Employers Skill Survey: Case Study Health and Social Care

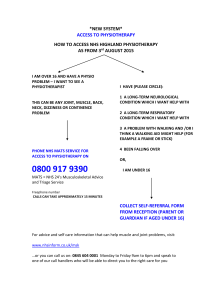

advertisement