TIBET THE JOURNAL

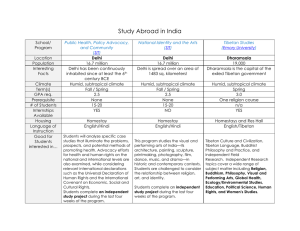

advertisement