Document 12315296

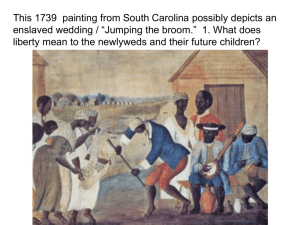

advertisement