MIDTERM REVIEW Lectures 1-15

advertisement

MIDTERM REVIEW

Lectures 1-15

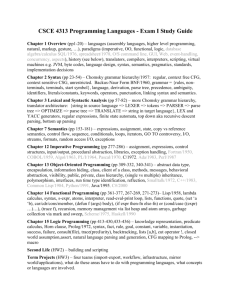

LECTURE 1: OVERVIEW AND HISTORY

•Evolution

• Design considerations: What is a good or bad programming construct?

• Early 70s: structured programming in which goto-based control flow was replaced by high-level

constructs (e.g. while loops and case statements).

• Late 80s: nested block structure gave way to object-oriented structures.

•Special Purposes

• Many languages were designed for a specific problem domain (e.g Scientific applications, Business

applications, Artificial intelligence, Systems programming, Internet programming, etc).

•Personal Preference

• The strength and variety of personal preference makes it unlikely that anyone will ever develop a

universally accepted programming language.

LECTURE 1: OVERVIEW AND HISTORY

•Expressive Power

• Theoretically, all languages are equally powerful (Turing complete).

• Language features have a huge impact on the programmer's ability to read, write, maintain, and analyze programs.

•Ease of Use for Novice

• Low learning curve and often interpreted, e.g. Basic and Logo.

•Ease of Implementation

• Runs on virtually everything, e.g. Basic, Pascal, and Java.

•Open Source

• Freely available, e.g. Java.

•Excellent Compilers and Tools

• Supporting tools to help the programmer manage very large projects.

•Economics, Patronage, and Inertia

• Powerful sponsor: Cobol, PL/I, Ada.

• Some languages remain widely used long after "better" alternatives.

LECTURE 1: OVERVIEW AND HISTORY

Classification of Programming Languages

• Declarative: Implicit solution. What should the computer do?

• Functional

•

Lisp, Scheme, ML, Haskell

• Logic

•

Prolog

• Dataflow

•

Simulink, Scala

• Imperative: Explicit solution. How should the computer do it?

• Procedural

•

Fortran, C

• Object-Oriented

•

Smalltalk, C++, Java

LECTURE 2: COMPILATION AND INTERPRETATION

Programs written in high-level languages can be run in two ways.

• Compiled into an executable program written in machine language for the target

machine.

• Directly interpreted and the execution is simulated by the interpreter.

In general, which approach is more efficient?

LECTURE 2: COMPILATION AND INTERPRETATION

Programs written in high-level languages can be run in two ways.

• Compiled into an executable program written in machine language for the target

machine.

• Directly interpreted and the execution is simulated by the interpreter.

In general, which approach is more efficient?

Compilation is always more efficient…but interpretation leads to more flexibility.

LECTURE 2: COMPILATION AND INTERPRETATION

How do you choose? Typically, most languages are implemented using a mixture of

both approaches.

Practically speaking, there are two aspects that distinguish what we consider

“compilation” from “interpretation”.

• Thorough Analysis

• Compilation requires a thorough analysis of the code.

• Non-trivial Transformation

• Compilation generates intermediate representations that typically do not resemble the source code.

LECTURE 2: COMPILATION AND INTERPRETATION

Preceprocessing

• Initial translation step.

• Slightly modifies source code to be interpreted more efficiently.

• Removing comments and whitespace, grouping characters into tokens, etc.

Linking

• Linkers merge necessary library routines to create the final executable.

LECTURE 2: COMPILATION AND INTERPRETATION

Post-Compilation Assembly

• Many compilers translate the source code into assembly rather than machine

language.

• Changes in machine language won’t affect source code.

• Assembly is easier to read (for debugging purposes).

Source-to-source Translation

• Compiling source code into another high-level language.

• Early C++ programs were compiled into C, which was compiled into assembly.

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

Front-End Analysis

Source Program

Scanner

(Lexical Analysis)

Tokens

Parser

(Syntax Analysis)

Parse Tree

Semantic Analysis

& Intermediate Code Generation

Abstract Syntax Tree

Back-End Synthesis

Abstract Syntax Tree

Machine-Independent

Code Improvement

Modified Intermediate Form

Target Code Generation

Assembly or Object Code

Machine-Specific Code

Improvement

Modified Assembly or Object Code

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

Lexical analysis is the process of tokenizing characters that appear in a program.

A scanner (or lexer) groups characters together into meaningful tokens which are then

sent to the parser.

As the scanner reads in the characters, it produces meaningful tokens.

Tokens are typically defined using regular expressions, which are understood by a

lexical analyzer generator such as lex.

What the scanner picks up:

The resulting tokens:

‘i’, ‘n’, ‘t’, ‘ ’, ‘m’, ‘a’, ‘i’, ‘n’, ‘(’, ‘)’, ‘{’….

int, main, (, ), {, int, i, =, getint, (, ), ….

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

Syntax analysis is performed by a parser which takes the tokens generated by the

scanner and creates a parse tree which shows how tokens fit together within a valid

program.

The structure of the parse tree is dictated by the grammar of the programming

language.

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

Semantic analysis is the process of attempting to discover whether a valid pattern of

tokens is actually meaningful.

Even if we know that the sequence of tokens is valid, it may still be an incorrect

program.

For example:

a = b;

What if a is an int and b is a character array?

To protect against these kinds of errors, the semantic analyzer will keep track of the

types of identifiers and expressions in order to ensure they are used consistently.

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

What kinds of errors can be caught in the lexical analysis phase?

• Invalid tokens.

What kinds of errors are caught in the syntax analysis phase?

• Syntax errors: invalid sequences of tokens.

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

• Static Semantic Checks: semantic rules that can be checked at compile time.

•

•

•

•

Type checking.

Every variable is declared before used.

Identifiers are used in appropriate contexts.

Checking function call arguments.

• Dynamic Semantic Checks: semantic rules that are checked at run time.

Array subscript values are within bounds.

Arithmetic errors, e.g. division by zero.

Pointers are not dereferenced unless pointing to valid object.

When a check fails at run time, an exception is raised.

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

• Assuming C++, what kinds of errors are these?

• int = @3;

• int = ?3;

• int y = 3; x = y;

• “Hello, World!

• int x; double y = 2.5; x = y;

• void sum(int, int); sum(1,2,3);

• myint++

• z = y/x // y is 1, x is 0

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

• Assuming C++, what kinds of errors are these?

• int = @3;

// Lexical

• int = ?3;

// Syntax

• int y = 3; x = y;

// Static semantic

• “Hello, World!

// Syntax

• int x; double y = 2.5; x = y;

// Static semantic

• void sum(int, int); sum(1,2,3);

// Static Semantic

• myint++

// Syntax

• z = y/x // y is 1, x is 0

// Dynamic Semantic

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

Code Optimization

• Once the AST (or alternative intermediate form) has been generated, the compiler

can perform machine-independent code optimization.

• The goal is to modify the code so that it is quicker and uses resources more

efficiently.

• There is an additional optimization step performed after the creation of the object

code.

LECTURE 3: COMPILER PHASES

Target Code Generation

• Goal: translate the intermediate form of the code (typically, the AST) into object

code.

• In the case of languages that translate into assembly language, the code generator

will first pass through the symbol table, creating space for the variables.

• Next, the code generator passes through the intermediate code form, generating the

appropriate assembly code.

• As stated before, the compiler makes one more pass through the object code to

perform further optimization.

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

We know from the previous lecture that the front-end of the compiler has three main phases:

• Scanning

• Parsing

Syntax Verification

• Semantic Analysis

Scanning

• Identifies the valid tokens, the basic building blocks, within a program.

Parsing

• Identifies the valid patterns of tokens, or constructs.

So how do we specify what a valid token is? Or what constitutes a valid construct?

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

Tokens can be constructed from regular characters using just three rules:

1. Concatenation.

2. Alternation (choice among a finite set of alternatives).

3. Kleene Closure (arbitrary repetition).

Any set of strings that can be defined by these three rules is a regular set.

Regular sets are generated by regular expressions.

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

Formally, all of the following are valid regular expressions (let R and S be regular

expressions and let Σ be a finite set of symbols):

• The empty set.

• The set containing the empty string 𝜖.

• The set containing a single literal character 𝛼 from the alphabet Σ.

• Concatenation: RS is the set of strings obtained by concatenation of one string from

R with a string from S.

• Alternation: R|S describes the union of R and S.

• Kleene Closure: R* is the set of strings that can be obtained by concatenating any

number of strings from R.

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

You can either use parentheses to avoid ambiguity or assume Kleene star has the

highest priority, followed by concatenation then alternation.

Examples:

• a* = {𝜖, a, aa, aaa, aaaa, aaaaa, …}

• a | b* = {𝜖, a, b, bb, bbb, bbbb, …}

• (ab)* = {𝜖, ab, abab, ababab, abababab, …}

• (a|b)* = {𝜖, a, b, aa, ab, ba, bb, aaa, aab, …}

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

Create regular expressions for the following examples:

• Zero or more c’s followed by a single a or a single b.

• Binary strings starting and ending with 1.

• Binary strings containing at least 3 1’s.

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

Create regular expressions for the following examples:

• Zero or more c’s followed by a single a or a single b.

c*(a|b)

• Binary strings starting and ending with 1.

1|1(0|1)*1

• Binary strings containing at least 3 1’s.

0*10*10*1(0|1)*

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

We can completely define our tokens in terms of regular expressions, but more

complicated constructs necessitate recursion.

The set of strings that can be defined by adding recursion to regular expressions is

known as a Context-Free Language.

Context-Free Languages are generated by Context-Free Grammars.

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

Context-free grammars are composed of rules known as productions.

Each production has left-hand side symbols known as non-terminals, or variables.

On the right-hand side, a production may contain terminals (tokens) or other nonterminals.

One of the non-terminals is named the start symbol.

expr id | number | - expr | ( expr ) | expr op expr

op + | - | * | /

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

So, how do we use the context-free grammar to generate syntactically valid strings of

terminals (or tokens)?

1. Begin with the start symbol.

2. Choose a production with the start symbol on the left side.

3. Replace the start symbol with the right side of the chosen production.

4. Choose a non-terminal A in the resulting string.

5. Replace A with the right side of a production whose left side is A.

6. Repeat 4 and 5 until no non-terminals remain.

LECTURE 7: PARSING

program expr

expr term expr_tail

expr_tail + term expr_tail | 𝜖

term factor term_tail

term_tail * factor term_tail | ϵ

factor (expr) | int

How can we derive the following strings from this grammar?

• (3 + 1)

• 3+2*5

• (1 + 5) * 7

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

Write a grammar which recognizes if-statements of the form:

if expression

statements

else

statements

where expressions are of the form id > num or id < num.

Statements can be any numbers of statements of the form id = num or print id.

LECTURE 4: SYNTAX

program if expr stmts else stmts

expr id > num | id < num

stmts stmt stmts | stmt

stmt id = num | print id

LECTURE 5: SCANNING

A recognizer for a language is a program that takes a string x as input and

answers “yes” if x is a sentence of the language and “no” otherwise.

In the context of lexical analysis, given a string and a regular expression, a recognizer of

the language specified by the regular expression answers “yes” if the string is in the

language.

How can we recognize a regular expression (int) ? What about (int | for)?

We could, for example, write an ad hoc scanner that contained simple conditions to test,

the ability to peek ahead at the next token, and loops for numerous characters of the

same type.

LECTURE 5: SCANNING

A set of regular expressions can be compiled into a recognizer automatically by

constructing a finite automaton using scanner generator tools (lex, for example).

A finite automaton is a simple idealized machine that is used to recognize patterns within some input.

• A finite automaton will accept or reject an input depending on whether the pattern defined by

the finite automaton occurs in the input.

The elements of a finite automaton, given a set of input characters, are

• A finite set of states (or nodes).

• A specially-denoted start state.

• A set of final (accepting) states.

• A set of labeled transitions (or arcs) from one state to another.

LECTURE 5: SCANNING

Finite automata come in two flavors.

• Deterministic

• Never any ambiguity.

• For any given state and any given input, only one possible transition.

• Non-deterministic

• There may be more than one transition from any given state for any given character.

• There may be epsilon transitions – transitions labeled by the empty string.

There is no obvious algorithm for converting regular expressions to DFAs.

LECTURE 5: SCANNING

Typically scanner generators create DFAs from regular expressions in the following

way:

• Create NFA equivalent to regular expression.

• Construct DFA equivalent to NFA.

• Minimize the number of states in the DFA.

LECTURE 5: SCANNING

• Concatenation: ab

b

a

s

𝜖

f

a

𝜖

s

• Alternation: a|b

f

𝜖

𝜖

b

𝜖

• Kleene Closure: a*

s

a

𝜖

𝜖

𝜖

f

LECTURE 5: SCANNING

Create NFAs for the regular expressions we created before:

• Zero or more c’s followed by a single a or a single b.

c*(a|b)

• Binary strings starting and ending with 1.

1|1(0|1)*1

• Binary strings containing at least 3 1’s.

0*10*10*1(0|1)*

LECTURE 6: SCANNING PART 2

How do we take our minimized DFA and practically implement a scanner? After all,

finite automata are idealized machines. We didn’t actually build a physical

recognizer yet! Well, we have two options.

• Represent the DFA using goto and case (switch) statements.

• Handwritten scanners.

• Use a table to represent states and transitions. Driver program simply indexes table.

• Auto-generated scanners.

• The scanner generator Lex creates a table and driver in C.

• Some other scanner generators create only the table for use by a handwritten driver.

a

LECTURE 6: SCANNING PART 2

S1

state = s1

token = ‘’

loop

case state of

s1:

case in_char of

‘c’: state = s2

else error

s2:

case in_char of

‘a’: state = s1

‘b’: state = s1

‘ ’: state = s1

return token

else error

token = token + in_char

read new in_char

c

b

S2

LECTURE 6: SCANNING PART 2

Longest Possible Token Rule

So, why do we need to peek ahead? Why not just accept when we pick up ‘c’ or

‘cac’?

Scanners need to accept as many tokens as they can to form a valid token.

For example, 3.14159 should be one literal token, not two (e.g. 3.14 and 159).

So when we pick up ‘4’, we peek ahead at ‘1’ to see if we can keep going or return

the token as is. If we peeked ahead after ‘4’ and saw whitespace, we could return

the token in its current form.

A single peek means we have a look-ahead of one character.

a

LECTURE 6: SCANNING PART 2

S1

c

Table-driven scanning approach:

b

State

‘a’

‘b’

‘c’

Return

S1

-

-

S2

-

S2

S1

S1

-

token

A driver program uses the current state and input character to

index into the table. We can either

• Move to a new state.

• Return a token (and save the image).

• Raise an error (and recover gracefully).

S2

LECTURE 7: PARSING

So now that we know the ins-and-outs of how compilers determine the valid tokens of

a program, we can talk about how they determine valid patterns of tokens.

A parser is the part of the compiler which is responsible for serving as the recognizer

of the programming language, in the same way that the scanner is the recognizer for

the tokens.

LECTURE 7: PARSING

Even though we typically picture parsing as the stage that comes after scanning, this

isn’t really the case.

In a real scenario, the parser will generally call the scanner as needed to obtain input

tokens. It creates a parse tree out of the tokens and passes it to the later stages of

the compiler.

This style of compilation is known as syntax-directed translation.

LECTURE 7: PARSING

Let’s review context-free grammars. Each context-free grammar has four components:

• A finite set of tokens (terminal symbols)

• A finite set of nonterminals.

• A finite set of productions N (T | N)*

• A special nonterminal called the start symbol.

The idea is similar to regular expressions, except that we can create recursive

definitions. Therefore, context-free grammars are more expressive.

LECTURE 7: PARSING

Given a context-free grammar, parsing is the process of determining whether the

start symbol can derive the program.

• If successful, the program is a valid program.

• If failed, the program is invalid.

LECTURE 7: PARSING

There are two classes of grammars for which linear-time parsers can be constructed:

• LL – “Left-to-right, leftmost derivation”

• Input is read from left to right.

• Derivation is left-most.

• Can be hand-written or generated by a parser generator.

• LR – “Left-to-right, rightmost derivation”

•

•

•

•

Input is read from left to right.

Derivation is right-most.

More common, larger class of grammars.

Almost always automatically generated.

LECTURE 7: PARSING

• LL parsers are Top-Down (“Predictive”) parsers.

• Construct the parse tree from the root down, predicting the production used based on some

lookahead.

• LR parsers are Bottom-Up parsers.

• Construct the parse tree from the leaves up, joining nodes together under single parents.

LECTURE 8: PARSING

There are two types of LL parsers: Recursive Descent Parsers and Table-Driven TopDown Parsers.

Recursive descent parsers are an LL parser in which every non-terminal in the

grammar corresponds to a subroutine of the parser.

• Typically hand-written but can be automatically generated.

• Used when a language is relatively simple.

LECTURE 8: PARSING

In a table-driven parser, we have two elements:

• A driver program, which maintains a stack of symbols. (language independent)

• A parsing table, typically automatically generated. (language dependent)

LECTURE 8: PARSING

Here’s the general method for performing table-driven parsing:

• We have a stack of grammar symbols. Initially, we just push the start symbol.

• We have a string of input tokens, ending with $.

• We have a parsing table M[N, T].

• We can index into M using the current non-terminal at the top of the stack and the input token.

1. If top == input == ‘$’: accept.

2. If top == input: pop the top of the stack, read new input token, goto 1.

3. If top is nonterminal:

if M[N, T] is a production: pop top of stack and replace with production, goto 1.

else error.

4. Else error.

LECTURE 8: PARSING

Calculating an LL(1) parsing table includes calculating the first and follow sets. This is

how we make decisions about which production to take based on the input.

LECTURE 8: PARSING

First Sets

Case 1: Let’s say N 𝜔. To figure out which input tokens will allow us to replace N

with 𝜔, we calculate First(𝜔) – the set of tokens which could start the string 𝜔.

• If X is a terminal symbol, First(X) = X.

• If X is 𝜖, add 𝜖 to First(X).

• If X is a non-terminal, look at all productions where X is on left-hand side. Each

production will be of the form: X 𝑌1 𝑌2 …𝑌𝑘 where Y is a nonterminal or terminal.

Then:

•

•

•

•

•

Put First(𝑌1 ) - 𝜖 in First(X).

If 𝜖 is in First(𝑌1 ), then put First(𝑌2 ) - 𝜖 in First(X).

If 𝜖 is in First(𝑌2 ), then put First(𝑌3 ) - 𝜖 in First(X).

…

If 𝜖 is in 𝑌1 , 𝑌2 , …, 𝑌𝑘 , then add 𝜖 to First(X).

LECTURE 8: PARSING

If we compute First(X) for every terminal and non-terminal X in a grammar, then we

can compute First(𝜔), the tokens which can veritably start any string derived from 𝜔.

Why do we care about the First(𝜔) sets? During parsing, suppose the top-of-stack

symbol is nonterminal A and there are two productions A → α and A → β. Suppose

also that the current token is a. Well, if First(α) includes a, then we can predict this will

be the production taken.

LECTURE 8: PARSING

Follow Sets

Follow(𝑁) gives us the set of terminal symbols that could follow the non-terminal

symbol N. To calculate Follow(N), do the following:

• If N is the starting non-terminal, put EOF (or other program-ending symbol) in

Follow(N).

• If X 𝛼𝑁, where 𝛼 is some string of non-terminals and/or terminals, put Follow(X)

in Follow(N).

• If X 𝛼𝑁𝛽 where 𝛼, 𝛽 are some string of non-terminals and/or terminals, put

First(𝛽) in Follow(N). If First(𝛽) includes 𝜖, then put Follow(X) in Follow(N).

LECTURE 8: PARSING

Why do we care about the Follow(N) sets? During parsing, suppose the top-of-stack

symbol is nonterminal A and there are two productions A → α and A → β. Suppose

also that the current token is a. What if neither First(𝛼) nor First(𝛽) contain a, but they

contain 𝜖? We use the Follow sets to determine which production to take.

LECTURE 9: COMPUTING AN LL(1) PARSING TABLE

The basic outline for creating a parsing table from a LL(1) grammar is the following:

• Compute the First sets of the non-terminals.

• Compute the Follow sets of the non-terminals.

• For each production N 𝜔,

• Add N 𝜔 to M[ N, t] for each t in First(𝜔).

• If First(𝜔) contains 𝜖, add N 𝜔 to M[ N, t] for each t in Follow(N).

• All undefined entries represent a parsing error.

LECTURE 9: COMPUTING AN LL(1) PARSING TABLE

stmt if expr then stmt else stmt

stmt while expr do stmt

Let’s compute the LL(1) parsing table for this

grammar and parse the string:

stmt begin stmts end

while id do begin begin end ; end $

stmts stmt ; stmts

stmts ε

expr id

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

We’ve discussed in previous lectures how the syntax analysis phase of compilation

results in the creation of a parse tree.

Semantic analysis is performed by annotating, or decorating, the parse tree.

These annotations are known as attributes.

An attribute grammar “connects” syntax with semantics.

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Attribute Grammars

• Each grammar production has a semantic rule with actions (e.g. assignments) to

modify values of attributes of (non)terminals.

• A (non)terminal may have any number of attributes.

• Attributes have values that hold information related to the (non)terminal.

• General form:

production

<A> <B> <C>

semantic rule

A.a := ...; B.a := ...; C.a := ...

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Some points to remember:

• A (non)terminal may have any number of attributes.

• The val attribute of a (non)terminal holds the subtotal value of the subexpression.

• Nonterminals are indexed in the attribute grammar to distinguish multiple

occurrences of the nonterminal in a production – this has no bearing on the grammar

itself.

• Strictly speaking, attribute grammars only contain copy rules and semantic functions.

• Semantic functions may only refer to attributes in the current production.

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Strictly speaking, attribute grammars only consist of copy rules and calls to semantic

functions. But in practice, we can specify well-defined notation to make the semantic

rules look more code-like.

E1 E2 + T

E1 E2 – T

E T

T1 T2 * F

T1 T2 / F

TF

F1 - F2

F(E)

F const

E1 . val ≔ E2 . val + T. val

E1 . val ≔ E2 . val − T. val

E. val ∶= T. val

T1 . val ≔ T2 . val ∗ F. val

T1 . val ≔ T2 . val/F. val

T. val ∶= F. val

F1 . val ≔ −F2 . val

F. val ∶= E. val

F. val ∶= const. val

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Evaluation of the attributes

is called the decoration of

the parse tree. Imagine we

have the string (1+3)*2. The

parse tree is shown here.

The val attribute of each

symbol is shown beside it.

Attribute flow is upward in

this case.

The val of the overall

expression is the val of the

root.

(

E

1

T

1

F

1

const 1

T

4

F

4

E

4

+

E

8

T

8

*

F

2

const 2

)

T

3

F

3

const 3

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Each grammar production A 𝜔 is associated with a set of semantic rules of the

form

b := f(c1, c2, …, ck)

• If b is an attribute associated with A, it is called a synthesized attribute.

• If b is an attribute associated with a grammar symbol on the right side of the

production (that is, in 𝜔) then b is called an inherited attribute.

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Synthesized attributes of a node hold values that are computed from attribute values

of the child nodes in the parse tree and therefore information flows upwards.

production

E1 E2 + T

semantic rule

E1.val := E2.val + T.val

E 4

E

1

+

T 3

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

Inherited attributes of child nodes are set by the parent node or sibling nodes and

therefore information flows downwards. Consider the following attribute grammar.

𝐷𝑇𝐿

𝑇 𝑖𝑛𝑡

𝑇 𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑙

𝐿 𝐿1 , 𝑖𝑑

𝐿 𝑖𝑑

real id1, id2, id3

𝐿. 𝑖𝑛 = 𝑇. 𝑡𝑦𝑝𝑒

𝑇. 𝑡𝑦𝑝𝑒 = 𝑖𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑔𝑒𝑟

𝑇. 𝑡𝑦𝑝𝑒 = 𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑙

𝐿1 . 𝑖𝑛 = 𝐿. 𝑖𝑛, 𝑎𝑑𝑑𝑡𝑦𝑝𝑒(𝑖𝑑. 𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑦, 𝐿. 𝑖𝑛)

𝑎𝑑𝑑𝑡𝑦𝑝𝑒(𝑖𝑑. 𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑦, 𝐿. 𝑖𝑛)

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

In the same way that a context-free grammar does not indicate how a string should

be parsed, an attribute grammar does not specify how the attribute rules should be

applied. It merely defines the set of valid decorated parse trees, not how they are

constructed.

An attribute flow algorithm propagates attribute values through the parse tree by

traversing the tree according to the set (write) and use (read) dependencies (an

attribute must be set before it is used).

LECTURE 10: SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

A grammar is called S-attributed if all attributes are synthesized.

A grammar is called L-attributed if the parse tree traversal to update attribute

values is always left-to-right and depth-first.

• For a production A X1 X2 X3 … Xn

• The attributes of 𝑋𝑗 (1<= j <= n) only depend on:

• The attributes of X1 X2 X3 … Xj−1 .

• The inherited attributes of A.

Values of inherited attributes must be passed down to children from left to right.

Semantic rules can be applied immediately during parsing and parse trees do not need

to be kept in memory. This is an essential grammar property for a one-pass compiler.

An S-attributed grammar is a special case of an L-attributed grammar.

NAMES

A name is a mnemonic character string used to represent something else.

• Typically alphanumeric characters (i.e. “myint”) but can also be other symbols (i.e. ‘+’).

• Names enable programmers to refer to variables, constants, operations, and types instead

of low level concepts such as memory address.

• Names are essential in high-level languages for supporting abstraction.

• In this context, abstraction refers to the ability to hide a program fragment behind a name.

• By hiding the details, we can use the name as a black box. We only need to consider the object’s purpose,

rather than its implementation.

NAMES

Names enable control abstractions and data abstractions in high level

languages.

• Control Abstraction

• Subroutines (procedures and functions) allow programmers to focus on a manageable subset

of program text, subroutine interface hides implementation details.

• Control flow constructs (if-then, while, for, return) hide low-level machine ops.

• Data Abstraction

• Object-oriented classes hide data representation details behind a set of operations.

BINDING

A binding is an association between a name and an entity. The binding time is the time at which a

binding is created, or in other words, when an implementation decision is made. There are many

different times when binding can occur:

• Language design time: the design of specific language constructs.

• Syntax (names grammar)

• if (a>0) b:=a; (C syntax style)

• Keywords (names builtins)

• class (C++ and Java), extern

• Reserved words (names special constructs)

• main (C)

• Meaning of operators (operator operation)

• + (add), % (mod), ** (power)

• Built-in primitive types (type name type)

• float, short, int, long, string

BINDING

• Language implementation time: fixation of implementation constants.

• Examples: precision of types, organization and maximum sizes of stack and heap, etc.

• Program writing time: the programmer's choice of algorithms and data structures.

• Examples: A function may be called sum_grades(), a variable may be called x.

• Compile time: the time of translation of high-level constructs to machine code and

choice of memory layout for data objects.

• Example: translate “for(i=0; i<100; i++) a[i] = 1.0;”?

• Link time: the time at which multiple object codes (machine code files) and libraries

are combined into one executable.

• Example: which cout routine to use? /usr/lib/libc.a or /usr/lib/libc.so?

BINDING

• Load time: when the operating system loads the executable in memory.

• Example: In an older OS, the binding between a global variable and the physical memory location is

determined at load time.

• Run time: when a program executes.

• Example: Binding between the value of a variable to the variable.

OBJECT LIFETIME

Key events in an object’s lifetime:

• Object creation.

• Creation of bindings.

• The object is manipulated via its binding.

• Deactivation and reactivation of (temporarily invisible) bindings. (in-and-out of scope)

• Destruction of bindings.

• Destruction of object.

The time between binding creation and binding destruction is the binding’s lifetime.

The time between object creation and object destruction is the object’s lifetime.

DANGLING REFERENCE

When the binding lifetime exceeds the object’s lifetime, we have a dangling

reference. Typically, this is a sign of a bug.

…

myobject = new SomeClass;

foo(myobject);

foo(SomeClass *a)

{

……

delete (myobject);

a->action();

}

// myobject is a global variable

MEMORY LEAKS

When all bindings are destroyed, but the object still exists, we have a memory leak.

{

SomeClass* myobject = new SomeClass;

...

...

myobject->action();

return;

}

STORAGE MANAGEMENT

Obviously, objects need to be stored somewhere during the execution of the

program. The lifetime of the object, however, generally decides the storage

mechanism used. We can divide them up into three categories.

• The objects that are alive throughout the execution of a program (e.g.

global variables).

• The objects that are alive within a routine (e.g. local variables).

• The objects whose lifetime can be dynamically changed (the objects that

are managed by the ‘new/delete’ constructs).

STORAGE MANAGEMENT

The three types of objects correspond to three principal storage allocation mechanisms.

• Static objects have an absolute storage address that is retained throughout the execution of

the program.

• Global variables and data.

• Subroutine code and class method code.

• Stack objects are allocated in last-in first-out order, usually in conjunction with subroutine calls

and returns.

• Actual arguments passed by value to a subroutine.

• Local variables of a subroutine.

• Heap objects may be allocated and deallocated at arbitrary times, but require an expensive

storage management algorithm.

• Dynamically allocated data in C++.

• Java class instances are always stored on the heap.

TYPICAL PROGRAM/DATA LAYOUT IN MEMORY

Higher Addr

Stack

• Program code is at the bottom of the

memory region (code section).

• The code section is protected from runtime modification by the OS.

Heap

• Static data objects are stored in the

static region.

• Stack grows downward.

Static Data

Code

Lower Addr

• Heap grows upward.

STATIC ALLOCATION

• Program code is statically allocated in most implementations of imperative

languages.

• Statically allocated variables are history sensitive.

• Global variables keep state during entire program lifetime

• Static local variables in C/C++ functions keep state across function invocations.

• Static data members are “shared” by objects and keep state during program lifetime.

• Advantage of statically allocated objects is the fast access due to absolute

addressing of the object.

• Can static allocation be used for local variables?

• No, statically allocated local variables have only one copy of each variable. Cannot deal with the

cases when multiple copies of a local variable are alive!

• When does this happen?

STACK ALLOCATION

Each instance of a subroutine that is active has a subroutine frame (sometimes called

activation record) on the run-time stack.

• Compiler generates subroutine calling sequence to setup frame, call the routine, and to destroy the

frame afterwards.

Subroutine frame layouts vary between languages, implementations, and machine

platforms.

TYPICAL STACK-ALLOCATED SUBROUTINE FRAME

Lower Addr

Temporary storage

(e.g. for expression

evaluation)

Local variables

Bookkeeping

(e.g. saved CPU

registers)

Return address

fp

Higher Addr

Subroutine arguments

and returns

• Most modern processors have two

registers: fp (frame pointer) and sp (stack

pointer) to support efficient execution of

subroutines in high level languages.

• A frame pointer (fp) points to the frame

of the currently active subroutine at run

time.

• Subroutine arguments, local variables,

and return values are accessed by

constant address offsets from the fp.

Typical subroutine frame layout

SUBROUTINE FRAMES ON THE STACK

sp

A

Subroutine frames are pushed and popped

onto/from the runtime stack.

• The stack pointer (sp) points to the next available

free space on the stack to push a new frame onto

when a subroutine is called.

• The frame pointer (fp) points to the frame of the

currently active subroutine, which is always the

topmost frame on the stack.

• The fp of the previous active frame is saved in the

current frame and restored after the call.

• In this example:

M called A

A called B

B called A

fp

B

A

M

temporaries

local variables

bookkeeping

return address

arguments

temporaries

local variables

bookkeeping

return address

arguments

temporaries

local variables

bookkeeping

return address

arguments

temporaries

local variables

bookkeeping

return address

arguments

HEAP ALLOCATION

The heap is used to store objects who lifetime is dynamic.

• Implicit heap allocation:

•

•

•

•

•

Done automatically.

Java class instances are placed on the heap.

Scripting languages and functional languages make extensive use of the heap for storing objects.

Some procedural languages allow array declarations with run-time dependent array size.

Resizable character strings.

• Explicit heap allocation:

• Statements and/or functions for allocation and deallocation.

• Malloc/free, new/delete.

HEAP ALLOCATION PROBLEMS

Heap is a large block of memory (say N bytes).

• Requests for memory of various sizes may arrive randomly.

• For example, a program executes ‘new’.

• Each request may ask for 1 to N bytes.

• If a request of X bytes is granted, a continuous X bytes in the heap is allocated for

the request. The memory will be used for a while and then returned to the system

(when the program executes ‘delete’).

The problem: how can we make sure memory is allocated such that as many requests

as possible are satisfied?

HEAP ALLOCATION EXAMPLE

Example: 10KB memory to be managed.

r1 = req(1K);

r2 = req (2K);

r3 = req(4k);

free(r2);

free(r1);

r4 = req(4k);

How we assign memory makes a difference!

• Internal fragment: unused memory within a block.

• Example: asking for 100 bytes and get a 512 bytes block.

• External fragment: unused memory between blocks.

• Even when the total available memory is more than a request, the request cannot be satisfied as in the

example.

GARBAGE COLLECTION

Explicit manual deallocation errors are among the most expensive and hard to detect

problems in real-world applications.

• If an object is deallocated too soon, a reference to the object becomes a dangling

reference.

• If an object is never deallocated, the program leaks memory.

Automatic garbage collection removes all objects from the heap that are not

accessible, i.e. are not referenced.

• Used in Lisp, Scheme, Prolog, Ada, Java, Haskell.

• Disadvantage is GC overhead, but GC algorithm efficiency has been improved.

• Not always suitable for real-time processing.

GARBAGE COLLECTION

How does it work roughly?

• The language defines the lifetime of objects.

• The runtime keeps track of the number of references (bindings) to each object.

• Increment when a new reference is made, decrement when the reference is destroyed.

• Can delete when the reference count is 0.

• Need to determine when a variable is alive or dead based on language

specification.

SCOPE

• Statically scoped language: the scope of bindings is determined at compile time.

• Used by almost all but a few programming languages.

• More intuitive than dynamic scoping.

• We can take a C program and know exactly which names refer to which objects at which points in the

program solely by looking at the code.

• Dynamically scoped language: the scope of bindings is determined at run time.

• Used in Lisp (early versions), APL, Snobol, and Perl (selectively).

• Bindings depend on the flow of execution at runtime.

SCOPE

The set of active bindings at any point in time is known as the referencing environment.

• Determined by scope rules.

• May also be determined by binding rules.

• There are two options for determining the reference environment:

• Deep binding: choice is made when the reference is first created.

• Shallow binding: choice is made when the reference is first used.

• Relevant for dynamically-scoped languages.

STATIC SCOPING

The bindings between names and objects can be determined by examination of the

program text.

Scope rules of a program language define the scope of variables and subroutines, which is

the region of program text in which a name-to-object binding is usable.

Early Basic: all variables are global and visible everywhere

Fortran 77: the scope of a local variable is limited to a subroutine; the scope of a global variable is the whole

program text unless it is hidden by a local variable declaration with the same variable name.

Algol 60, Pascal, and Ada: these languages allow nested subroutines definitions and adopt the closest nested

scope rule – bindings introduced in some scope are valid in all internally nested scopes unless hidden by some

other binding to the same name.

CLOSEST NESTED SCOPE RULE

To find the object referenced by a given

name:

• Look for a declaration in the current

innermost scope.

• If there is none, look for a declaration

in the immediately surrounding scope,

etc.

def f1(a1):

x=1

def f2(a2):

def f3(a3):

print "x in f3: ", x

#body of f3: f3,a3,f2,a2,x in f1,f1,a1 visible

#body of f2: f3,f2,a2,x in f1,f1,a1 visible

def f4(a4):

def f5(a5):

x=2

#body of f5: x in f5,f5,a5,f4,a4,f2,f1,a1 visible

#body of f4: f5,f4,a4,f2,x in f1,f1,a1 visible

#body of f1: x in f1,f1,a1,f2,f4 visible

STATIC LINKS

In the previous lecture, we saw how we can use offsets from the current frame pointer

to access local objects in the current subroutine.

What if I’m referencing a local variable to an enclosing subroutine? How can I find

the frame that holds this variable? The order of stack frames will not necessarily

correspond to the lexical nesting.

But the enclosing subroutine must appear somewhere on the stack as I couldn’t have

called the current subroutine without first calling the enclosing subroutine.

STATIC LINKS

We will maintain information about the lexically surrounding

subroutine by creating a static link between a frame and its “parent”.

fp

f3

f4

f5

f2

f1

def f1():

x=1

def f2():

print x

def f3():

print x

def f4():

print x

f3()

def f5():

print x

f4()

f5()

f2()

if __name__ == “__main__”:

f1()

# executes first!

DYNAMIC SCOPING

Scope rule: the "current" binding for a given name is the one encountered most

recently during execution.

• Typically adopted in (early) functional languages that are interpreted.

• With dynamic scope:

• Name-to-object bindings cannot be determined by a compiler in general.

• Easy for interpreter to look up name-to-object binding in a stack of declarations.

• Generally considered to be “a bad programming language feature”.

• Hard to keep track of active bindings when reading a program text.

• Most languages are now compiled, or a compiler/interpreter mix.

DYNAMIC SCOPING IMPLEMENTATION

Each time a subroutine is called, its local variables are pushed onto the stack with

their name-to-object binding.

When a reference to a variable is made, the stack is searched top-down for the

variable's name-to-object binding.

After the subroutine returns, the bindings of the local variables are popped.

Different implementations of a binding stack are used in programming languages

with dynamic scope, each with advantages and disadvantages.

DYNAMIC SCOPING

Deep binding: reference environment of older

is established with the first reference to older,

which is when it is passed as an argument to

show.

main(p)

thres:=35

show(p, older)

thres:integer

thres:=20

older(p)

return p.age>thres

if <return value is true>

write(p)

thres:integer

function older(p:person):Boolean

return p.age>thres

procedure show(p:person, c:function)

thres:integer

thres:=20

if c(p)

write(p)

procedure main(p)

thres:=35

show(p, older)

DYNAMIC SCOPING

Shallow binding: reference environment of

older is established with the call to older in

show.

main(p)

thres:=35

show(p, older)

thres:integer

thres:=20

older(p)

return p.age>thres

if <return value is true>

write(p)

thres:integer

function older(p:person):Boolean

return p.age>thres

procedure show(p:person, c:function)

thres:integer

thres:=20

if c(p)

write(p)

procedure main(p)

thres:=35

show(p, older)