Public Service Values:

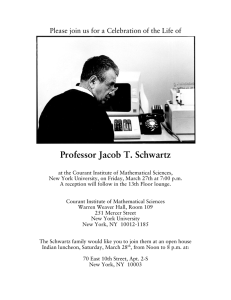

advertisement