6 Center for Corporate Ethics and Governance

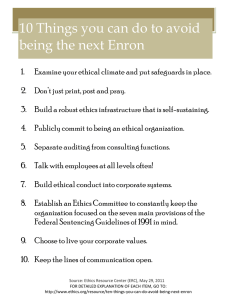

advertisement