PRICE STICKINESS AND CUSTOMER ANTAGONISM Please share

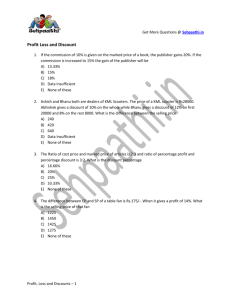

advertisement