Introduction

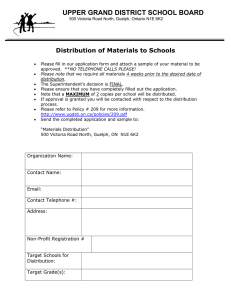

advertisement