The early childhood care and education workforce from 1990 through 2010: Changing dynamics and persistent concerns

advertisement

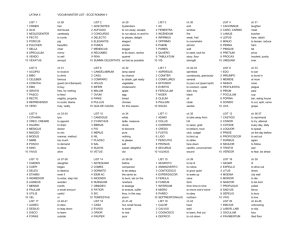

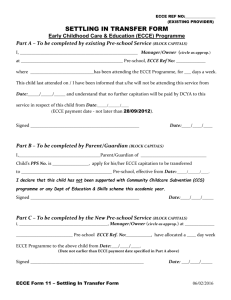

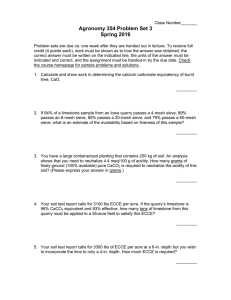

Theearlychildhoodcareandeducationworkforcefrom1990through2010: Changingdynamicsandpersistentconcerns DaphnaBassok,UniversityofVirginia,1 MariaFitzpatrick,CornellUniversity2 SusannaLoeb,StanfordUniversity3 AgustinaS.Paglayan,StanfordUniversity4 WearegratefultoDavidDeming,BruceFuller,DeborahStipek,andtwoanonymous refereesforusefulcommentsonpreviousdraftsofthispaper.Thisresearchwassupported byagrantfromtheInstituteofEducationSciences(R305A100574).Theviewsexpressed herearethoseoftheauthorsanddonotnecessarilyreflecttheviewsoftheUniversityof Virginia,CornellUniversity,StanfordUniversity,orIES.Anyremainingerrorsareourown. 1AssistantProfessor,CurrySchoolofEducation,UniversityofVirginia,405EmmetStreetSouth, Charlottesville,VA22904(dbassok@virginia.edu) 2AssistantProfessor,DepartmentofPolicyAnalysisandManagement,CornellUniversity,103MarthaVan RensselaerHall,Ithaca,NY14853(mdf98@cornell.edu) 3BarnettFamilyProfessor,StanfordUniversity,520GalvezMall,Stanford,CA94305(sloeb@stanford.edu) 4Doctoralstudent,StanfordUniversity,520GalvezMall,Stanford,CA94305(paglayan@stanford.edu) ABSTRACT Despiteheightenedpolicyinterestinearlychildhoodcareandeducation(ECCE),littleis knownabouttheECCEworkforcetodayortheextenttowhichthisworkforcehaschanged overaperiodofsubstantialinvestmentinthissector.Usingnationally‐representativedata, thispaperfillsthisgapbydocumentingchangesbetween1990‐2010intheeducational attainment,compensationandturnoveroftheECCEworkforce.Wefindthatthenational ECCEworkforceremainsalow‐education,low‐compensation,andhigh‐turnover workforce.Atthesametime,theaverageeducationalattainmentandcompensationof ECCEworkersincreasedsubstantiallyoverthepasttwodecadesandturnoverdecreased sharply.WedocumentamajorshiftinthecompositionoftheECCEworkforcetowards center‐basedsettingsandawayfromhome‐basedsettings.Surprisinglyhowever,thisshift towardsmoreregulatedsettingsisnottheprimarydriveroftheobservedchangesinthe ECCEworkforce.WeshowthatimprovementsinthecharacteristicsoftheECCEworkforce weredrivenprimarilybychangeswithinsectorsand,contrarytoourexpectations,we showthatthehome‐basedworkforce,whichfacestheleaststringentregulations, experiencedthemostimprovementovertheperiodexamined,thoughhome‐based workersremainsubstantiallydifferentfromformalcareworkers. INTRODUCTION IntheUnitedStates,mostchildrenunderagefivereceiveregularcarebysomeoneother thantheirparents(U.S.CensusBureau2010;Bassok2010).Earlychildhoodexperiences playacentralroleinshapingsubsequentdevelopmentaltrajectories,andtheimpactof theseearlyexperiencesdependslargelyonthequalityofcaregiversandteachers(Shonkoff andPhillips2000;Peisner‐Feinbergetal.2001;Knudsen,Heckman,CameronandShonkoff 2006;HamreandPianta2006;NationalScientificCouncilontheDevelopingChild2004, 2007). Growingrecognitionoftheimportanceofearlychildhoodcareandeducation (ECCE)ingeneral,andofECCEprovidersinparticular,hasheightenedpolicyinterestin strengtheningthequalityoftheECCEworkforce.In2011,thefederalgovernmentfunded theRacetotheTopEarlyLearningChallenge,acompetitivegrantprogramtosupport states’effortstoimproveearlychildhoodeducationprograms,andidentified“supportinga greatearlychildhoodeducationworkforce”asoneoffivekeyareasofreform.Thelatest reauthorizationofthefederalHeadStartprogramrequiresthatfiftypercentofHeadStart teachersholdaBachelor’sdegree(BA)inchilddevelopmentorarelatedfieldby2013 (Barnettetal.2010).Further,25statesareoperatingordevelopingQualityRatingand ImprovementSystems(QRIS)toassessandimprovethequalityofECCE,andmanyofthese QRISprogramsofferfinancialincentivestoprovidersthatinvestintheiremployees’ educationandtraining(Toutetal.2010). Despitetheinterestintheimprovementofthissector,weknowrelativelylittle aboutthecurrentstateoftheECCEworkforce,andevenlessabouttheextenttowhichthis workforcehaschangedovertime.ItiswelldocumentedthattheECCEworkforceis 1 characterizedbylowlevelsofeducation,wagesandstability(Brandon,2011;Howes, PhillipsandWhitebook1992;Cost,QualityandOutcomesStudyTeam1995;NICHDEarly ChildCareResearchNetwork2000;VandellandWolfe2000;CommitteeonEarly ChildhoodCareandEducationWorkforce;InstituteofMedicineandNationalResearch Council2012).Forinstance,theaverageannualincomeofpaidECCEworkersin2009 rangedfrom$11,500forthoseworkinginachild’shometo$18,000forpreschoolteachers (U.S.GovernmentAccountabilityOffice2012).5However,whilestudieshavedocumented theloweducation,wagesandstabilityofECCEworkersusingavarietyofdatasources,the diverseanddispersednatureoftheindustrymakessystematicanalysisdifficult.Arecent reportoftheNationalResearchCouncildescribeshowthelackofcomprehensivedata trackingthecharacteristicsoftheECCEworkforceseriouslylimitspolicymakers’effortsto facilitatechangeortrackimprovementsovertime(ADDCITATION). Overthepasttwentyyearsutilizationof“formal”ECCEservicessuchaspreschool andHeadStarthasincreasedrapidly.Thisincreasehasledtoadeclineintheshareof workersemployedinmore“informal”home‐basedsettings,suchasfamilychildcarehomes (Bassok,FitzpatrickandLoeb2012).Giventhatthehome‐basedsectorfacesmuchless stringentregulationsthantheformalsector,andisoftensingledoutforprovidingthe lowest‐qualitycare–theshifttowardsformalcaremayhavetranslatedintooverall improvementsintheECCEworkforceovertime.Unfortunately,attemptstodescribethe evolutionoftheECCEworkforcehavebeenlimitedduetothepaucityofdatathatallows 5Educationandturnoverstatisticspresentasimilarpicture.Forinstance,turnoverinCaliforniachildcare centersbetween1996and2000wasestimatedatabout75percent(Whitebooketal.2001)andanother studysurveyingchildcarecentersinIowa,Kansas,NebraskaandMissouri,foundthat40percentof caregiversintendedtoleavetheECCEindustrywithinlessthanfiveyears(Torquati,RaikesandHuddleston‐ Casas2007). 2 forreliablecomparisonsoftheworkforceovertime(Saluja,EarlyandClifford2002; BrandonandMartinez‐Beck2006;Kagan,KauerzandTarrant2008). ThefewstudiesthathaveexaminedtheevolutionoftheECCEworkforceovertime actuallysuggestthatthequalificationsoftheworkforcehaveeitherchangedonlymodestly orhavedeclined(Whitebooketal.2001;Saluja,EarlyandClifford2002;Herzenberg,Price andBradley2005;BellmandWhitebook2006).However,thesestudiesdonotemploy nationallyrepresentativedataand/orfocusonlyonasinglesectoroftheECCEindustry, typicallychildcarecenters.Thelackofknowledgeaboutchangeswithinthehome‐based workforcerepresentsaparticularlyrelevantgapintheliterature,giventhatthissector accountsforaboutathirdofthenationalECCEworkforce(U.S.GovernmentAccountability Office2012). Inthispolicybriefwemakeuseofnationally‐representativedatathatencompass workersinallthreeECCEsectors–centers,homesandschools–toaddressthreequestions: (1)WhatarethecharacteristicsoftheECCEworkforceasof2010? (2)Howdidthecharacteristicsofthisworkforcechangebetween1990and2010? (3)Towhatextentaretheoverallchangesdrivenbyachangeintherelativeimportanceof eachsector(centers,homes,schools),andtowhatextentaretheyexplainedbychangesin thecharacteristicsoftheworkforceswithineachsector? WefocusonfouroutcomestogaugethewellbeingoftheECCEworkforceand plausiblyproxyforECCEquality:(1)theeducationalattainmentofworkers;(2)their compensation;(3)theextenttowhichworkersexittheindustryoverayear;and(4)the occupationalprestigeofthosewhoentertheECCEworkforceeachyearfromother occupations.Improvementsalongthesedimensionsarelikelytoreflectanincreasedability 3 toattractandretainqualifiedworkersintotheECCEindustry,andinturnmayimply higherqualityexperiencesforyoungchildren.6 Wefindthatthe“low‐education,low‐compensation,high‐turnover”characterization ofthenationalECCEworkforcecontinuestobevalid.Atthesametime,weshowthatthe averageeducationalattainmentandcompensationoftheECCEworkforceincreased between1990and2010,andthatturnoverfromtheECCEindustrydecreased substantially.Ourresultsdifferfromearlierstudiesthathighlightnegativeorstagnant trendsintheECCEworkforce.Thesedifferencesarelikelyexplainedbyourfocusona morerecentperiodofanalysisandouruseofnationaldataincludingworkersfromall threechildcaresectors.Wealsoshowthatchangesinthecharacteristicsofthenational workforcearemostlyexplainedbychangesinthecharacteristicsofworkerswithineach sectorandlesssobytheshifttowardcenter‐andschool‐basedsettings.Surprisingly,we findthatchangesalongalldimensionsanalyzedweremostpronouncedamonghome‐ basedworkers. DATA WeanalyzedatafromtheMarchSupplementoftheCurrentPopulationSurvey(CPS),a nationallyrepresentativehouseholdsurveythatisadministeredeverymonthbytheU.S. 6Whileideallywecouldalsoassesschangesovertimeindirectmeasuresofcaregiverquality,nationaldata trackingsuchmeasuresovertimearenotavailable.Severalstudieshavesoughttodeterminewhetherthere isacausalrelationshipbetweenourproxiesandthequalityofcarechildrenexperience.Theevidencehereis mixed.Asdescribedabove,improvementsinteachers’educationalattainmentareoftenpursuedasastrategy toimprovequality,andsomestudiessuggestthat,oversomerange,higherlevelsofeducationarerelatedto betterclassroompractices(Blau2000).Ontheotherhand,Early(2007)raisesdoubtsabouttherelationship betweenspecificdegreesandchildoutcomes.Higherwagesareassociatedwithbetterclassroompractices andlowerturnoverfromECCEjobs(Blau2000;WhitebookandSakai2003).Whilewearenotawareof studiesinvestigatingtheimpactofindustryturnoveronchildren’sdevelopment,thefewstudiesontherole ofjobturnovershowthatchildrenwhospendmoretimewiththeircaregiver,andthosewhodonot experienceachangeintheprimarycaregiveroverthecourseofayear,establishmorenurturing relationshipswiththeircaregiverandexhibitbettercognitiveoutcomes(Elicker,Fortner‐WoodandNoppe 1999;TranandWinsler2011). 4 CensusandtheBureauofLaborStatistics.UsingtheCensus1990and2002Industryand OccupationalCodes,weidentifyECCEworkersanddisaggregatethisbroadgroupinto center‐,home‐,andschool‐basedworkers.Wepurposefullyimplementabroadand inclusivedefinitionoftheindustry.Specifically,ourcenter‐basedcategoryincludesall workerswho(1)arenotself‐employed;(2)workineitherthe“childdaycareservices” industry,orhavechildcareoccupations(e.g.,“childcareworkers”,“pre‐kindergartenor kindergartenteachers”,“earlychildhoodteacher’sassistants”);and(3)workinan industryotherthan“elementaryandsecondaryschools”,“privatehouseholds”,“individual andfamilyservices”,or“familychildcarehomes”.7Ourdefinitionofthehome‐basedECCE workforceincludes(1)allself‐employedindividualswhoreportthattheyworkinthe “childdaycareservices”industry;(2)allthoseemployedinthe“familychildcarehomes” industry;(3)thosewhohavechildcareoccupations(e.g.,“childcareworkers”,“private householdchildcareworkers”,“pre‐kindergartenorkindergartenteachers”,“early childhoodteacher’sassistants”)andareemployedinthe“privatehouseholds”or “individualandfamilyservices”industries;and(4)thosewhohavechildcareoccupations andareself‐employedinotherindustriesexceptfor“elementaryandsecondaryschools”.8 Finally,wedefinetheschool‐basedECCEworkforceas“pre‐kindergartenandkindergarten teachers”and“earlychildhoodteacherassistants”employedinthe“elementaryand secondaryschools”industry.WeobservewhethereachrespondentwasanECCEworkerin 7Onaverageovertheperiod1990‐2010,82.8percentofindividualsidentifiedascenter‐basedECCEworkers wereemployedinthe“childdaycareservices”industry;theremaining17.2percentwereinotherindustries. 8 Our“home‐basedworkforce”includesallindividualswhotakecareofarelative,friend,orneighbor’schild, whoreportthistobetheirjob.TheCPSreliesonself‐reportsandsomerelatives,friendsandneighborswho assumechildcareresponsibilitiesmaynotreportthisasajobandwillthereforebeexcludedfromour analysis.Totheextentthatthosewhofailtoreporttheiremploymentmaydifferinimportantwayfromthose whodoidentifythisway,ourcharacterizationmaysufferfrombias. 5 theweekofreferenceandwhethertheirlongestjobinthepreviouscalendaryearwasan ECCEjob. Theworkforcecharacteristicsthatweanalyzearemeasuredasfollows: Educationalattainment:TheCPScollectsinformationabouteachhouseholdmember’s highestlevelofeducationasoftheweekofreference.Inkeepingwithpriorstudies,we describechangesintheshareofECCEworkerswithlessthanahighschooldegree,exactly ahighschooldegree,atleastsomecollegeeducationbutnoBA,andatleastaBA.9 Compensation:Weobserveeachindividual’sannualearningsfromthelongestjobheldin thepreviouscalendaryear.Wedescribethemeanannualearningsofthosewhosemainjob inthepreviouscalendaryearwasanECCEjob.Wealsoestimatethehourlyearningsof theseworkers,buthererestrictouranalysistothosewhowerefull‐yearworkersinthe previouscalendaryear.10Weexpressbothearningsvariablesin2010dollars. Individualsalsoreportwhetheranyemployerhelpedpayforapensionand/or healthplaninthepreviouscalendaryear.Weusethisinformationtoconstructtheshareof ECCEworkersthatreceivedthisnon‐salaryformofcompensation.Herewerestrictour sampletoworkerswhosemainjobinthepreviouscalendaryearwasanECCEjob,and,in 9Informationoneducationalattainmentisavailablefrom1992to2010.Mostotherworkforcecharacteristics areavailablefor1990to2010.Theexceptionisinformationonearningsandbenefitsavailable from1990to2009. 10WemakethisrestrictionbecausetheCPScollectsinformationabouthourlywagesonlyforasubsampleof the March interviewees which excludes all self‐employed individuals, thus excluding a large proportion of home‐basedworkers.Ratherthanexcludinghome‐basedworkersinouranalysis,weestimatedhourlywages ofECCEworkersbasedontheirannualearningsandtheirreportedhoursworkedinatypicalweek.Because the CPS does not specify the number of weeks worked in the past year, we limited analysis to full‐year workersforwhomweassumed50weeksofwork(seetechnicalappendixformoredetails).Notethatour estimatesthereforeapplyonlytothoseECCEworkerswhowereemployedonafull‐yearbasis(i.e.thosewho worked 9 months or more). These represent 46 and 65 percent of those workers who in 1990 and 2010, respectively,reportedthattheirmainjobinthepreviousyearhadbeenanECCEjob.Thesubsetoffull‐year ECCE workers appears to be slightly more educated than the aggregate ECCE workforce, although the differencesbetweenthetwogroupsarenotstatisticallysignificant.Still,ourestimationmayoverestimatethe hourlyearningsoftheaggregateworkforce. 6 ordertobesurethebenefitswerereceivedfromanECCEemployer,includeonlythose workerswhoreportedtheyhadonlyoneemployerinthepreviouscalendaryear.11 Year‐to‐yearindustryturnover:Tomeasurechildcareindustryturnoverrates,we exploitthefactthattheCPSprovidesinformationaboutanindividual’sindustryand occupationbothintheweekofreferenceandforthelongestjobheldintheprevious calendaryear.Amongindividualswhosemainjobinthepreviouscalendaryearwasan ECCEjob,weestimatetheindustryturnoverrateastheshareofthosewhowerenolonger intheECCEworkforceduringtheweekofreference.Ananalogousmethodisusedby HarrisandAdams(2007)tomeasureturnoverfromelementaryandsecondaryteaching. WecancalculateindustryturnoverwiththeCPSfrom1990to2010.Ourmeasureonly captureswhetherindividualsremainedintheECCEworkforce;amongthosethatremain, wecannotdistinguishwhetherindividualschangedjobs.Thus,year‐to‐yearindustry turnoverisalowerboundestimateofthelevelofinstabilityexperiencedbychildren. OccupationalprestigeofentrantsintotheECCEworkforce:Wecombinethe informationonaworker’soccupationprovidedbytheCPSwiththewidelyused methodologydevelopedbyCharlesNamandcolleagues(Nam2000;NamandBoyd2004), tocreateavariablethatassignseachnewentranttotheECCEworkforceascorebasedon theoccupationalprestigeoftheirpreviousjob.Aparticularoccupation’sprestigescoreis constructedbycomparingthemedianearningsandeducationalattainmentofworkersin thatoccupationvis‐à‐vistheearningsandeducationofworkersinallotheroccupations.An 11AmongallworkerswhosemainjobinthepreviouscalendaryearwasanECCEjob,theproportionwhohad onlyoneemployerincreasedfrom75percentin1990to84percentin2010.Throughoutthewholeperiod, these workers earn about 5% more than those whose main job in the previous calendar year was also an ECCE job but who had more than one employer. Thus our analysis may overestimate the share of workers withnon‐salarybenefitsintheaggregateECCEworkforce. 7 occupation’sscorecanrangefrom0to100,andreflectsthepercentageofindividualsinthe laborforcewhoareinoccupationswithcombinedlevelsofeducationandearningsbelow thatoccupation.Weusethesescorestoexaminetheaverageoccupationalstatusof individualswhosemainjobinthecalendaryearbeforethesurveywasoutsidetheECCE industry,butwhowereECCEworkersintheweekofreference.Increasesinthis occupationalmeasureovertimeimplythatthosewhoareenteringtheECCEworkforceare comingfrombettereducatedandbetterpaidoccupationsthanthosewhowereentering theworkforceinpreviousyears. Asresearchershavelongpointedout,existingdatasetsfailtofullyandaccurately capturethecomplexityoftheECCEworkforceovertime(CommitteeonEarlyChildhood CareandEducationWorkforce;InstituteofMedicineandNationalResearchCouncil2012; Bellm&Whitebook,2006;PhillipsandWhitebook,1986).AlthoughtheCPSiswell‐suited fornationallyrepresentativeanalysistrackingtrendsovertime,ithasanumberofkey limitations:(1)itreliesonself‐reporteddataonemployment,andthereforelikelyexcludes manyunpaidECCEworkersandsomepaidfamily,friendsandneighborswhotakecareof childrenbutdonotreportchildcareastheiroccupation;(2)itdoesnotenableusto distinguishbetweenpreschoolandkindergartenteachers,ormoregenerally,todistinguish ECCEworkersbytheageofthechildrentheyserve;and(3)itdoesnotcollectdetaileddata thatarerelevanttocharacterizeECCEworkers,suchasthelevelofECCE‐specifictraining, theresponsibilitiestheyhave,orthequalityoftheirinteractionwithchildren.Wereturn totheselimitationsindiscussingthegeneralizabilityofourresults. METHODS 8 Toaddressourfirstandsecondresearchquestions,wepresentthevariablesofinterestin 2010,anddiscusstheirchangeovertheperiod1990‐2010.Weassesswhethertrendsin theECCEworkforcedifferfrombroadertrendsintheeconomybycomparingchangesin thatworkforcetochangesamongtwocomparisongroups:allfemaleworkersandlow‐ wageworkers.12Toaddressthethirdresearchquestion,twosetsofsimulationsallowusto disentangletheextenttowhichtheoverallchangesintheECCEworkforceareexplainedby anincreaseintherelativesizeofthemoreregulatedECCEsectorsorbychangesinthe workforcewithineachsector.13GiventherelativelysmallsamplesizeoftheCPSineach year,forallanalysesweusethree‐yearmovingaveragestoincreasetheprecisionofour estimates. RESULTS TheECCEworkforceasof2010 Wefindthatthe“low‐education,low‐compensation,high‐turnover”labelcontinuestobea validcharacterizationofthe2.2millionECCEworkersrepresentedinoursample.As showninTable1Table1,in2010,nearly40percentoftheECCEworkforcehadatmosta Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Check spelling and grammar 12 FemaleworkersarearelevantcomparisongroupasfemalescomprisethevastmajorityofECCEworkers. Basedonourcalculations,over95percentofECCEworkersovertheperiodofanalysiswerewomen.The low‐wageworkercomparisonincludesworkersfromthemainindustriesfromwhichECCEworkerscome whentheyenterthechildcareindustry,aswellastowhichECCEworkersmigratewhentheyleavetheECCE workforce.Weconsiderthefollowingindustries:beautysalons,foodservices,entertainmentandrecreation services,grocerystores,departmentstores,andnon‐teachingjobsinelementaryandsecondaryschools(e.g., busdrivers,cooks,janitors,teacheraides,secretariesandadministrativeassistants).Together,overthefull periodofthestudy,theseindustriesrepresentaboutathirdofmigrationfromanotherindustryintochild care,andfromchildcaretoanotherindustry. 13 First,weestimatewhattheoverallchangeintheECCEworkforce’scharacteristicswouldhavebeenhadthe distributionoftheworkforceacrossthethreesectors(center,homesandschools)changedasitdid,but assumingthatthecharacteristicsofworkerswithineachsectorremainedthesameasin1990.Then,to estimatethepartoftheoverallchangethatisdrivenbychangesinthecharacteristicsofworkerswithineach sector,weestimatewhattheoverallchangeintheworkforce’scharacteristicswouldhavebeenhadthe characteristicsoftheworkerswithineachofthesectorschangedastheydid,butassumingthedistributionof theworkforceacrossthesectorsremainedthesameasin1990.Theequationsusedforthesesimulationsare providedintheTechnicalAppendix. 9 highschooldegreeandathirdoftheworkforcehadsomecollegebutnoBachelor’sdegree. In2009,theaverageECCEworkerearnedanannualincomeof$16,215andanhourlywage of$11.7,andonly28percentofECCEworkersreceivedapensionand/orhealthbenefits fromtheiremployer.14Worryingly,aboutafourthofthoseworkerswhohadbeen employedintheECCEindustryin2009werenolongerthatindustryby2010.Further,our analysisoftheoccupationalprestigeofentrantssuggeststhatECCEwasarelatively unattractiveindustrytoenterin2010,attractingindividualsfromoccupationsthaton averagehadlowerlevelsofeducationandearningsthanthreefifthsofthecountry’slabor force. ThedisaggregatedresultsshowninTable2highlightstarkdifferencesacross sectors.In2010,about56percentofECCEworkerswereemployedincenter‐based settings;26percent,inhome‐basedsettings;and18percent,inschools.Consistentwith evidencefrompriorstudies,wefindthattheschool‐basedworkforceexhibitsthehighest levelsofformaleducation,compensation,andstability,whilethehome‐basedworkforce exhibitsthelowest.Thecenter‐basedworkforcefallsinthemiddle,butismoresimilarto thehome‐basedthantotheschool‐basedworkforce.Forinstance,17.1percentofschool‐ basedworkershaveatmostahigh‐schooldegree.Thisproportionascendsto39.8percent and50.7percentamongcenter‐andhome‐basedworkers,respectively.Similarly,while school‐basedworkersearnanaverageannualincomeof$27,014,centerworkersearnon averagejustoverhalfthisamount($14,567)andtheannualearningsofhome‐based workersareevenlower($12,415).Finally,while13.6percentofthosewhowereschool‐ 14 Recall also that these figures likely overestimate the true compensation of the full ECCE workforce, due to our sampling restrictions (e.g. hourly wages are calculated based on full‐year workers, benefits are calculated based on workers with only one job in the past year). 10 basedECCEworkersin2009hadlefttheECCEindustryby2010,theindustryturnoverrate amongcenter‐andhome‐basedworkersin2010was24.4and28.5percent,respectively. ChangesinthecharacteristicsoftheECCEworkforcein1990‐2010 Theverylowlevelsofformaleducation,compensationandstabilityamongtheECCE workforcewarrantconcern.However,asTable1indicates,wealsofindmeaningfulsignsof improvement.Infact,amongtheECCEworkforceasawholeweshowthatallofthe characteristicsanalyzed–education,compensation,turnoverandprestigeofentrants– exhibitedsignificantandsubstantialchangesinthedirectionhypothesizedtoimprove ECCEquality.15 AsshowninFigure1Figure1,theshareofECCEworkerswithatleastsomecollege educationrosefrom47to62percentbetween1992and2010.Meanannualearnings increasedby51percent,from$10,746to$16,215between1990and2009.Whilepartof thisincreasewasdrivenbyanincreaseinthenumberofhoursworkedbyECCEworkers,16 themeanhourlyearningsofECCEworkersalsoincreasedsubstantiallyoverthatperiod (by33percent,from$8.8to$11.7perhour),andsodidtheshareofECCEworkerswith employer‐paidpensionand/orhealthbenefits(from19to28percent).Annualturnover fromtheECCEindustrydecreasedsubstantiallyovertheperiodofanalysis(from32.9 percentin1990to23.6percentin2010).Finally,individualswhomovedintochildcare fromotheroccupationsin2010camefromsomewhatmoreprestigiousoccupationsthan thosewhomovedintochildcarein1990.TheaverageoccupationalprestigescoreofECCE 15Thechangesineducationalattainment,compensationandindustryturnoverthatwediscussthroughout arestatisticallysignificantlydifferentfromzeroatthe5percentlevel.Changesintheoccupationalprestige scoreofECCEentrantsaresignificantlydifferentfromzeroatthe15percentlevel.Notethattheanalysisof averageoccupationalprestigescoresappliesonlytoindividualswhoenteredtheECCEworkforceinagiven year.Thisisaverysmallsample,soweevaluatesignificanceatthe5,10and15percentlevels. 16Themeanhoursworkedperweekincreasedfrom29.9to31.8between1990and2010. 11 Formatted: Font: Not Bold entrantsincreasedby4.7percentilepointsoverthisperiod,from37.6to42.3,perhaps indicatinganimprovementintheECCEindustry’sabilitytoattractmorequalifiedworkers. ThechangesobservedamongtheECCEworkforcedonotsimplyreflecttrendsinthe femalelaborforceand/orinlow‐wageindustries.Comparedtofemaleworkers,theECCE workforceexhibitedalargerincreaseincompensationandasteeperdeclineinindustry turnover;andcomparedtolow‐wageworkers,allvariablesexhibitedalarger improvementamongECCEworkers.Further,thechangesobservedreflectastabletrend withintheindustryandarenottheproductoftheeconomiccrisisthatbeganin2008.17 Sector‐specificchanges? InTable2weshowthattheoverallimprovementsseeninthisworkforcearedrivenby improvementsamonghome‐basedworkers,andtoalesserextentcenter‐basedworkers. Inthehome‐basedsector,theaverageeducationalattainment,compensationandindustry turnoverofworkersimprovedsignificantlyandsubstantiallyovertheperiodofanalysis. Withrespecttoeducationalattainment,therewasasignificantincreaseintheshareof workerswithatleastsomecollege(by21.4percentagepoints(p.p.)),andasignificant decreaseintheshareofworkerswithlessthanahighschooldegree(by17.8p.p.).The averageannualandhourlyearningsofhome‐basedworkersincreasedby92and50 percent,respectively,andtheshareofhome‐basedworkerswithpensionorhealthbenefits roseaswell(by4.5p.p.).Finally,industryturnoverdeclinedamonghome‐basedworkers (by8.4p.p.,from36.9percentin1990to28.5in2010). 17OneplausiblehypothesisisthattheobservedimprovementsinECCEworkers’qualificationsandstability aretheproductoftheeconomiccrisis.However,insupplementaryanalysisavailableuponrequest,we exploredwhethertherewerechangesintrendsfollowingtheeconomiccrisisthatbeganin2008.Wefindno evidencetosupportthisclaimand,ifanything,ourresultssuggestthattheimprovementinECCEworkers’ characteristicswasstalledorreversedduringthecrisisperiod. 12 Changeswithinthecenter‐basedsectoralsosuggestimprovementsovertime,but thesechangesareofasmallermagnitude.Forinstance,between1990and2009,the averageannualearningsamongcenter‐basedECCEworkersincreasedby35percentand averagehourlyearningsroseby18percent.Industryturnoverratedroppedsignificantly, from34percentin1990to24.4percentin2010.Othercharacteristicsappeartochangein adirectionconsistentwithimprovement,althoughthechangesarenotstatistically significant.Differencesremainbetweenthesectorswithrespecttoallthecharacteristics analyzed,butthepronouncedchangeswithinthehome‐basedsectorimplyanarrowingof thegapwithrespecttotheothertwosectors. Expansionofformalcareasanexplanationforgains? AsshowninthefourthpanelofFigure1,between1990and2010therewasasignificant changeintherelativeimportantoftheECCEsectorsinaccountingforthesizeofthe aggregateworkforce.Therelativeimportanceofhome‐basedworkersdeclinedsharply(by 21.8p.p.),compensatedmostlybyanincreaseintherelativeimportanceofcenter‐based workers(by17.5p.p.).Althoughtherelativeimportanceofschool‐basedworkers increasedonlyslightly(by4.3p.p.),thenumberofworkersinthissectorincreasedby45 percentoverthistimeperiod,atrendconsistentwithboththeexpansionofstatepre‐ kindergartenprogramsandtheshifttowardsfull‐daykindergartens.Thenumberof center‐basedworkersalsoincreaseddramatically(by61percent),whilethenumberof home‐basedworkersdecreased(by39percent).ThisredistributionofECCEworkersfrom childcarehomestocentersandschoolsisconsistentwiththerecentdeclineintheshareof childrenunderagefivewhosemainchildcarearrangementisinahomesetting(U.S. CensusBureau2010). 13 Asdiscussedabove,home‐basedworkershavefarlowerlevelsofeducationand compensationandhigherlevelsofindustryturnoverthandocenter‐orschool‐based workers.Thedeclineintherelativeimportanceofhome‐basedworkersisoneplausible explanationfortheobservedincreaseintheeducationalattainment,compensationand stabilityofthenationalECCEworkforce.However,changesinthesecharacteristicswithin sectorsarealsorelevant–and,infact,morerelevantthanthechangesinthedistribution theworkforceacrosssectors. WedecomposeaggregatechangesintheECCEworkforceintothepartexplainedby theexpansionoftheformalsectorandthepartexplainedbychangesinthecharacteristics ofworkerswithinthesectors.WepresenttheestimationsinPanelAofTable3.Whileboth factorscontributetotheoverallchange,formostvariables(educationalattainment,annual andhourlywages,andindustryturnover),changeswithinthesectorsexplainmostofthe aggregateimprovement,withchangesintherelativeimportanceofthesectorsexplaining onlyasmallportionoftheoverallimprovement.Forexample,increasesinearningswithin sectorsexplain78percentoftheoverallincreaseinannualearnings,whilethe redistributionofworkersacrosssectorsexplainsonly22percent.Similarly,within‐sector changesexplain86percentofthedeclineinindustryturnover. Further,asreportedinPanelBofTable3,changeswithinthehome‐based workforceexplainmostofthechangeineducationalattainmentandearningsthatis attributabletowithin‐sectorchanges.Indeed,improvementswithinthehome‐basedsector driveovertwothirdsoftheincreasesintheECCEworkforce’seducationalattainment. DISCUSSION 14 ThispolicybriefhighlightsthecurrentstateoftheECCEworkforceandexploreswhether thisworkforcehasexperiencedmeaningfulchangesoveraperiodcharacterizedby heightenedinterestandinvestmentinearlychildhoodprograms.Echoingearlierwork,we findthatthislaborforcecontinuestobecharacterizedbyverylowlevelsofeducation, compensationandstability.However,wealsoshowthatboththeeducationalattainment andthecompensationoftheECCEworkforceincreasedmeaningfullybetween1990and 2010andthatturnoverfromtheECCEindustrydecreasedsubstantially.Takentogether thefindingsaremixed,highlightingbothimprovementsovertimeandthepersistenceof troublingissues.Forexample,ourdatashowthatin1992ECCEworkerswithaBAearned 47percentlessthanelementaryschoolteacherswiththesameeducationallevel.Despite thesignificantincreasesinbotheducationalattainmentandearningsamongECCEworkers thatwedocumentinthispaper,in2009ECCEworkersstillearned38percentlessthan elementaryschoolteachers.Givenourincreasedunderstandingoftheimportanceofearly childhoodinterventionsandofhigh‐qualityECCEproviders,thesepatternsareconcerning. However,thepositivetrendswedocumentsuggestthatsubstantialchangesinthis workforceareinfacttakingplace. Itisworthnotingthatthepositivetrendswedocumentdiffersignificantlyfrom thosereportedinpriorstudies,whichdocumentadeclineormodestchangeinthe educationalattainmentandcompensationoftheECCEworkforce.Oneexplanationisthat priorstudieshavegenerallyfocusedonthecenter‐basedworkforceandhavenot accountedfortheevolutionofthehome‐basedworkforce,wherewefindmeaningful improvements(Whitebooketal.2001;Saluja,EarlyandClifford2002;Herzenberg,Price andBradley2005;BellmandWhitebook2006). 15 Asecondexplanationisthatourstudymakesuseofmorecurrentdatathanearlier work.Forinstance,anearlierstudythatreliesonthesamedatausedherebuttracksthe center‐basedworkforceonlythrough2003reportsadeclineintheproportionofthat workforcethatholdsaBA(Herzenberg,PriceandBradley2005).Wereplicatethatfinding here,butshowthatbetween2004and2010thistrendisreversed.Overallwedonot observesignificantchanges(eitherincreasesordecreases)intheeducationalattainmentof thecenter‐basedworkforceovertheperiod1990‐2010,butdocumentsignificant improvementsinthecompensationandstabilityofthisworkforce. WealsodocumentadramaticreconfigurationoftheECCEworkforce,suchthatthe majorityofworkersnowworkinformalratherthanhome‐basedsettings.Surprisingly, however,weshowthattheshiftawayfromhome‐basedcareandtowardscenter‐based settingsisnottheprimaryexplanationfortheimprovementsobservedintheindustryat large.Infact,mostoftheimprovementsintheECCEworkforceareexplainedbywithin‐ sectorimprovementsinthecharacteristicsofworkers.Further,whilethecenter‐based workforceexhibitedsignificantincreasesinearningsandaremarkabledeclineinindustry turnover,improvementswithinthehome‐basedworkforceweretheprimarydriverofthe increaseintheeducationalattainmentandearningsoftheaggregateECCEworkforce. Thesefindings–thattheoverallimprovementoftheECCEworkforcewasprimarily drivenbyimprovementswithinthehome‐basedworkforce–aresurprisinginlightofthe policyemphasisonexpandingandimprovingformalizedECCEsettingssuchaspreschools andpre‐kindergartenprogramsoverinformalsettings.Improvementswithinthehome‐ basedworkforcemaybetheresultofrecenteffortstoincreasethequalificationsand stabilityoftheseworkers.Forinstance,recentinitiativesrewardparticipationin 16 professionaldevelopmentandtheacquisitionoffurthereducation;supplementthewages ofhome‐basedworkerstoensuretheymeetalocally‐determinedminimumlivingwage, andfacilitatetheprovisionofemployer‐sponsoredhealthplansbypoolingtogether workersfromdifferentchildcarecentersandhomes(Kagan,KauerzandTarrant2008). Still,furtherstudyisneededtounderstandwhathasdriventheobservedimprovementin theeducation,compensationandstabilityofhome‐basedworkers,tounderstandhowto continuethispositiveandunexpectedtrend. Studylimitations WhilethecurrentstudyprovidesnewevidenceaboutthecurrentstatusoftheECCE workforceanditschangingnatureoverthepasttwodecades,theCPSwasnotdesignedto studytheECCEindustryandseveralofitslimitationsareworthhighlighting: First,theCPS,whilecommonlyusedinanalysesofworkers,reliesonself‐reported data.TotheextentthatcertainsegmentsoftheECCEworkforcearelesslikelytoreport theiremployment,ourestimateswillnotaccuratelygeneralizetotheECCEworkforceinits entirety.Further,ifthesenon‐reportershavelowerearningsandeducationalattainment thandootherworkers,ourfindingswilloverestimateconditionsinthisindustry,a troublingpointgiventhealreadylowlevelswedocument.Whileweareunabletoassess theextentofnon‐reportinginoursample,itislikelyweexcludesomeportionofthe informalsectorincludingunpaidworkers,paidworkerswhodonotreporttaxes,orpaid family,friendsandneighborswhodespiteassumingchildcareresponsibilitiesdonot reportitasajob.Theseinformalsettingsrepresentameaningfulportionofthemarket,and morenuanceddataarenecessarytobetterunderstandthecompositionofthisgroup. 17 Second,theCPSdoesnotprovidedirectmeasuresofcarequalityandthuscannotbe usedtoassesswhetherandhowmoreproximalmeasuresofcarequalityhavechanged. WhileouroutcomesprovideaclearpictureoftheeconomicstatusoftheECCEworkforce, animportantissueinitsownright,ultimatelypolicymakerswishtoimproveearly childhoodexperiencesforchildrenandtherelationshipbetweeneachofthesemeasures andcarequalityisnotaswellunderstoodaswewouldlike.Itisdifficulttoknow,for example,towhatextentchangesinearningsovertimeamounttobettercareforyoung children.Wehaveinterpretedourfindingsasindicativeofimprovementsinthequalityof theECCEworkforce,butacompetinghypothesisisthattheincreaseinECCEworkers’ compensationandthereductionofturnoverreflectanincreaseinthedemandforECCE services,withoutacorrespondingimprovementintheactualqualityoftheseworkers. Additionalworkinvestigatingthelinkbetweenstructuralmeasuressuchastheones availableinadministrativedatasetswouldhelphere. Third,ourstatisticalinferencesarelimitedbyoursmallsamplesize.EachMarch, theCPSsurveysaround670center‐basedworkers,530home‐basedworkersand230 school‐basedECCEworkers.Usingthree‐yearmovingaverages,wewereabletodescribe theevolutionofthecenter‐andhome‐basedworkforceswithreasonableprecision. However,oursamplesizewastoosmalltomakereliableinferencesabouttheevolutionof theschool‐basedworkforce. Finally,theCPScannotbeusedtodistinguishbetweenECCEworkerswhowork withinfantsandtoddlers,andthosewhoworkwithpreschoolers.Similarlyweareunable todistinguishbetweenpre‐kindergartenandkindergartenemployees.Datathatallowsfor 18 thesetypesofdelineationswouldbetterallowustounpacktrendsandbegintounderstand themechanismsdrivingthesepatterns. Conclusion Whileourfindingsechootherrecentworkonthelowlevelsofearningsandeducation withintheECCEworkforce,ourfindingsalsoshedanoptimisticlightonthepossibilityof positiveimprovements.Weshowthatthequalifications,compensationandstabilityofthe ECCEworkforcecanimprove,andinfacthaveimprovedmeaningfullyoverthepasttwo decades.ThedeclineinturnoverfromtheECCEindustryhasbeenparticularlymarked. Whilesomedegreeofturnovermaybedesirableinordertoreplaceineffectiveworkers, theannualECCEindustryturnoverratein1990was32.9percent,roughlythreetimes higherthantheindustryturnoverrateof11percentobservedamongelementaryand secondaryeducationteachers.By2010,however,thegapbetweenthetwohadnarrowed significantly,owingtothereductioninturnoveramongECCEworkers.Toourknowledge, oursisthefirststudytolookattheevolutionofturnoverforanationallyrepresentative sampleoftheECCEworkforce.Whileweareunabletoobservejobturnover,whichisa moreproximalmeasureoftheinstabilitychildrenexperience,industryturnoverisan importantmeasureinitsownright,showingthatindividualsarestayingwithinthe industrylongerthantheydidinthepastwhichmaytranslatetopositiveoutcomesfor childrenandmayindicatethatearlychildhoodjobsaremoreattractivethantheyonce were. TheimprovementswehaveidentifiedforECCEworkershavetakenplacewithin boththecenter‐andhome‐basedsectors,whichtogetheraccountforovereightypercentof theworkforce.Improvementswithinhome‐basedchildcarehavebeenparticularly 19 remarkable.Totheextentthatthecharacteristicsweanalyzedare,infact,proxiesofECCE quality,ourfindingsimplyanarrowinginthequalitygapbetweenhome‐basedandother moreformalizedtypesofchildcare.Thisfindingisimportantbecauseasrecentlyas2005, thehome‐basedsector,historicallysingledoutasthelowest‐qualitysectorwithinchild care,servedaroundfortypercentofchildrenunderfiveyearswhosemotherswere employed(U.S.CensusBureau2010),andthereissomeevidencethatitisthepreferred typeofarrangementamongHispanicfamilies(Fuller,HollowayandLiang1996;Liang, FullerandSinger2000;Fuller2008).Putdifferently,workersinchildcarehomesremain substantiallylessqualifiedthanworkersintheformalchildcaresector,butthetrendswe observesuggestthatclosingthequalitygapbetweenthesectorsispossible. 20 Figure1.EvolutionofselectedcharacteristicsoftheECCEworkforce,andoftherelativeimportanceofeachECCEsector,over time(1990‐2010) Share of ECCE workers with at least some college education, by sector, 1990‐2009 (as a % of ECCE workers in each sector) Mean hourly earnings of full‐year ECCE workers, by sector, 1990‐2009 (at 2010 dollars) 20 100 90 80 15 70 60 All ECCE workers 50 School‐based worker 40 Center‐based workers All ECCE workers 10 School‐based worker Center‐based worker Home‐based workers 30 Home‐based worker 5 20 10 ECCE industry turnover rate by sector, 1990‐2010 (% of workers who left the industry from one year to the next) 40 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 0 1992 0 Distribution of the ECCE workforce across sectors, 1990‐2010 (as a % of all ECCE workers) 60 50 30 40 All ECCE workers 20 School‐based worker School‐based worker 30 Center‐based worker Center‐based worker Home‐based worker Home‐based worker 20 10 10 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 0 1990 0 21 Table1.EvolutionoftheECCEworkforce,andcomparisontofemaleandlow‐wageworkers (1990‐2010) 1992 2010 2010 vs . 1992 Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment ECCE workers Les s tha n hi gh s chool 21.4 Hi gh s chool degree 31.5 Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree 26.1 At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 20.9 11.5 26.9 33.3 28.4 ‐9.9 ‐4.6 7.2 7.5 * * * * Female workers Les s tha n hi gh s chool Hi gh s chool degree Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 11.5 36.0 29.2 23.2 8.1 26.4 31.9 33.6 ‐3.4 ‐9.6 2.7 10.4 * * * * Low‐wage workers Les s tha n hi gh s chool Hi gh s chool degree Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 20.5 38.9 26.7 13.9 17.0 33.5 31.1 18.4 ‐3.5 ‐5.4 4.4 4.5 * * * * 1990 2009 2009 vs . 1990 Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) ECCE workers 10,746 Female workers 24,427 Low‐wage workers 18,266 16,215 30,629 21,298 51% * 25% * 17% * 11.7 19.0 14.2 33% * 17% * 6% * Mean hourly earnings of full‐year workers (at 2010 dollars) ECCE workers 8.8 Female workers 16.3 Low‐wage workers 13.4 Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employ ECCE workers 19.0 28.0 9.0 * Female workers 56.4 57.9 1.5 * Low‐wage workers 42.5 42.2 ‐0.3 Industry turnover rate ECCE workers Female workers Low‐wage workers 1990 2010 32.9 24.7 26.5 23.6 17.9 19.1 2010 vs . 1990 Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the workforce ECCE workforce enterers 37.6 42.3 Low‐wage workforce enterers 41.8 42.0 ‐9.3 * ‐6.8 * ‐7.4 * 4.7 0.2 * denotes change with respect to 1990 or 1992 is statistically significantly different from zero at the 5% level. Changes in the share of workers by educational attainment, the share with pension and/or health benefits, and the industry turnover rate are measured in percentage points; changes in annual and hourly earnings, as a percent change; and changes in the average occupational prestige score of those entering the ECCE workforce, in percentiles. Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 22 Table2.EvolutionoftheECCEworkforcebysector(1990‐2010) Center‐based workers 1992 2010 Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment Les s tha n hi gh s chool 12.3 Hi gh s chool degree 32.7 Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree 33.3 At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 21.6 1990 9.8 30.0 36.6 23.7 Home‐based workers 1992 2010 37.6 34.5 21.8 6.1 School‐based workers 1992 2010 19.8 * 30.9 34.3 * 15.0 * 5.3 20.6 17.5 56.6 5.1 12.0 * 21.7 61.2 2009 1990 2009 1990 2009 10,809 14,567 * 6,480 12,415 * 24,191 27,014 Mean hourly earnings of full‐year workers (at 2010 dollars) 9.2 10.9 * 5.6 8.9 * 17.5 18.2 Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employer 20.4 24.5 3.1 7.6 * 64.3 68.8 1990 2010 1990 2010 1990 2010 Industry turnover rate 34.0 24.4 * 36.9 28.5 * 15.9 13.6 Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the ECCE workforce 41.3 44.6 32.3 33.4 51.4 54.1 Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) * denotes change with respect to 1990 or 1992 is statistically significantly different from zero at the 5% level. Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 23 Table3.DecompositionoftheoverallchangesinthecharacteristicsoftheECCEworkforce(1990‐2010) Panel A Change attributable to changes in the characteristics of workers within the sectors Panel B Change attributable to changes in the distribution of workers across sectors Sector contributions to the part of the change attributable to changes in the characteristics of workers within the sectors Center‐based workers ‐8.8 ‐4.0 7.4 5.4 (65%) (84%) (84%) (58%) ‐4.7 ‐0.8 1.4 3.9 (35%) (16%) (16%) (42%) 12% 28% 19% 16% 2009 vs . 1990 Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) 42% Mean hourly earnings of full‐year workers (at 2010 dollars) Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employer School‐based workers 2010 vs . 1992 2010 vs . 1992 Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment Les s tha n high s chool Hi gh s chool degree Some col lege or As s ocia te's degree At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree Home‐based workers 88% 39% 73% 71% 0% 32% 8% 13% 2009 vs . 1990 (78%) 12% (22%) 37% 25% (72%) 10% (28%) 35% 60% 4% 4.3 (48%) 4.7 (52%) 41% 45% 14% 2010 vs . 1990 55% 8% 2010 vs . 1990 Industry turnover rate ‐8.1 (86%) ‐1.3 (14%) 53% 44% 4% Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the ECCE workforce 2.1 (49%) 2.1 (51%) 58% 28% 14% Changes in the share of workers by educational attainment, the share with pension and/or health benefits, and the industry turnover rate are measured in percentage points; changes in annual and hourly earnings, as a percent change; and changes in the average occupational prestige score of those entering the ECCE workforce, in percentiles. Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 24 REFERENCES Bassok,Daphna.2010.DoblackandHispanicchildrenbenefitmorefrompreschool? Understandingdifferencesinpreschooleffectsacrossracialgroups.ChildDevelopment81 (6):1828‐1845. Bassok,Daphna,MariaFitzpatrick,andSusannaLoeb.2012.Disparitiesinchildcare availabilityacrosscommunities:Differentialreflectionoftargetedinterventionsandlocal demand.WorkingPaper. Bellm,Dan,andMarcyWhitebook.2006.Rootsofdecline:Howgovernmentpolicy hasde‐educatedteachersofyoungchildren.Berkeley,CA:CenterfortheStudyofChild CareEmployment. Blau,David.1999.Theeffectofchildcarecharacteristicsonchilddevelopment.The JournalofHumanResources34(4):786‐822. Blau,David.2000.Theproductionofqualityinchildcarecenters:Anotherlook. AppliedDevelopmentalScience,SpecialIssue:Theeffectsofqualitycareonchilddevelopment 4(3):136‐149. Brandon,RichardN.,andIvelisseMartinez‐Beck.2006.Estimatingthesizeand characteristicsoftheUnitedStatesearlycareandeducationworkforce.InM.ZaslowandI. Martinez‐Beck(Eds.),Criticalissuesinearlychildhoodprofessionaldevelopment.Baltimore: Brookes. CommitteeonEarlyChildhoodCareandEducationWorkforce:AWorkshop, InstituteofMedicine,NationalResearchCouncil.2012.Theearlychildhoodcareand educationworkforce:Challengesandopportunities:Aworkshopreport.Washington,DC:The NationalAcademiesPress. Cost,QualityandOutcomesStudyTeam.1995.Cost,qualityandoutcomesinchild carecenters:Executivesummary.UniversityofColoradoatDenver,Departmentof Economics,CenterforResearchinEconomicandSocialPolicy. Currie,Janet,andMatthewNeidell.2003.GettinginsidetheblackboxofHeadStart quality:Whatmattersandwhatdoesn’t?NBERWorkingPaperNo.10091. Early,DianeM.,KellyL.Maxwell,MargaretBurchinal,SoumyaAlva,RandallH. Bender,DonnaBryant,KarenCai,RichardM.Clifford,CarolineEbanks,JamesA.Griffin, GaryT.Henry,CarolleeHowes,JenifferIriondo‐Perez,Hyun‐JooJeon,AndrewJ.Mashburn, EllenPeisner‐Feinberg,RobertC.Pianta,NathanVandergrift,NicholasZill.2007.Teachers' education,classroomquality,andyoungchildren'sacademicskills:resultsfromseven studiesofpreschoolprograms.ChildDevelopment78(2):558‐580. Elicker,James,CherylFortner‐Wood,andIleneC.Noppe.1999.Thecontextofinfant attachmentinfamilychildcare.JournalofAppliedDevelopmentalPsychology20:319–336. Fuller,Bruce,SusanD.Holloway,XiaoyanLiang.1996.Familyselectionofchild‐care centers:Theinfluenceofhouseholdsupport,ethnicity,andparentalpractices.Child Development67(6):3320‐3337. 25 Fuller,Bruce.2008.StandardizedChildhood:ThePoliticalandCulturalStruggleover EarlyEducation.Stanford,CA:StanfordUniversityPress. Hamre,BridgetK.,andRobertC.Pianta.2006.Student‐teacherrelationships.InG.G. Bear,&K.M.Minke(Eds.),Children’sNeedsIII:Development,PreventionandIntervention (pp.59‐71).Bethesda,MD:NationalAssociationofSchoolPsychologists. Harris,DouglasN.,andScottJ.Adams.2007.Understandingthelevelandcausesof teacherturnover:Acomparisonwithotherprofessions.EconomicsofEducationReview26: 325–337. Herzenberg,Stephen,MarkPrice,andDavidBradley.2005.LosingGroundinEarly ChildhoodEducation:DecliningWorkforceQualificationsinanExpandingIndustry,1979‐ 2004.EconomicPolicyInstitute. Howes,Carollee,DeborahA.Phillips,andMarcyWhitebook.1992.Thresholdof quality:Implicationsforthesocialdevelopmentofchildrenincenter‐basedchildcare.Child Development63:449‐460. Kagan,SharonLynn,KristieKauerz,andKateTarrant.2008.TheEarlyCareand EducationTeachingWorkforceattheFulcrum:AnAgendaforReform.NewYork,NY: TeachersCollegePress. Knudsen,EricI.,JamesJ.Heckman,JudyL.Cameron,andJackShonkoff.2006. Economic,neurobiological,andbehavioralperspectivesonbuildingAmerica’sfuture workforce.ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciencesoftheUnitedStatesofAmerica 103(27):10155‐10162. Liang,Xiaoyan,BruceFuller,andJudithD.Singer.2000.Ethnicdifferencesinchild careselection:Theinfluenceoffamilystructure,parentalpractices,andhomelanguage. EarlyChildhoodResearchQuarterly15(3):357–384. Nam,CharlesB.2000.Comparisonofthreeoccupationalscales.Unpublishedpaper. CenterfortheStudyofPopulation,FloridaStateUniversity. Nam,CharlesB.,andMonicaBoyd.2004.Occupationalstatusin2000:Overa centuryofcensus‐basedmeasurement.PopulationResearchandPolicyReview23:327–358. NationalScientificCouncilontheDevelopingChild.2004.Youngchildrendevelopin anenvironmentofrelationships.WorkingPaper1. NationalScientificCouncilontheDevelopingChild.2007.Thetimingandqualityof earlycareexperiencescombinetoshapebrainarchitecture.WorkingPaper5. NICHDEarlyChildCareResearchNetwork.2000.Characteristicsandqualityofchild carefortoddlersandpreschoolers.AppliedDevelopmentalPsychology4(3):116‐135. Peisner‐Feinberg,EllenS.,MargaretR.Burchinal,RichardM.Clifford,MaryL.Culkin, CarolleeHowes,SharonLynnKagan,andNoreenYazejian.2001.Therelationofpreschool child‐carequalitytochildren’scognitiveandsocialdevelopmenttrajectoriesthrough secondgrade.ChildDevelopment72:1534‐1553. 26 Ronfeldt,Matthew,HamiltonLankford,SusannaLoeb,andJamesWyckoff.2011. HowTeacherTurnoverHarmsStudentAchievement.NationalBureauofEconomicResearch WorkingPaperNo.17176. Saluja,Gitanjali,DianeM.Early,andRichardM.Clifford.2002.Demographic characteristicsofearlychildhoodteachersandstructuralelementsofearlycareand educationintheUnitedStates.EarlyChildhoodResearchandPractice4: http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v4n1/saluja.html. Shonkoff,JackP.,andDeborahA.Phillips.2000.FromNeuronstoNeighborhoods. TheScienceofEarlyChildhoodDevelopment.Washington,DC:NationalAcademyofPress. Torquati,JuliaC.,HelenRaikes,CatherineA.Huddleston‐Casas.2007.Teacher education,motivation,compensation,workplacesupport,andlinkstoqualityofcenter‐ basedchildcareandteachers'intentiontostayintheearlychildhoodprofession.Early childhoodresearchquarterly22(2):261‐275. Tout,K.,Starr,R.,Soli,M.,Moodie,S.,Kirby,G.,&Boller,K.2010.Thechildcare QualityRatingSystemassessment:CompendiumofQualityRatingSystemsandevaluations. Washington,D.C.:OfficeofPlanning,ResearchandEvaluation. Tran,Henry,andAdamWinsler.2011.Teacherandcenterstabilityandschool readinessamonglow‐income,ethnicallydiversechildreninsubsidized,center‐basedchild care.ChildrenandYouthServicesReview33(2011):2241–2252. U.S.DepartmentofEducation,andU.S.DepartmentofHealthandHumanServices. 2011.RacetotheTop–EarlyLearningChallenge2011.GuidanceandFrequentlyAsked Questions.Availablefromhttp://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop‐ earlylearningchallenge/guidance‐frequently‐asked‐questions.pdf U.S.CensusBureau.2010.HistoricalTable.PrimaryChildCareArrangementsof PreschoolerswithEmployedMothers:SelectedYears,1985to2010.Availablefrom http://www.census.gov/hhes/childcare/data/sipp/index.html. U.S.CensusBureau.2006.CurrentPopulationSurveyDesignandMethodology. TechnicalPaper66. Vandell,DeborahLowe,andBarbaraWolfe.2000.Childcarequality:Doesitmatter anddoesitneedtobeimproved?InstituteforResearchonPoverty,SpecialReport78. Whitebook,Marcy,LauraSakai,EmilyGerber,andCarolleeHowes.2001.Thenand now:Changesinchildcarestaffing,1994‐2000(TechnicalReport).CenterfortheChildCare Workforce,Washington,DC,andInstituteofIndustrialRelations,UniversityofCalifornia, Berkeley. Whitebook,Marcy,andLauraSakai.2003.Turnoverbegetsturnover:an examinationofjobandoccupationalinstabilityamongchildcarecenterstaff.Early ChildhoodResearchQuarterly18:273–293. 27