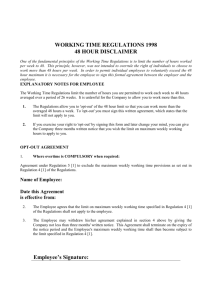

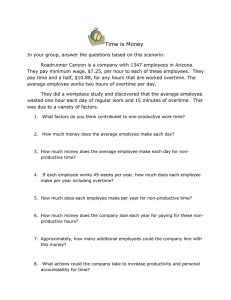

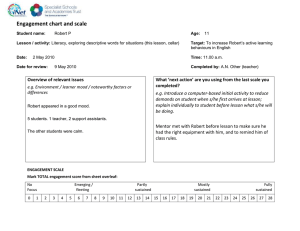

The business context to long hours working EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS

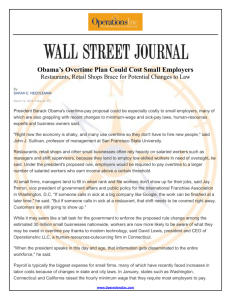

advertisement