Employment of TANF Participants in San Bernardino County: A Profile of the

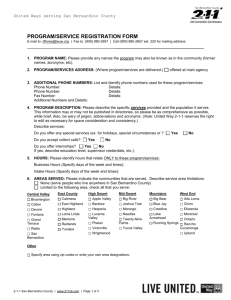

advertisement