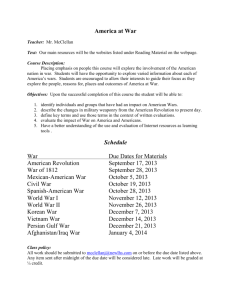

Document 12348042

advertisement