousseeuw, 1990). For a

b(i,k)−a(i,k)

be the

partition of w into clusters C1 , . . . , Ck let s(i, k) = max(a(i,k),b(i,k))

so-called “silhouette width”, where

a(i, k) =

X

1

1 X

d(wi , wj ), b(i, k) = min

d(wi , wj )

Cl 6∋wi |Cl |

|Ch | − 1 w ∈C

w ∈C

j

j

h

for wi ∈ Ch . The ASW estimate kASW maximises

1

n

l

Pn

i=1 s(i, k).

The rationale is that b(i, k) − a(i, k) measures how well chosen Ch is as a

cluster for wi . If, for example, b(i, k) − a(i, k) < 0, wi is further away,

on average, from the observations of its own cluster Ch than from those of

the cluster Cl 6∋ wi minimising the average dissimilarity from wi . A gap

between two clusters would make b(i, k) − a(i, k) large for the points of these

clusters, whereas splitting up a homogeneous data subset could be expected

to decrease b(i, k) stronger than a(i, k).

Calinski and Harabasz index (CH) (Calinski and Harabasz, 1974). The CH

17

5 DISSIMILARITY BASED CLUSTERING

estimate kCH maximises the CH index

W(k) =

Pk

B(k) =

B(k)(n−k)

W(k)(k−1) ,

1 P

wi ,wj ∈Ch

h=1 |Ch |

1 Pn

2

i,j=1 d(wi , wj )

n

where

d(wi , wj )2 ,

and

− W(k).

In the original definition, assuming Euclidean distances, B(k) is the betweencluster means sum of squares and W(k) is the within-clusters sum of squared

distances from the cluster means. The form given here is equivalent but can

be applied to general dissimilarity measures.

The index is attractive for direct interpretation because in clustering it is

generally attempted to get the between-cluster dissimilarities large and the

within-cluster dissimilarities small at the same time. These need to be properly scaled in order to reflect how they can be expected to change with k.

This index was quite successful in the simulations of Milligan and Cooper

B(k)(n−k)

(1985), which indicates that W(k)(k−1)

, derived from a standard F-statistic,

is a good way of scaling. However, it should be noted that using squared

dissimilarities in the index makes its use together with clara look somewhat

inconsistent; it is more directly connected to k-means. As far as we know, it

is not discussed in the literature how to scale a ratio of unsquared betweencluster and within-cluster dissimilarities in order to estimate the number of

clusters, and even if this could be done properly, another reason in favour

of CH is that it can be more easily computed for large datasets because a

complete dissimilarity matrix is not required and CH can be easily computed

from the overall and within-cluster covariance matrices. Furthermore, Milligan and Cooper (1985) used the index with various clustering methods some

of which were not based on squared dissimilarities.

Pearson version of Hubert’s Γ (PH) The PH estimator kΓ maximizes the Pearson correlation ρ(d, m) between the vector d of pairwise dissimilarities and

the binary vector m that is 0 for every pair of observations in the same

cluster and 1 for every pair of observations in different clusters. It therefore

measures, in some sense, how good the clustering is as an approximation

of the dissimilarity matrix. This is not exactly what is of interest in social

stratification, and therefore this criterion will not be used directly for estimating the number of clusters here, but will serve as an external (though

not exactly “independent”) criterion to compare the solutions yielded by the

other approaches.

Hubert’s Γ (Baker and Hubert 1975) was originally defined in a way similar to the above definition, but with Goodman and Kruskal’s rank correlation coefficient Γ instead of the Pearson correlation. The Pearson version

(as proposed under the name “Normalized Γ” in Halkidi, Batistakis and

Vazirgiannis, 2001) is used here, because it is computationally demanding

to compute the original version for even moderately large datasets (n > 200

or so). A side effect of using the Pearson version is that large dissimilarities

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

18

within clusters are penalised more, but it is affected more by outliers than

the original version.

Although the problem is clearest with CH, none of the three indexes is directly

connected to the clara objective function (for example by adding a penalty term

to it, as the BIC does with the loglikelihood). There is a certain tradition in

non-model based clustering and cluster validation of using indexes for estimating

the number of clusters that are not directly connected to the clustering criterion

for fixed k. One could argue against that by saying that if an index formalises

properly what the researcher is interested in, it should be optimal to optimise

this index for both given k and over a range of different values of k. However,

one could also argue that if the aim of the study is somewhat imprecise (as in

social stratification), having something that was obtained based on combining two

different (but reasonable) criteria could be more trustable (cf. the two clusterings

in Figure 3). Also, optimisation over a huge number of possible partitions is more

difficult than optimisation over a small number of admissible values for k, and on

the other hand it is much more complicated to obtain theoretical results about

estimating k than about clustering with fixed k, so what is good for one of these

tasks is not necessarily suitable for the other one.

Note that all three indexes could be distorted by gross outliers, which therefore

need to be handled by transformation in the definition of the dissimilarities. It also

has to be pointed out that all three indexes do not apply to k = 1, which means that

they estimate k ≥ 2. Assuming that the use that is made of social stratification

requires that there are at least two strata, this is not a problem. A strategy to

distinguish a homogeneous dataset from k ≥ 2 applicable with any index is to

simulate 1000 datasets, say, of size n, from some null distribution (for example

a Gaussian or uniform, potentially categorical or independent mixed continuouscategorical distribution), cluster them with k = 2 fixed, and estimate k = 1 if the

observed index value for k = 2 is below the 95% quantile of the simulated index

values, assuming implicitly that if in fact k > 2, k = 2 can already be expected to

give a significant improvement compared to k = 1.

6

6.1

A simulation study

Data generating models

In order to compare latent class clustering and clara (in the version defined above),

a simulation study with eight different data generating models was carried out. In

the study, we focused on models with continuous and nominal variables only. For

the generation of datasets it is irrelevant whether the interpretation of the levels of

categorical variables is nominal or ordinal, but the clustering methods were applied

so that categorical variables were treated as nominal. The reason for this is that

the potential for designing data generating models with potentially informative

19

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

simulation outcomes is vast. Therefore it seemed to be reasonable to suppress the

complication added by investigating mixing of three types of variables, which will

be a topic of further research, in order to rather understand certain situations in

detail than to cover everything superficially.

Data were generated according to (2.1) with different choices of parameters defining

the eight different models.

Further restrictions were made. There were always two continuous variables, and

with the one exception of M7, only one of the continuous variables (X1) was informative about the mixture components, whereas the other variable (X2) was

distributed according to a standard Gaussian distribution in all mixture components. Only one number of observations was simulated for each model, and the

numbers of observations were, for computational reasons, generally smaller than

those met in typical social stratification data.

Below, for component h, nh denotes the number of observations, and µh and σh2

denote the mean and variance of X1.

M1 - 2 components clearly separated in Gaussian variables, for each of them 2

components clearly separated in categorical variables.

Component 1 n1 = 150 , µ1 = 0, σ12 = 2.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Z3

1

0.8

0.4

0.8

Levels

2

3

0.1 0.1

0.2 0.2

0.1 0.1

4

0

0.2

0

Component 2 n2 = 100 , µ2 = 0, σ22 = 2.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Z3

1

0

0.2

0

Levels

2

3

0.1 0.1

0.2 0.2

0.1 0.1

4

0.8

0.4

0.8

Component 3 n3 = 200 , µ3 = 5, σ32 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 1.

Component 4 n4 = 100 , µ4 = 5, σ42 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 2.

M2 - 2 components clearly separated in Gaussian variables, for each of them 2

components not so clearly separated in categorical variables.

20

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

Component 1 n1 = 150 , µ1 = 0, σ12 = 2.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Z3

1

0.5

0.4

0.4

Levels

2

3

0.2 0.2

0.2 0.2

0.2 0.2

4

0.1

0.2

0.2

Component 2 n2 = 100 , µ2 = 0, σ22 = 2.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Z3

1

0.2

0.2

0.2

Levels

2

3

0.1 0.2

0.2 0.2

0.2 0.2

4

0.5

0.4

0.4

Component 3 n3 = 200 , µ3 = 5, σ32 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 1.

Component 4 n4 = 100 , µ4 = 5, σ42 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 2.

M3 - 2 overlapping components in Gaussian variables, for each of them 2 components not clearly separated in categorical variables. As M2, but with

σ12 = σ22 = 3, σ32 = σ42 = 2.

M4 - 2 components clearly separated in Gaussian variables, for each of them 2

components not so clearly separated in categorical variables, with 6 categorical variables.

Component 1 n1 = 150 , µ1 = 0, σ12 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Z3

Z4

Z5

Z6

1

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.5

0.4

0.25

Levels

2

3

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.25 0.25

4

0.1

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.2

0.25

Component 2 n2 = 100 , µ2 = 0, σ22 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables:

21

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Z3

Z4

Z5

Z6

1

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.25

Levels

2

3

0.1

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.25 0.25

4

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.5

0.4

0.25

Component 3 n3 = 200 , µ3 = 5, σ32 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 1.

Component 4 n4 = 100 , µ4 = 5, σ42 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 2.

M5 - 4 strongly overlapping components in Gaussian variables, with supporting

information from single categorical variable.

Component 1 n1 = 150 , µ1 = 0, σ12 = 3.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

1

0.9

Levels

2

3

0.05 0.05

4

0.1

Component 2 n2 = 100 , µ2 = 1, σ22 = 3.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

1

0.1

Levels

2

3

0.8 0.1

4

0

Component 3 n3 = 200 , µ3 = 4, σ32 = 2.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

1

0

Levels

2

3

0.05 0.05

4

0.9

Component 4 n4 = 100 , µ4 = 5, σ42 = 2.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

1

0.1

Levels

2

3

0 0.8

4

0.1

M6 - 3 components in Gaussian variables, two of which are far away from each

22

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

other, but with large variance component in between, for each of them 2

components not clearly separated in categorical variables.

Component 1 n1 = 150 , µ1 = 0, σ12 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

1

0.9

0.4

Levels

2

3

0.05 0.05

0.2

0.2

4

0

0.2

Component 2 n2 = 150 , µ2 = 0, σ22 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

1

0.2

0.1

Levels

2

3

0.2 0.2

0.7 0.1

4

0.4

0.1

Component 3 n3 = 150 , µ3 = 6, σ32 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 1.

Component 4 n4 = 150 , µ4 = 6, σ42 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

1

0.2

0.1

Levels

2

3

0.2 0.2

0.1 0.7

4

0.4

0.1

Component 5 n5 = 50 , µ5 = 3, σ52 = 4.

Distributions of categorical variables as in Component 1.

Component 6 n6 = 50 , µ6 = 3, σ62 = 4.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

1

0.2

0.1

Levels

2

3

0.2 0.2

0.1 0.1

4

0.4

0.7

M7 - 6 components with non-diagonal covariance matrices, i.e., X1 and X2 dependent.

n1 , . . . , n6 , µ1 , . . . , µ6 and the distributions of the categorical variables are

as in M6. The means of X2 are 0 in every component. The covariance

!

1 0.8

2

matrix for X1 and X2 in component h is σh Σ, where Σ =

,

0.8

1

σ12 = σ22 = 0.5, σ32 = σ42 = 4, σ52 = σ62 = 2.

23

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

M8 - 2 components scale mixture in Gaussian variables, with clear clustering

information in categorical variables (note, however, that according to Goodman (1974) the components are not identifiable from the categorical variables

alone in this situation, because there are not enough levels for only two variables; the Gaussian mixture makes the overall partition identifiable).

Component 1 n1 = 200 , µ1 = 0, σ12 = 1.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

Levels

1

2

3

0.9 0.1

0

0.8 0.1 0.1

Component 2 n2 = 300 , µ2 = 0, σ22 = 3.

Distributions of categorical variables:

Categorical

variable

Z1

Z2

1

0

0.1

Levels

2

3

0.1 0.9

0.1 0.8

From every model 50 datasets were generated (the small number is mainly due to

the computational complexity of fitting latent class clustering).

6.2

Clustering methods and quality measurement

Latent class clustering (LCC) as explained in Section 2 and clara as explained in

Section 5 based on Euclidean distances as defined in Section 4 were applied for

the number of clusters k between 2 and 9. The optimal number of clusters was

selected by the BIC for latent class clustering. For clara, two different methods to

determine the number of clusters were applied, namely CH and ASW, see Section

5. As opposed to ASW and CH, the BIC can theoretically estimate the number of

clusters to be 1; it was recorded during the simulations how often this would have

happened if 1 were included as a valid number of clusters. The results of this are

not shown because it hardly ever happened.

In order to run the whole simulation study involving different methods and statistics in R, the latent class model was fitted by an own R-implementation using

the R-package flexmix (Leisch 2004), which allows users to implement their own

drivers for mixture models not already covered by the package. The EM-algorthm

is run 10 times from random initial clusterings and the best solution is taken.

According to our experience, the resulting EM-algorithm behaves generally very

similar to the one in LatentGOLD, although the implemented refinements allow

LatentGOLD to find a little bit better solutions for some datasets.

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

24

clara was computed by the function clara in the R-package cluster. Default

settings were used for both packages.

Several criteria were used in order to assess the quality of the resulting clusterings.

The quality of recovery of the “true” partition was measured by the adjusted

Rand index (RAND; Hubert and Arabie, 1985). This compares two partitions of

the same set of objects (namely here the simulated partition as given in Section

6.1 and the partition yielded by the clustering method). A value of 1 indicates

identical partitions, 0 is the expected value if partitions are independent, which

means that negative values indicate bad agreement between the partitions.

However, recalling the remarks in Section 3, recovery of the true data generating

process is not seen as the main aim of clustering here (in reality such truth is

not available anyway, at least not in social stratification). Therefore, it was also

measured how well the methods achieved to bring similar observations together.

A difficulty here is that the criteria by which this can be measured coincide with

the criteria that can be used to estimate the number of components based on

dissimilarities, see Section 5. The three criteria ASW, CH and PH were applied to

all final clustering solutions. ASW and CH were also used to estimate the number

of clusters, and it is interesting to see how solutions that are not based on these

criteria compare with those where the respective criterion was optimised, whereas

PH was added as an external criterion.

It should be noted that the comparisons are, in several respects, not totally fair,

although one could argue that the sources for unfairness are somewhat balanced.

Data generation according to (2.1) gives latent class clustering some kind of advantage (particularly regarding RAND) in the simulations, because it makes sure that

its model assumptions are met, except of M7, where covariance matrices for the

continuous variables were not diagonal. On the other hand, obviously clara/CH is

favoured by the CH criterion, clara/ASW is favoured by the ASW criterion and

clara is generally by definition rather associated to the dissimilarity based criteria.

There is crucial problem with designing a “fairer” comparison for applications

in which “discovering the true underlying data generating mechanism” is not the

major aim (this is a problem for cluster validation criteria in general). If there were

a criterion that would optimally formalise what is required in a given application,

one could argue that the clustering method of choice should optimise this criterion

directly, which then would automatically mean that this criterion could not be

used for comparison. Therefore, the more “independent” of the clustering method

a criterion is, the less relevant it is expected to be.

Regarding the estimation of the number of clusters, the average estimated number

of clusters ANC and its standard deviation SNC were computed.

Furthermore, variable impact was evaluated in order to check to what extent clusterings were dominated by certain (continuous or nominal) variables. In order to

do this, the clustering methods were applied to all datasets with one variable at a

time left out, and the adjusted Rand index was computed between the resulting

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

25

partition and the one obtained on the full dataset. Values close to 1 here mean

that omitting a variable does not change the clustering much, and therefore that

the variable has a low impact on the clustering.

6.3

Results

The results of the simulation study are given in the Tables 1 and 2. Overall, they

are inconclusive. The quality of the methods depends strongly on the criterion by

which quality is measured, and to some extent on the simulation setup.

Typical standard deviations of simulated values were 0.03 for ASW, 30 for CH,

0.06 for PH, 0.09 for RAND (these varied about proportionally with√the average

and were usually lower for LCC/BIC); they have to be divided by 50 in order

to get (very roughly) estimated standard deviations for the averages, but a more

realistic idea of the precision of the comparisons could be obtained by paired tests.

For example, a paired t-test comparing the ASW values between clara/ASW and

clara/CH in M3 yields p = 0.002, comparing the two (quite close) CH-values

yields p = 0.003, comparing clara/ASW and clara/CH according to ASW (average

difference 0.004) in M2 is still significant at p = 0.009, whereas the ASW result

of LCC/BIC in the same model cannot be distinguished significantly from any of

the other two (both average differences 0.002, both p > 0.7).

As could be expected, clara/ASW was best according to ASW and LCC/BIC

according to RAND (often strongly so). clara/CH was best according to CH

in most situations, but LCC/BIC surprisingly outperformed it according to CH

in M2 (where it also achieved a very good ASW result) and M3. It levelled

clara/CH according to CH in M6 and did at least better than clara/ASW in M5.

In some other setups LCC/BIC performed much worse than the dissimilarity based

methods according to all three dissimilarity based criteria (particularly M7 and

M8).

In some setups (M2, M3, M4, M6), LCC/BIC was optimal according to PH. In

M4, this seems slightly odd, because LCC/BIC did much worse according to ASW

and CH. Overall, this means that LCC/BIC is not necessarily worse than the

dissimilarity based methods in grouping similar observations together, but this is

not reliable. Unfortunately it is difficult to see what the models M1, M7 and M8

(in which LCC/BIC did badly according to the dissimilarity based criteria) have

in common, and what separates them from M2, M3 and M6, in which LCC/BIC

did well. An explanation of some of the results is that the components in the

Gaussian variables in M7 and M8 cannot properly be interpreted as generating

similar within-component observations. M2, M3 and M6 are the models with

the strongest impact of the first (cluster separating) Gaussian variable on the

LCC/BIC clustering. Interestingly, this impact, and accordingly the dissimilarity

based quality of LCC/BIC, is lower in M1, in which mixture components are even

stronger separated by X1 than in M3, but in M1 the stronger information in the

categorical variables seems “distractive”.

26

6 A SIMULATION STUDY

M1

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M2

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M3

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M4

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M5

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M6

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M7

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

M8

Method

clara/ASW

clara/CH

LCC/BIC

ASW

0.236

0.213

0.179

CH

110

134

109

ASW

0.199

0.195

0.197

CH

129

135

150

ASW

0.187

0.179

0.162

CH

109

113

120

ASW

0.129

0.124

0.090

CH

72.7

79.0

60.2

ASW

0.395

0.314

0.281

CH

189

243

230

ASW

0.297

0.289

0.276

CH

269

288

288

ASW

0.303

0.294

0.229

CH

236

270

219

ASW

0.314

0.275

0.203

CH

124

142

101

Criterion

PH RAND

0.477

0.447

0.433

0.453

0.427