W O R K I N G Serving the Underserved

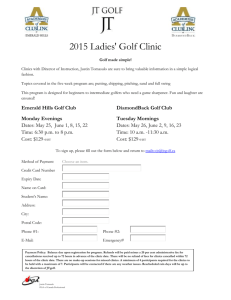

advertisement