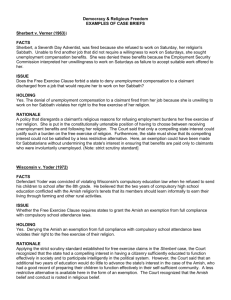

Religion and the Family: The Case of the Amish James P. Choy

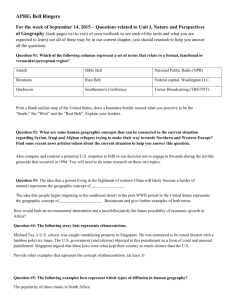

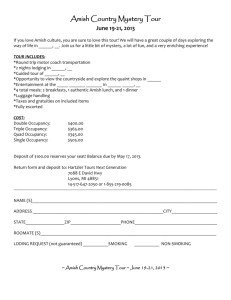

advertisement