DEVELOPING CAREER TRAJECTORIES IN ENGLAND: THE ROLE OF EFFECTIVE GUIDANCE

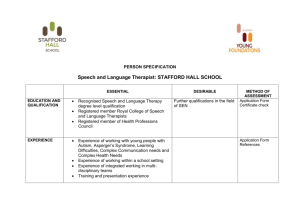

advertisement