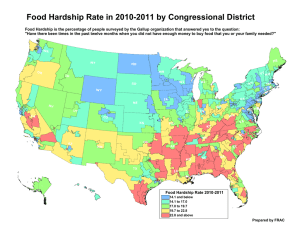

Mitigating Material Hardship:

advertisement