UK approaches to Skill Needs Analysis and Forecasting:

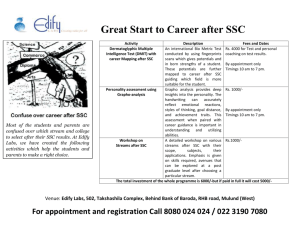

advertisement