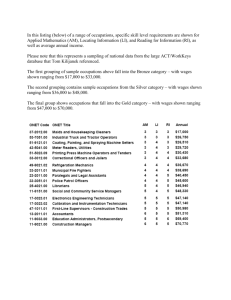

Allied Health A Supply and Demand Study 2010

advertisement