Methodological Issues in Estimating the Value Added of Further Education,

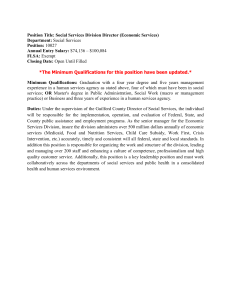

advertisement