Research Report D W P

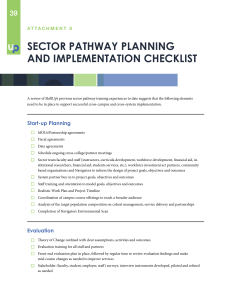

advertisement