lUCN

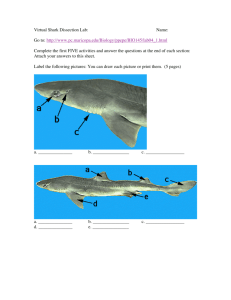

advertisement