History 368 / The Course of American Empire:

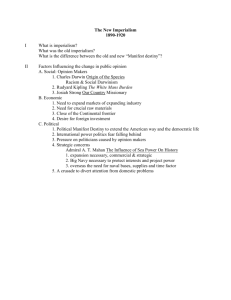

advertisement

History 368 / The Course of American Empire: The United States in the West & in the Pacific, 1776-1919 "Mayou Volcano, and Old Glory, Philippines", stereopticon image [1996.0009.KU24389], n.d., from Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside "As we came on deck we beheld rising before us on the edge of the water, the volcano Mayou, which is nearly 10,000 feet height. This volcano is very perfectly shaped, the cone culminating in a point, from which issues a large column of smoke; streams of lava wend their way downward. To the left is the city of Lagaspi, and there a regiment was landed. The gunboats shelled the shore, driving the Filipinos back." –Herbert Kohr, Around the World with Uncle Sam (1907), p. 112. Westward the course of empire takes its way; The four first Acts already past, A fifth shall close the Drama with the day; Time's noblest offspring is the last. —Bishop Berkeley, "America: A Prophecy," 1726 1 "[Imperialism is a] determination to expand geographically and economically, imposing an alien will upon subject peoples and commandeering their resources". ––Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford 2007). General Info Instructor: Doug Sackman • Office: Wyatt 138 email: dsackman@ups.edu phone: x3913 • Office Hours: Tuesdays: 10-11.30; Fridays 11-11.50am (I am also available to meet with you at other times; just email me for an appointment) Introduction In recent decades, American historians have reconsidered the relationship of the United States to imperialism, and in the process questioned the longstanding belief that American national policy has normally been isolationist until after World War II, interrupted only by brief departures during the Spanish American War and World War I. Westward expansion has been reconsidered as continental conquest, in which both Indian peoples and Mexicans were conquered and colonized. U.S. foreign relations with Japan and China in the 19th and early twentieth centuries, and its colonial policies in Hawai’i and the Philippines, certainly undermine the notion that the United States has historically been an exceptionally isolationist national power. In this course, we will explore the politics and culture of United States imperialism from the nation's founding until the 1910s. Focusing on westward expansion and the projection of U.S. power into the Pacific, we will consider how the ideas and policies supporting expansion and military conquest were developed, expressed, manifested, and contested. We will also explore how various peoples have confronted U.S. colonialism, including Indians, Mexicans, Chinese, Hawaiians and Filipinos. Reading documents from the period as well as differing interpretations by historians, we will also examine the economic underpinnings of expansion, its environmental impact, and the racial ideas that were paradoxically used both to justify and to criticize imperialism. 2 While the course considers anti-imperialist ideas that were expressed at various times by leaders and citizens, it is not meant to be a primer in antiimperialism. Rather, students should learn to situate expansionistic policies and practices within their intellectual, political, cultural, military, and economic contexts. The course will also allow for a close examination of the different ways through which colonized peoples have resisted or accommodated U.S. imperialism. Major themes of the course include: 1. Empire and National Identity: We will explore the idea of empire as it has been debated politically beginning with the nation's founding, looking at the ways in which imperialism and democracy have been seen as opposing or potentially complementary ideals. 2. Race: Changing ideas of race have undoubtedly played a key role in shaping US encounters with foreign peoples. But while many historians have argued that racism aided and abetted imperialism, others have posited that racial ideas formed a strong basis of opposition to expansionism. 3. Gender: How has imperialism been represented in gendered terms? In what ways have ideas of masculinity and femininity been used to explain and justify conquest? 4. Confronting American Colonialism: How have the people who have stood in the path of US expansionism reacted? What are the particular dynamics under which US power has been resisted or accommodated? What have been the particular colonial policies designed to incorporate conquered peoples into the nation, as either equals or subordinate members? Readings: 1. Walter Nugent, Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansion, 2. Miller and Patterson, eds. Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, Vol. 1, 6th edition. 3. Paul VanDevelder, Savages and Scoundrels: The Untold Story of America’s Road to Empire through Indian Territory 4. Mathew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917 3 5. Noenoe Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism 6. History 368 Course Reader Format and Objectives In the above description, I have emphasized what “we” will do. I mean that: the course is meant to be a collaborative investigation. Class time will be devoted largely to discussions of the readings and the issues they touch upon. I’ve designed the course to give you a range of opportunities to participate in the class and contribute to its course. Of course, you are encouraged to actively engage with discussions, raising questions, making points and otherwise contributing to the flow of the conversation. Note that the reading load for this course is heavy and in some cases involves material that is quite dense. The readings for the course are extensive, and essential. Your reactions to the content, ideas and evidence presented in the reading will be crucial to what we do in class. Doing the reading in time for class is thus critical to the success of the course. In reading selections, you will find it useful to take notes and write down particular questions you might have or topics you would like to discuss. As a student, I found that underlining or highlighting passages, while helpful, was not the best way to prepare me to participate in class discussions. I started to take notes on a separate sheet of paper (or on my computer), listing the relevant page number on the left and then some idea or quote that I found interesting next to it. In class, then, I could use this as an index of my ideas, and then point to a particular passage as a basis for a question or to present my perspective on a particular issue. You may find that developing a note-taking system will work for you. Please bring the readings to class on the day for which they are assigned. If you do not do the readings, you will get little out of the class. If you do the readings, but have nothing to say about them, then the class as a whole will suffer. The more you get involved, the more you will get out of the class, and the more exciting, engaging, and successful the class will be as whole. Ideally, students in this course: • Will gain a basic knowledge of the major forces and events shaping US expansion from 1776-1910s 4 • Will deepen their understandings of the course themes through critical analysis of the different phases of US expansion and the different peoples and places conquered or occupied by the US. • Will develop their skills of written and oral expression • Will gain experience doing historical research and in reading and interpreting primary and secondary sources • Will draw connections among the political, economic, cultural, and social dimensions of expansionism Course Requirements 1. Participation, Attendance and short papers. This category includes reading, attendance & participation in discussions. Students can participate in class by making points and connections, raising questions, listening and responding to the comments of other students, and otherwise engaging with the flow of the discussion. Informal writing assignments, which will not be given a letter grade but will be assigned a number from 0-4 that assesses their general quality, include 5 1-2-page Discussion Papers and 2 historical news reports (which will be explained in class). You may skip one of those 7 assignments, at your choosing (i.e. one of the discussion papers or one of the historical news reports). A variety of other short assignments for class preparation may also be required. Active listening and asking questions and making comments are integral parts of class participation. Regular attendance is expected (more than three unexcused absences will begin to severely impact your participation grade, and further absences will eventually lead to a withdrawal from class). (25%) 2. A short (@10 minute) in-class presentation, on a topic related to US Expansion and Empire Building, to be selected by the student. Ideas for topic include a president of your own choosing and his policies related to imperial expansion; a particular Indian Nation and how it confronted US expansion or how it built its own empire (e.g. Comanche or Sioux); an aspect of one of the US Wars in the period; the views of particular anti- or pro-imperialist Americans or non-American viewers of America; how some nation confronted US imperialism or invasion; or some other topic in US history that relates to empire building. Topics should fit somewhere within the central chronological range of the course, from 1776-1919 (though I am willing to consider topics 5 outside of these parameters; just talk with me). Guidelines for the presentation will be distributed, and students should select a topic by the end of the second week of classes. (5%) 3. An interpretive essay: a 5-6 page paper due in Week 7; guidelines will be distributed in class. (22%) 4. A second interpretive essay, due in Week 12. (22%) 5. Final Project: research essay. A 7-10 page paper on a topic relevant to the course, making use of both primary and secondary sources. A prospectus for your final project is due in week 13 and the final project is due Wednesday of Finals Week. Guidelines will be distributed in class after week 9. (26%) Note on Quiz Possibilities: depending on the quality of class discussions and the collective sense of how thoroughly and completely the reading is being done, we may need to add quizzes or other assignments to the course itinerary (in which case, the percentage weight of some of the above categories will be reduced to make room for the quizzes, etc). Grading Policies The work in all of the above categories will be taken into account to determine your final grade. In general, the writing asks you to go far beyond the recitation of facts and information. You will be formulating your own ideas and arguments, gathering and organizing evidence to support your positions, and putting it all together in finished essays that are at their best polished, engaging, original, creative, and/or provocative. I will distribute more specific criteria that I use in evaluating your longer papers. The Discussion Papers are more informal in orientation, and one of their purposes is to allow you to pursue your ideas and hone your writing talents without the pressure of grades. The following statements will give you some idea what level of work and participation constitutes what kind of grade in this course: Work that is of D-level or below does not rise to the standards of expectations in the class, which are reflected in the description of C-level work. C-level work is considered both average and respectable in this course. Work that merits a C represents a serious engagement with the class and the 6 course materials by the student. For papers, this means that the paper deals with its topic, makes use of the proper number and type of sources, shows that the student has grappled with the readings and issues, and advances a central idea or thesis. Yet, the thesis may be vague and there may be problems with the mechanics, organization or clarity of the paper. In terms of participation, the C-level student regularly attends, is attentive to what is going on in the classroom, occasionally offers ideas and perspectives in class, completes the Prep Papers in satisfactory fashion, and willingly contributes to small group discussions. B-level work is very good. It represents both serious engagement with and reasonable mastery of the course material. The B-level student maintains their degree of engagement throughout the course, and usually their work shows improvement. Papers that merit a B are well-crafted and organized, advance a central thesis that addresses the paper’s topic in an interesting or illuminating fashion, are mostly free from mechanical and grammatical errors, draw effectively on a range of materials, and are generally persuasive and cogent in their argument. B-level participation involves regular attendance and participation in class discussions. Comments and contributions are often based on a careful consideration of the readings. For example, such a student may sometimes point to a specific passage in the text to back up or develop their comment or question. A-level work is exceptional. Not only do A-level papers display all of the good qualities of a B-paper, their central argument is advanced with an exceptionally impressive degree of sophistication, originality or insight. The paper’s organization, craft and use of evidence are all excellent. In terms of participation, contributions to class discussions are both frequent and particularly insightful. Late Policy: Assignments that are up to 24 hours late will receive a 1/3 grade reduction (e.g. a B would become a B-); assignments turned in more than one but less than two days late will be lowered 2/3 of a grade; work turned in three days late will be lowered a full grade; work turned in beyond three-days late will be lowered a 1 and 1/3rd grade. Academic Honesty 7 Faith in your academic integrity is vital to all we do at UPS. It should go without saying that the college expects that all work submitted for evaluation in courses will be the product of the student’s own labor and imagination. Of course, you are free to speak with others about your work and share ideas and perspectives. In writing your papers, though, you are developing your own ideas and arguments. You can incorporate the ideas or words of others in your own paper, but to do so you must properly cite your sources. Turning in a paper that attempts to pass off the words or ideas of others as your own constitutes plagiarism (see The Logger for more information). Like other forms of cheating, plagiarism is a contamination that pollutes our environment. Students who knowingly turn in work that involves plagiarism or is marred by other forms of cheating will not pass the course, though more severe penalties may be recommended for egregious cases. One can understand the temptation to turn in illegitimate work: students working under intense pressures may turn to cheating as an easy way out. But to do so, you not only steal the work of others, you cheat yourself and your fellow students as well. A real degree from UPS cannot be obtained through looting. If you are worried about your grade or completing an assignment, please come and talk to me. I can work with you to help you get over the hurdles and make it possible for you to get something positive out of the course. Discussion Papers The class is divided into 5 “groups”—A, B. C, D & E. (This is basically for the purpose of dividing up the class—you will be writing your discussion papers individually, not in groups). Discussion Papers for your group are due on the days indicated in the course schedule with your group's letter in brackets next to the date (see below). Under no circumstances, including computer failure, may Discussion Papers be turned in late, since their purpose is to be available for use in the class discussion on the day on which they are due. (In certain circumstances, I may allow you to switch the day for which you write a discussion paper, but you must ask me about this at least 24-hours in advance). Discussion Papers should be typed and between 1 and 2 pages long. The Discussion Papers involve two components: a topic discussion and an issue identification: 8 Topic Discussion: For the topic discussion, I would like you to write 2-3 paragraphs or so about some aspect of the reading for that day that grabs your attention and you would like to discuss. I am not looking for you to summarize the reading. Instead, I would like you to identify some theme or issue raised in the reading and interpret its significance. You need not deal with the reading as a whole; in fact, you may want to focus on a small part of the larger reading. You may wish to draw comparisons between the readings of the day, or between the reading of the day and previous readings. You may wish to discuss how the reading relates to some larger issue in the class. You must include at least one quotation from the reading in your paper (normally, stronger papers use such citations). Please provide the page number in a footnote or in parentheses for your quotations. I will on occasion ask you to summarize or read your topic discussion for the class. Issue ID: The second component of the Discussion Paper is the identification of some issue that can be suitable for class discussion. This can be one or two sentences long, and it can be as simple as identifying a quote from one of the readings that you find illuminating and interesting or questionable and briefly stating what important issue you see in the quote. You might also raise a point of comparison between readings. The issue may be related to your topic discussion, though it need not be. Be prepared with these: I will on occasion ask you to present your issue id in class as a way to start discussion. Course Schedule Note: Readings with a number are from the History 368 Reader, the photocopied packet of readings; bulleted readings are from the books. Groups that have a discussion paper due on the readings for that day are noted in the brackets after the date. Part I: Genesis of Empire? Expansionism from the City on a Hill to the Declaration of Independence and the New Nation Week 1 (week of August 30-) 1.1 Introduction: Stars and Stripes over time 1.2 [Groups A and B]: 1. Charles Maier, excerpt from Among Empires 2. Niall Ferguson, excerpt from Colossus 9 • Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, ch 1. Explaining American Foreign Relations * / William Appleman Williams, The Open Door Policy: Economic Expansion and the Remaking of Societies/ Andrew Rotter, Gender, Expansionism, and Imperialism / Mary A. Renda, Paternalism and Imperial Culture Week 2 (Sept. 6-) 2.1 [Group C] • Nugent, Habits of Empire, foreword + ch. 1 • Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, ch 2 . The Origins of American Foreign Policy in the Revolutionary Era [* Documents /1. Governor John Winthrop Envisions a City Upon a Hill, 1630 / 4. The Declaration of Independence, 1776. 7. President George Washington Cautions Against Factionalism and Permanent Alliances in His Farewell Address, 1796 • Major Problems, ch. 1: Bradford Perkins, "The Unique American Prism" (p. 27) 2.2 [Group D] • Nugent, ch. 2 • Major Problems, ch. 4. The Louisiana Purchase [ * Documents 1. President Thomas Jefferson Assesses the French Threat in New Orleans, 1802 / 2. Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of France, Explains the Need to Sell Louisiana to the United States, 1803 / 3. Robert R. Livingston, American Minister to France, Recounts the Paris Negotiations, 1803 / 4. Federalist Alexander Hamilton Debunks Jefferson's Diplomacy, 1803 / 5. Jefferson Instructs Captain Meriwether Lewis on Exploration, 1803 /* Essays / Joyce Appleby, Jefferson's Resolute Leadership and Drive Toward Empire Week 3 (Sep. 13-) 3.1 [Group E] • Nugent, ch. 3 • Major Problems, from ch. 5 [5. Shawnee Chief Tecumseh Condemns US Land Grabs and Plays the British Card; 8. Former President Thomas Jefferson Predicts the Easy Conquest of Canada, 1812 • Major Problems, ch. 6 The Monroe Doctrine [ * Documents / 1. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams Warns Against the Search for "Monsters to Destroy," 1821/ 5. The Monroe Doctrine Declares the Western Hemisphere Closed to European Intervention, 1823 / 6. Colombia Requests an Explanation 10 of U.S. Intentions, 1824 / 7. Juan Bautista Alberdi of Argentina Warns Against the Threat of "Monroism" to the Independence of Spanish America, n.d./ * Essays //William E. Weeks, The Age of Manifest Destiny Begins Part II: United States Colonialism in Indian Country 3.2 Film: We Shall Remain: Tecumseh’s Vision Week 4 (Sept. 20-) 4.1 [Groups A and B (note, group A please write in connection to Lepore and Group B please tie into any of the other readings] 3. Jill Lepore, "Remembering American Frontiers" Consult website on Indian Removal and on William Apess on the revolt at Mashpee: http://www.teachushistory.org/indian-removal/resources •Nugent, 222-230 • Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, ch. 7, * Essays/ Theda Perdue, The Origins of Removal and the Fate of the Southeastern Indians // Robert V. Remini, Jackson's Good Intentions and the Inevitability of the Indian Removal Act 4.2 [Group C; Historical News Reports, Group E] • VanDevelder, Savages and Scoundrels, xi-19; 26-27; 44-68 • Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, ch. 7, documents: / documents: [Westward Expansion and Indian Removal // * Documents/ 1. Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen Protests Removal, 1830/ 2. The Indian Removal Act Authorizes Transfer of Eastern Tribes to the West, 1830/ 3. The Cherokee Nation Protests the Removal Policy, 1830 /4. President Andrew Jackson Defends Removal, 1830/ 5. Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia: The Supreme Court Refuses Jurisdiction over Indian Affairs, 1831/ 6. Cherokee Chief John Ross Denounces U.S. Removal Policy, 1836 / Week 5 (Sept. 27-) 5.1 [Group D] • VanDevelder, Savages and Scoundrels, chs. 3-4, 4. Chief Joseph, "An Indian's View of Indian Affairs" 5.2 [Group E; Historical News Reports, Group B] • VanDevelder, Savages and Scoundrels, chs. 5-6, appendix. “Treaty of Fort Laramie” 11 Part III: The Mexican War and Manifest Destiny Week 6 (Oct. 4-) 6.1 [Group A] • Nugent, chs. 5 and 7. • Major Problems: ch. 8. Manifest Destiny, Texas, and the War with Mexico [*Documents /1. Commander Sam Houston's Battle Cry for Texan Independence from Mexico, 1835/ 2. General Antonio López de Santa Anna Defends Mexican Sovereignty over Texas, 1837. 3/. Democratic Publicist John L. O'Sullivan Proclaims America's Manifest Destiny, 1839/ 6.2 [Group B; Historical News Reports, Group D] The Mexican War • Major Problems: ch. 8. Manifest Destiny, Texas, and the War with Mexico [*Documents 4. President James K. Polk Lays Claim to Texas and Oregon, 1845/ 5. Polk Asks Congress to Declare War on Mexico, 1846/ 6. The Wilmot Proviso Raises the Issue of Slavery in New Territories, 1846/ 7. Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster Protests the War with Mexico and the Admission of New States to the Union, 1848/ 8. Mexican Patriots Condemn U.S. Aggression, 1850 // * Essays/ Anders Stephanson, The Ideology and Spirit of Manifest Destiny //Thomas R. Hietala, Empire by Design, Not Destiny// David M. Pletcher, Polk's Aggressive Leadership [Friday 3.30: History Department Forum and Introduction (optional)] Week 7 (Oct. 11-) 7.1 [Group C; Historical News Reports, Group A] • Nugent, ch. 6, 230-36. 5. Michael Adas, "Machines and Manifest Destiny," excerpt from Dominance by Design: Technological Imperatives and America's Civilizing Mission 7.2 No Class; I am away at the Western History Association Conference <<Paper Due Friday by 4pm; Please turn papers in to the folder next to my office door, Wyatt 138] 12 Week 8 (Oct 18-) 8.1 fall break Part IV: Into the Pacific: China, Japan and the Case of Hawai'i 8.2 [Group D] • Nugent, ch. 9 8. Documents and Essays on Colonization, Pacific Markets, and Asian Labor Migration: Please read documents 1, 2, and 3. Week 9 (Oct. 25-) 9.1 [Group E; Historical News Reports, Group B] • Major Problems, ch. 9. Expansion to the Pacific and Asia [ * Documents 1. S. Wells Williams Remembers Protestant Missionary Work in China, 1883 / 2. American Merchants in Canton Plead for Protection During the Opium Crisis, 1839 / 3. A Chinese Official Recommends Pitting American Barbarians Against British Barbarians, 1841 / 4. Secretary of State Daniel Webster Instructs Caleb Cushing on Negotiating with China, 1843 / 5. Webster Warns European Powers Away from Hawai'i, 1851 / 6. Instructions to Commodore Matthew C. Perry for His Expedition to Japan, 1852 / 7. Ii Naosuke, Feudal Lord of Hikone, Advocates Accommodation with the United States, 1853 / 8. Tokugawa Nariaki, Feudal Lord of Mito, Argues Against Peace, 1853 //* Essays / Walter LaFeber, The Origins of the U.S.-Japanese Clash / Paul W. Harris, Protestant Missionaries and Cultural Imperialism in China 9.2 [Group A] 6. Amy Greenberg, "Manifest Destiny and Manly Missionaries: Expansionism in the Pacific" • Noenoe Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism, pp. 30-43 7. Richard Tucker, "Lords of the Pacific: Sugar barons in the Hawaiian and Philippine Islands" 13 8. Documents and Essays on Colonization, Pacific Markets, and Asian Labor Migration: read documents 4, "Hawaiians Petition" and 5, "A Foreigner Speculates on Hawaiian Land Acquisition" and the essay by Ronald Takaki, "Native and Asian Labor in the Colonization of Hawai'i" Race and Pedagogy National Conference, October 28-30 Week 10 (Nov. 1-) 10.1 [Group B; Historical News Reports Groups C] • Noenoe Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism, introduction, chs. 2 and 3 10.2 [Group C] 9. Eric Love, excerpt from Race Over Empire • Noenoe Silva, Aloha Betrayed, ch. 4 10. Excerpt from the Blount Report: Message from President Cleveland Week 11 (Nov. 8-) 11.1 • Major Problems, ch. 11, document 6. Queen Lili'uokalani Protests U.S. Intervention in Hawai'i, 1893, 1897 11.2 [Group D] • Silva, Aloha Betrayed, ch. 5. 11. Huanani-Kay Trask, excerpts from From a Native Daughter. Part V: Race, Economics, Immigration and the Domestic Culture of Empire, 1870s-1910s Week 12 (Nov. 15-) 12.1 : Crucible of Empire <Paper Due in Class> 12.2 [Group E; Historical News Reports Groups B] • Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues:, 3-38, 49-97 14 • Major Problems, ch 11: 1. Future Secretary of State William H. Seward Dreams of Hemispheric Empire, 1860 / 4. Captain Alfred T. Mahan Advocates a Naval Buildup, 1890 • Major Problems, ch. 12, document 7: McKinley Preaches his Imperial Gospel Week 13 (Nov. 22-) 13.1 [Group A: Historical News Reports Groups C and D] • Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues:, 105-121, 127-172 • Major Problems, ch 11: 5. Designers Rave About a Gentleman's GloballyInspired Décor, 1892; essay by Kristin Hoganson, "Cosmopolitan Domesticity" <Prospectus Due Tuesday by 5pm: Please turn them in to the folder next to my office door, Wyatt 138> 13.2 Thanksgiving Part VI: The Spanish-American War and the “Open Door”: The Philippines, China and the Renewal of Manifest Destiny in the New Century Week 14 (Nov. 29-) 14.1 [Group B; Historical News Reports Group E] 12. Kristin Hoganson, excerpt from Fighting for American Manhood 13. Theodore Roosevelt, "The Strenuous Life" 15. Documents on the debate over the Philippines 16. "Aguinaldo's Case" 17. Mark Twain, "To the Person Sitting in Darkness" 22. Theodore Roosevelt on Philippine Colonization Recommended: • Major Problems, ch. 14: Emily Rosenberg, "Tr's Civilizing Message: Race, Gender, and Dollar Diplomacy"/ and 14. (in reader) Michael Adas, “Improving on the Civilizing Mission” 14.2 [Group C; Historical News Reports Group A] 15 • Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 190-201 • Major Problems, ch. 13. The Open Door Policy and China [* Documents /1. The First Open Door Note Calls for Equal Trade Opportunity in China, 1899 / 2. The British Communicate a Friendly but Noncommittal Reply, 1899 / 3. The Russians Provide a Friendly but Noncommittal Reply, 1899 / 4. The Second Open Door Note Calls for Preservation of Chinese Independence, 1900 / 5. Missionary Evelyn Sites Describes the Emotional Conversion of a Chinese Woman, n.d. / 6. Missionary Anna Hartwell Discusses "Soul Winning," 1919 / 7. The Boxers Lash Out at Christian Missionaries and Converts, 1900 / * Essays / Michael H. Hunt, The Open Door Constituency's Pressure for U.S. Activism / Arnold Xiangze Jiang, U.S. Economic Expansion and the Defense of Imperialism at China's Expense / Jane Hunter, Women Missionaries and Cultural Conquest Week 15 (Dec. 6-) 15.1 (5/5) [Groups D and E] • Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues:, 175-177, 221-265 19. Rudyard Kipling, "The White Man's Burden" 20. "The White Man's Duty" in The American Missionary 21. Thomas Fortune, "The White Man's Burden," in New York Age • Major Problems, ch. 12; Document 6: American Anti-Imperialist League Platform • Nugent, Postscript 16 other definitions of “Imperialism” (a selection, from LatinLibrary.com) Imperialism may be defined as the effective domination by a relatively strong state over a weaker people whom it does not control as it does its home population, or as the effort to secure such domination. . . . [On] a political level, imperialism may be said to exist when a weaker people cannot act with respect to what it regards as fundamental domestic or foreign concerns for fear of foreign reprisals that it believes itself unable to counter. . . . When imperialism manifests itself directly its presence is unambiguous enough: A political authority emanating from a foreign land sets itself up as locally sovereign, claiming the final right to determine and enforce the law over a people recognized as distinct from that of the imperial homeland. Tony Smith, The Pattern of Imperialism: the United States, Great Britain, and the LateIndustrializing World Since 1815 (Cambridge University Press, 1981). Empire, then, is a relationship, formal or informal, in which one state controls the effective political sovereignty of another political society. It can be achieved by force, by political collaboration, by economic, social, or cultural dependence. Imperialism is simply the process or policy of establishing or maintaining an empire. Michael W. Doyle, Empires (Cornell 1986) p. 45. [Imperialism is] something more general than just direct colonial rule; it will encompass informal domination as well, including relations of domination within the industrially advanced world. At the same time, it will mean something more specific than mere inequality of power between different nations and the effects of that inequality. Effective control will remain an essential quality for the notion of imperialism. Schwabe, Klaus. "The Global Role of the United States and its Imperial Consequences, 1898-1973." Imperialism and After: Continuities and Discontinuities. Eds. Wolfgang Mommsen and Jurgen Osterhammel (London 1986). I define 'Imperialism' as a system devised by elites to keep the poor and powerless poor and powerless. Imperialism is a system which will mutate as often as required by changing circumstances to make sure the poor and powerless remain poor and powerless. To do so, the elites of imperialism use all means to undermine, bypass or destroy any counter-systems which have been invented by the poor and powerless to give themselves more power. Jim Wingate, Saviour of Linguistic Imperialism? A Counterblast to Corpus Linguistics (Plymouth 2000). 17 "Men with guns looking for money". David Cooper (2006). 18