Socrates Grundtvig Project Learning in Higher Education: improving practice for non-traditional students

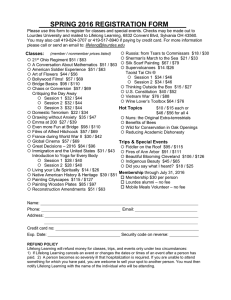

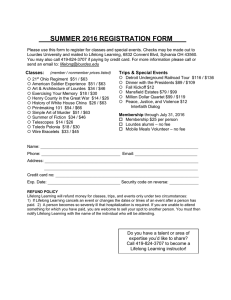

advertisement