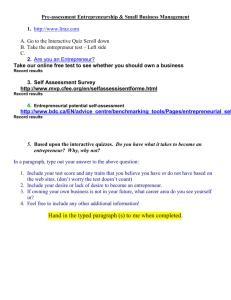

SURVIVAL OF THE SMALL FIRM AND THE ENTREPRENEUR

advertisement