The Value of Vocational Education Policy Research Working Paper 5035

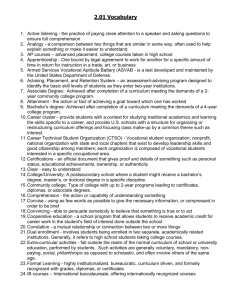

advertisement