History 372 / American Cultural History since 1865

advertisement

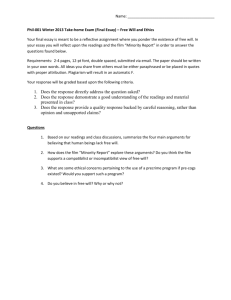

History 372 / American Cultural History since 1865 “We’re off to see the Wizard” Spring 2011 • University of Puget Sound General Info Instructor: Doug Sackman • Office: Wyatt 138 email: dsackman@ups.edu phone: x3913 • Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays: 1.15-2.15pm (I am also available to meet with you at other times; just email me for an appointment) webpage: http://www.pugetsound.edu/faculty-sites/doug-sackman/ 1 Introduction The title of this course raises a thick, tangled set of questions—an unruly garden springing from the roots of the United States as a nation that proclaims as its motto “e pluribus unum” (out of many, one). Is there now or has there ever been one American culture? Variations on this question have been asked over and over again—at least since Hector St. John de Crevecoeur asked “What is this new man, the American?”—and a variety of different answers have been put forward over time. A new scholarly enterprise was born after World War II—an interdisciplinary field combining history, literature and other disciplines called American Studies—in order to search for “the American mind” or the “American character.” In more recent decades, many American Studies scholars have abandoned the quest to find the American character as at once quixotic and misguided, and have instead embraced the idea that America has always encompassed many cultures at any given period—even though they may identify an ascendant, dominant or “hegemonic” culture in a particular period, they acknowledge that even these have been contested and alternative cultures have always existed at the margins of and often in tension or conversation with some purported “mainstream” American culture. The search for American culture—however it is conducted and whatever discoveries are made—begs a further question, what is culture? What are we looking for? “Culture” is a complicated term, with a surprising history of its own. Until well into the 19th century, only the elite were thought to have culture, and it was often conceived of as a close relative of “civilization.” With the advent of modern, relativistic anthropology in the early 20th century (following the work of Franz Boas and others), “culture” gained a new, democratizing definition—everyone was understood to have a or live in a “culture,” which the anthropologists thought of as a way of life expressed in daily rituals and behavior, material objects, laws, stories and legends and so on. Many other terms have been used to describe different types of culture, including the important distinctions between “high” and “low” culture (or highbrow, lowbrow, and middlebrow culture); between “mass culture” and “folk culture”; between “mainstream culture” and “ethnic culture.” Culture has been combined with modifiers to reflect the diversity of the American scene, so that we talk about black, white, Asian American, Latino, and [insert others] culture; about women’s and men’s culture; about Southern culture or Western culture; about youth culture or surf culture. Some Americans have even selfconsciously tried to create and live within what they called a counterculture. 2 It may be useful at the outset of the course to look at a “taxonomy” of the different phenomena American cultural historians have had in mind when they explore culture.1 These include, among others, seeing culture as: a. a form or style of artistic expression (e.g. the blues in music or Abstract Expressionism in art) b. as any social or institutional sphere in which collective forms of meaning are made, enforced, and contested. This definition can point us to museums, publishing houses, amusement parks, or a film studio, and, more broadly, any group of people in a place that generate their own values, rules of behavior, and collective symbols. c. as a common set of beliefs, customs, values, and rituals (this is the “anthropological” concept of culture). d. as a semiotic or discursive system—the collection of signs, symbols and stories that constitute “discourses” and which shape meaning and ultimately experience, identity and our sense of reality and truth e. as transnational or global circulation (i.e. something that travels across borders with people and their goods). This conceptualization of culture points to the interplay between immigrant cultures and the nation state, and the nation as an “imagined community” and other communities with which it has exchanges and “conversations”. Whatever “culture” cultural historians are looking at or for, and however they conceive of it, they are generally concerned with different kinds of phenomena that other kinds of historians (such as political or economic historians, though there often has been an overlap2). Cultural historians tend to be concerned with language, identity, and representations. They see historical significance the acts of meaning-making as they occur in daily life and through media of all kinds. They are interested in subjective experience, in ideas and values, and in the power of symbols. They explore how the circulation of ideas and symbols through various media both reflect and shape culture. In the wake of the work of the influential theorist Marshall McLuhan, they consider how the “medium is the message.” One way of thinking about this famous formulation for our purposes is this: is our culture(s) what we are as America and Americans, and if so, just how? The following definitions are derived from James Cook and Lawrence Glickman, “Twelve Propositions for a History of U.S. Cultural History,” in Cook, Glickman and Michael O’Malley, eds., The Cultural Turn in U.S. History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). 1 In fact, after the so-called “cultural turn” in history and the humanities in the 1980s, other fields began to embrace a cultural approach to their topic (such as with the proliferation of cultural interpretations of American foreign relations and empire building). 3 2 At some point, we also need to bracket off discussion and debates about definitions of “culture”, and look at manifestations of the thing itself. As T.S. Eliot wrote in his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,”: “Do not ask ‘what is it?’ Let us go and make our visit.” Themes and Format Regrettably, it is not possible to visit all aspects and facets of America culture since 1865 (going just with definition “a” of culture above, one could devote an entire course to the history of popular music in America—or even a particular genre, such as jazz or punk rock or hip hop). Obviously, we will not be able to map all of American culture/s from 1865-present, though participants will be able to explore some areas of interest beyond what is currently represented on the syllabus through their presentations, final paper and their work in teams designing our day’s work for four of our sessions over the term. Students will thus be creating part of the syllabus and the course itself. Though the course readings themselves are varied, there will be a particular focus on the rise and spread of “consumer culture”—and how it has been received and contested—from the early 20th century to the present. We will also attend to the construction of gendered, racial, and class-based identities over time, and to the relationship between culture and other aspects of American history (including politics). Major themes of the course include: 1. The Rise and Transformation of Consumer Culture as Contested Embodiment of the American Dream 2. Race, Gender, and Class Identity in relation to Cultural Production and Reception 3. The Constitutive Role of Media in Forming and Reforming American Identities Participants in the course will extend the range of topics explored through their in-class presentations and through their team-led seminar day. The fact 4 that participants will bring their own interests to the table to enrich the course reflects its general orientation. Indeed, the course is meant to be a collaborative investigation. Class time will be devoted largely to discussions of the readings and other texts and the issues they touch upon. I’ve designed the course to give u a range of opportunities to participate in the class and contribute to its content and character. Of course, you are encouraged to actively engage with discussions, raising questions, making points and otherwise contributing to the flow of the conversation. Note that the reading load for this course is heavy and in a few cases involves material that is quite dense. The readings for the course are extensive, and essential. Your reactions to the content, ideas and evidence presented in the reading will be crucial to what we do in class. Doing the reading in time for class is thus critical to the success of the course. In reading selections, you will find it useful to take notes and write down particular questions you might have or topics you would like to discuss. As a student, I found that underlining or highlighting passages, while helpful, was not the best way to prepare me to participate in class discussions. I started to take notes on a separate sheet of paper (or on my computer), listing the relevant page number on the left and then some idea or quote that I found interesting next to it. In class, then, I could use this as an index of my ideas, and then point to a particular passage as a basis for a question or to present my perspective on a particular issue. You may find that developing a notetaking system will work for you. Please bring the readings to class on the day for which they are assigned. If you do not do the readings, you will get little out of the class. If you do the readings, but have nothing to say about them, then the class as a whole will suffer. The more you get involved, the more you will get out of the class, and the more exciting, engaging, and successful the class will be as whole. Readings and Texts: 1. T.J. Jackson Lears, Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877-1920 2. Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920-1940 3. John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath 4. Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America 5 5. Susan Douglas, The Rise of Enlightened Sexism: How Pop Culture Took Us from Girl Power to Girls Gone Wild 6. A variety of articles and documents posted on Moodle 7. Films will be regularly screened on Tuesdays; discussion of the film will usually take place on the following Thursdays. The films will be treated as important primary texts in the class, and “read” in their cultural and historical context. The films will be considered as embodiments and shapers of popular culture, as well as significant commentaries upon American culture. Course Requirements 1. Participation, Attendance, Short Papers. This category includes reading, attendance, participation in discussions and several short papers and a document gathering assignment. Students can participate in class by making points and connections, raising questions, listening and responding to the comments of other students, and otherwise engaging with the flow of the discussion. Short writing assignments, which will not be given a letter grade but will be assigned a number from 0-4 that assesses their general quality, include: a. 5 1-2-page Discussion Papers (explained below) b. 4 film discussion papers (explained below) c. 1 document gathering assignment (explained in the syllabus schedule) A variety of other short assignments for class preparation may also be required. Active listening as well asking questions and making comments are integral parts of class participation. Regular attendance is expected (more than three unexcused absences will begin to severely impact your participation grade, and further absences will eventually lead to a withdrawal from class). (25%) 2. In class Presentation. A short (7-10 minute) in-class presentation, on a topic related to US Cultural History since 1865. Examples of what you might select include, but are not limited to, a particular cultural artifact (e.g. a painting, a song, a novel, a building, etc), an “artist” (broadly construed) who is significant in some way (e.g. Louis Armstrong, Louis Sullivan, Ice Cube, Jackson Pollock, Elvis Presley, Walt Disney, etc.), an artistic genre (e.g. Grunge, or Realism), some aspect of a medium (such as television, radio, mass circulation 6 magazines, the internet), an event understood culturally (such as the Scopes Trial), or a significant or revealing American icon, symbol, or celebrity. Guidelines for the presentation will be distributed, and students should select a topic by the end of the second week of classes. Presentations will then be scheduled on days throughout the term. (5%) 3. Interpretive essay I: a 5-7 page paper due in Week 7; guidelines will be distributed. (21%) 4. Interpretive essay II, a 5-7 page paper due in Week 12; guidelines will be distributed. (21%) 5. Final Project: research essay. A 7-10 page paper on a topic relevant to the course, making use of both primary and secondary sources. A prospectus for your final project is due in week 13 and the final project is due Wednesday of Finals Week. Guidelines will be distributed after week 9. (25%) 6. Team led class session. Working in teams, students will plan and lead one day of the seminar. Each team will select a topic for their day related to American cultural history in a particular period, select appropriate scholarly readings and documents, and lead the class session. (3%) Note on Quiz Possibilities: depending on the quality of class discussions and the collective sense of how thoroughly and completely the reading is being done, we may need to add quizzes or other assignments to the course itinerary (in which case, the percentage weight of some of the above categories will be reduced to make room for the quizzes, etc). Grading Policies The work in all of the above categories will be taken into account to determine your final grade. In general, the writing asks you to go far beyond the recitation of facts and information. You will be formulating your own ideas and arguments, gathering and organizing evidence to support your positions, and putting it all together in finished essays that are at their best polished, engaging, original, creative, and/or provocative. I will distribute more specific criteria that I use in evaluating your longer papers. The Discussion Papers are more informal in orientation, and one of their purposes is to allow you to pursue your ideas and hone your writing talents without the pressure of grades. The following statements will give you some idea what level of work and participation constitutes what kind of grade in this course: 7 Work that is of D-level or below does not rise to the standards of expectations in the class, which are reflected in the description of C-level work. C-level work is considered both average and respectable in this course. Work that merits a C represents a serious engagement with the class and the course materials by the student. For papers, this means that the paper deals with its topic, makes use of the proper number and type of sources, shows that the student has grappled with the readings and issues, and advances a central idea or thesis. Yet, the thesis may be vague and there may be problems with the mechanics, organization or clarity of the paper. In terms of participation, the C-level student regularly attends, is attentive to what is going on in the classroom, occasionally offers ideas and perspectives in class, completes the Prep Papers in satisfactory fashion, and willingly contributes to small group discussions. B-level work is very good. It represents both serious engagement with and reasonable mastery of the course material. The B-level student maintains their degree of engagement throughout the course, and usually their work shows improvement. Papers that merit a B are well-crafted and organized, advance a central thesis that addresses the paper’s topic in an interesting or illuminating fashion, are mostly free from mechanical and grammatical errors, draw effectively on a range of materials, and are generally persuasive and cogent in their argument. B-level participation involves regular attendance and participation in class discussions. Comments and contributions are often based on a careful consideration of the readings. For example, such a student may sometimes point to a specific passage in the text to back up or develop their comment or question. A-level work is exceptional. Not only do A-level papers display all of the good qualities of a B-paper, their central argument is advanced with an exceptionally impressive degree of sophistication, originality or insight. The paper’s organization, craft and use of evidence are all excellent. In terms of participation, contributions to class discussions are both frequent and particularly insightful. Late Policy: Assignments that are up to 24 hours late will receive a 1/3 grade reduction (e.g. a B would become a B-); assignments turned in more than one but less than two days late will be lowered 2/3 of a grade; work turned in three days late will be lowered a full grade; work turned in beyond threedays late will be lowered a 1 and 1/3rd grade. 8 Academic Honesty Faith in your academic integrity is vital to all we do at Puget Sound. It should go without saying that the college expects that all work submitted for evaluation in courses will be the product of the student’s own labor and imagination. Of course, you are free to speak with others about your work and share ideas and perspectives. In writing your papers, though, you are developing your own ideas and arguments. You can incorporate the ideas or words of others in your own paper, but to do so you must properly cite your sources. Turning in a paper that attempts to pass off the words or ideas of others as your own constitutes plagiarism (see The Logger for more information). Like other forms of cheating, plagiarism is a contamination that pollutes our environment. Students who knowingly turn in work that involves plagiarism or is marred by other forms of cheating will not pass the course, though more severe penalties may be recommended for egregious cases. One can understand the temptation to turn in illegitimate work: students working under intense pressures may turn to cheating as an easy way out. But to do so, you not only steal the work of others, you cheat yourself and your fellow students as well. A real degree from UPS cannot be obtained through looting. If you are worried about your grade or completing an assignment, please come and talk to me. I can work with you to help you get over the hurdles and make it possible for you to get something positive out of the course. Discussion Papers The class is divided into 5 “groups”—A, B. C, D & E. (This is basically for the purpose of dividing up the class—you will be writing your discussion papers individually, not in groups). Discussion Papers for your group are due on the days indicated in the course schedule with your group's letter in brackets next to the date (see below). Under no circumstances, including computer failure, may Discussion Papers be turned in late, since their purpose is to be available for use in the class discussion on the day on which they are due. (In certain circumstances, I may allow you to switch the day for which you write a discussion paper, but you must ask me about this at least 24 hours in advance). Discussion Papers should be typed and between 1 and 2 pages long. Your group in scheduled on 6 days; you may skip one day (i.e., you just need to write a discussion paper for 5 of the 6 days on which your group is indicated). The Discussion Papers involve two components: a topic discussion and an issue identification: 9 Topic Discussion: For the topic discussion, I would like you to write 3-4 paragraphs or so about some aspect of the reading for that day that grabs your attention and you would like to discuss. I am not looking for you to summarize the reading. Instead, I would like you to identify some theme or issue raised in the reading and interpret its significance. You need not deal with the reading as a whole; in fact, you may want to focus on a small part of the larger reading. You may wish to draw comparisons between the readings of the day, or between the reading of the day and previous readings. You may wish to discuss how the reading relates to some larger issue in the class. You must include at least one quotation from the reading in your paper (normally, stronger papers use such citations). Please provide the page number in a footnote or in parentheses for your quotations. I will on occasion ask you to summarize or read your topic discussion for the class. Issue ID: The second component of the Discussion Paper is the identification of some issue that can be suitable for class discussion. This can be one or two sentences long, and it can be as simple as identifying a quote from one of the readings that you find illuminating and interesting or questionable and briefly stating what important issue you see in the quote. You might also raise a point of comparison between readings. The issue may be related to your topic discussion, though it need not be. Be prepared with these: I will on occasion ask you to present your issue id in class as a way to start discussion. Film Discussion Papers: These should roughly follow the format above for the discussion papers, with both a topic discussion and an issue id. You may wish to highlight particular scenes in the film under discussion. You are also welcome to make connections to readings in the course. You are asked to write four of these over the course of the term, and you should do at least 2 of them before Spring Break. Film discussion papers are due in class on the Thursday following the film screening. Course Schedule The reading for each day is listed under that day’s number on the schedule (e.g. 2.1=Tuesday of the second week; 2.2= Thursday of the second week, and so on. Bulleted readings (•) are from the books; readings that are posted on Moodle are designated with an ∑. Groups that have a discussion paper due on the readings for that day are noted in the brackets after the date, as is the day that your group has its document gathering assignment 10 due. Days with an asterisk (*) indicate those Tuesdays in which there is no screening of a film in the 5-7pm slot. Part I: The Advent of Modernity as a Crisis and Rebirth of American Culture Week 1 (week of January 18-) 1.1 Introduction: The Wizard of Oz as Allegory and Embodiment of American Culture and History ° Key discourses: What have scholars and others said about “culture,” “American culture,” and “cultural history”? ° Interpretive smackdown: Littlefield’s OZ versus Leach’s OZ (handout) 1.2 [Groups A and B]: • Lears, Rebirth of a Nation, introduction, chapters 1 and 2 ∑Documents: excerpts from Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” (1893); Theodore Roosevelt, “The Strenuous Life” (1899), Jane Addams, “The Subjective Necessity of Social Settlements” (1892), Andrew Carnegie “Wealth” (1899) Week 2 (Jan 25-) 2.1 [Group C] • Rebirth, chapter 3 ∑ Josiah Strong, from Our Country (1885), Booker T Washington, “The Atlanta Compromise” (1885), John Hope, “A Critique of the Atlanta Compromise” (1896) excerpt from Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) Film Screening: Birth of a Nation (DW Griffith, 1915) [end of part 1 and part 2] The story deals with a northern family, the Stonemans, and a southern family, the Camerons, friends who are divided by the Civil War. The youngest sons from each family meet on a Civil War battlefield, where they die melodramatically. The first section ends with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. 2.2 [Group D] ∑ Readings on Birth of a Nation ∑ Suzan Lori Parks, “The America Play” ∑ excerpt from Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory Week 3 (Feb 1-) 11 3.1 [Group E] • Lears, chapters 4 and 5 ∑ Upton Sinclair, excerpt from The Jungle (1906); Henry Adams, “The Columbia Exposition of 1893”; “Pullman Strikers Statement” (1894); William Jennings Bryan, from The Cross of Gold Speech (1896) film: Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936) 3.2 [Group A] • Lears, chs. 6 and conclusion ∑ Frederick Winslow Taylor, “Scientific Management,” (1912); George Creel, “How We Advertised America” Part II: Advertising, Media, and Consumer Culture, 1920-1940 Week 4 (Feb 8-) * 4.1 Film: Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941); screened in regular class time 4.2 [Group B] • Marchand, Advertising the American Dream, chapter 1 and 3 & pp. 88-94 ∑ excerpt from Denning, The Cultural Front, 362-365; 370-394 ∑ excerpt from Czitrom, Media and the American Mind Week 5 (Feb 15-) * 5.1 [Group C] [Document Gathering Assignment for Groups A and D only: Reading an Advertisement from a Mass Circulation Magazine, before 1940: locate, reproduce, and analyze a particular advertisement from a mass circulation magazine: For the document gathering assignment, I would like you to locate an advertisement in a popular magazine (such as Life, Time, Newsweek, Fortune, or American Magazine [this stopped in the 1950s)—we hold all of these in the library (in the basement), photocopy it, and write a paragraph interpreting its significance. You may wish to focus on how the ad tries to encourage the reader to purchase the product and/or on how the ad reflects the culture of its day.] • Marchand, Advertising, chs. 5-7 Brown and Haley Lectures: Feb 15 at 6.30pm in the Rotunda and Feb 16 at 6.30pm in Kilworth; Melanie Burford, Pulitzer Prize winning photojournalist, will speak on photography and 12 Gulf Oil Spill and Hurricane Katrina. You are required to attend one of the lectures, and encouraged to attend both. 5.2 [Group D] [Document Gathering Assignment for Groups C, B and E: Reading an Advertisement from a Mass Circulation Magazine: locate, reproduce, and analyze a particular advertisement from a mass circulation magazine; Group C—please find an ad from 1940-1950; B look for one from 1950-1960; E look for one from 1960-1970] • Advertising the American Dream, chs. 9 and 10 in class: Mercury Theater’s Lincoln Week 6 (Feb 22-) *6.1 [Group E] Teaching Team 1 ∑ readings selected by Team 1 Part III: Contesting the Promise of Modernity through the Depression 6.2 [Group A] ∑ Harlem Renaissance documents Week 7 (March 1-) <Paper 1 due Monday by 3pm; please turn in a hard copy to the folder outside of my office> Spike Lee on Campus! 7.30pm in the Fieldhouse (get tickets in advance) 7.1 [Group B] • Grapes of Wrath, chs. 1-11 ∑ excerpt from James Agee and Walker Evans, Let us Now Praise Famous Men ∑ excerpt from Denning, The Cultural Front, on Disney’s animators Film: Sullivan’s Travels (Preston Sturges, 1941) 7.2 [Group C] • Grapes of Wrath, chs. 12-18 ∑ excerpt from Denning, The Cultural Front; Gregory, An American Exodus Week 8 (March 8-) 8.1 [Group D] 13 • Grapes of Wrath, chs. 19-24 Film: Stagecoach (John Ford, 1939) 8.2 [Group E] • Grapes of Wrath, chs. 25-end Spring Break: March 12-20 Part IV: Postwar America: Creating and Busting the Bonds of Consumer Conformity Week 9 (March 22-) 9.1 [Group A] Teaching Team 2 ∑ Readings selected by Team 2 Film: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegal, 1956) 9.2 [Group B] • Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic, introduction and chapter 2 Week 10 (March 29-) 10.1 [Group C] • Cohen, Consumers’ Republic, chs. 3 and 4 Film: Rebel without a Cause (Nicolas Ray, 1955) 10.2 [Group D] • Cohen, Consumers’ Republic, chs 5 and 6 ∑ selection from Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era ∑ selection from Barbara Ehrenreich, Hearts of Men ∑ selection from Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums Week 11 (April 5-) 11.1 [Group E] Teaching Team 3 ∑ Readings selected by Teaching Team 3 ∑ Alan Ginsberg, “Howl” Film: Howl (2010) + part of Atomic Cafe 14 11.2 [Group A] • Cohen, Consumers’ Republic, ch 7, and pp. 367-410. Week 12 (April 12-) 12.1 [Group B] ∑ selection from Thomas Frank, Conquest of Cool, chs. 1, 6 and 7 ∑ Alice Echols, "Across the Universe: Re-thinking Narratives of Second-Wave Feminism," In Between the Lines Press: New World Coming: The Sixties & the Shaping of Global Consciousness. In class: portion of Berkeley in the 60s Film: Across the Universe (Julie Taymor, 2007) or Forrest Gump (1994) 12.2: No class (I am away at the American Society for Environmental History Conference) < Paper 2 due Friday by 5pm> Part V: Race, Gender and the Cultural Logics of America in the Late 20th Century and the New Millennium Week 13 (April 19-) 13.1 [Group C and D] ∑ Jeffrey Ogbar, selections from Hip Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap ∑ Tricia Rose, from Black Noise and Queen Latifah statement ∑ George Lipsitz, “Cruising around the Historical Bloc: Postmodernism and Popular Music in East Los Angeles” Film: Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989) 13.2 [Group E and A] • Susan Douglas, The Rise of Enlightened Feminism, Introduction, chs. 1 and 2 <Friday by 5pm: prospectus for final project due> Week 14 (April 26-) 14.1 [Group B] Teaching Team 4 ∑ selections from Team 4 15 Film: class choice (American Beauty, Little Miss Sunshine, Clueless or something (possibly a TV show episode) from the 1990s or 2000s that fits in with current course themes) 14.2 [Group C] • Douglas, The Rise of Enlightened Sexism, chs. 3, 6-8 Week 15 (May 3-) 15.1 [Groups D and E] • Douglas, Rise of Enlightened Sexism, 9-epilogue Recommended: Frederic Jameson, “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”, Jean Baudrillard, “Simulation and Simulacra,” or Neal Gabler, Life: The Movie 16 Elijah Wald, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music (New York, NY: 2009) Ch. 17 “You Say You Want A Revolution” AHR Forum on “Popular Culture and its Audience,” The American Historical Review, 97.5 (December 1992), 1359-1408, 1417-1430 17