Conifer cones:

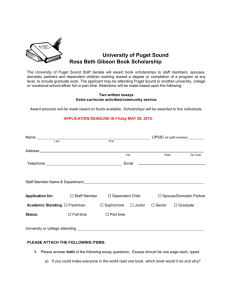

advertisement

Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Conifer cones: (1) Douglas-fir cone Pseudotsuga menziesii The Douglas-fir is the biggest tree in Washington. It can grow to more than 100 meters tall and can live for 700 years. It’s an important timber tree, and small ones are commonly grown as Christmas trees. Its needles are a favorite food of the caterpillars of many types of moths. It grows best in dry soil and full sun so it’s most common in drier climates or in disturbed areas. Around Puget Sound it is often the first coniferous tree to appear after the land is cleared. Each seed is protected by a plate-like cone scale. The part of the seed that sticks out from under the scale looks like the hind legs and tail of a mouse that has just dived beneath the scale. (2) Norway Spruce cone (3) Western White Pine cone Picea abies The Norway Spruce, native to northern Europe and the original Christmas tree, is now planted all over North America. The country of Norway donates an official gift tree each year to New York and Washington, DC. Like many large conifers, Norway Spruces live a long time—up to 600 years. Note the slender shape and fluted edges of the cone scales (plate-like structures protecting the seeds), which are characteristic of spruce cones. Most conifers are evergreens, keeping their needles through the winter. Pinus monticola The Western White Pine is a big tree, up to 70 meters tall, which grows from sea level to the mountains in this area. It has needles in bunches of five and produces the longest cone of any Washington tree. The heavy scales (plate-like structures) on the cone protect the seeds from seedeating birds and mammals. When the scales finally open, the winged seeds drop out to be blown some distance from the parent tree. Western White Pines are threatened by a fungus disease introduced from Europe that has killed 90 percent of them in this region. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Wild Things made by animals: (4) Paper Wasp nest Polistes sp. This Paper Wasp nest is made by large wasps with the ability to deliver a severe sting. They are often guarded by several females. The nest is made by a solitary female in the spring. She adds one hexagonal cell after another, laying an egg in each cell. The eggs hatch, and she brings insects, including caterpillars, for the growing larvae to eat. The larvae change into worker wasps, which help feed more of the nest-building female’s offspring. Later in summer, the first reproductive males and females appear, and the cycle begins again. (5) Caddisfly case Order: Trichoptera Caddisflies are relatively plain cousins of butterflies and moths that lay their eggs in streams and ponds. After the eggs hatch, the larvae (which look like hairless caterpillars with gills) build a case out of pebbles, pine needles or even bits of paper— anything that will stick together with silk they make themselves. Safe inside their mobile homes, they crawl around as they eat plant material or scrape algae off rocks. After several months, they crawl out of the water and fly away as adult caddisflies, leaving their mobile shelters behind. (6) American Beaver chewed branch Castor canadensis Evidence of the work of beavers might be found around the edge of any pond or lake. Beavers are nature’s civil engineers, damming streams and creating wetlands all over North America. Their big, continuously growing, front teeth can gnaw into a branch this size and drop it in a few minutes. It is then dragged to the lodge or dam being built or repaired and wedged into place. Bigger branches go first, the structure is filled in with smaller branches, and all are secured with mud. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Bird nests and eggs: (7) Rufous Hummingbird nest & eggs Selasphorus rufus Hummingbirds are the smallest birds, and their nests are about the size of a plum. After mating, the female builds a nest (often lined with lichens and spider webs to camouflage it) and lays two eggs in it. The nest is placed on top of a branch and may look like a clump of moss, well hidden from hungry egg-eating predators like jays. The eggs are incubated for 16 days before the young hatch blind and helpless. The female immediately starts to deliver a mixture of flower nectar and tiny insects to her fast-growing babies. Their eyes open in 10 days, and in just 20 days they are able to fly away from the nest. (8) Marsh Wren nest & eggs (9) Spotted Towhee nest & eggs Cistothorus palustris This small wetland bird builds its “home” in marshes, attaching its oblong nest to cattail stalks, reeds or shrubs. The woven nest is made from wet cattail reeds and grasses and is lined with cattail fluff and feathers. Males build the nests and attract females to lay their eggs in them. Marsh wrens flit through the reeds eating aquatic insects and snails. They are shy birds, much easier to hear than to see. Known for a rattle-like trill, these musical wrens can sing up to 120 different kinds of songs! Pipilo maculatus Towhees are common forest birds in Tacoma. They forage for seeds on the ground by scratching in the soil with their (relatively) big feet, and they build their nests on the ground or in low shrubs. The nest, made of twigs and grasses, has great insulating value. The female presses her brood patch (a featherless area on her belly with dense, warming blood vessels) against the eggs; the nest helps hold in the heat. When the eggs hatch, both adults bring food to the young 5 to 10 times per hour. To keep the nest clean, the parents take away fecal sacs (poop bags) produced by the young. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Arthropods (animal with no backbones, with exoskeletons, segmented bodies and jointed appendages): (10) Darner dragonfly Family: Aeshnidae Darners are some of the fastest and biggest local dragonflies, with possible wingspans of more than ten centimeters. Sometimes called “mosquito hawks,” they can fly up to 35 miles per hour! After hatching from eggs laid in the water, dragonflies begin life as larvae nabbing insects at the bottom of ponds with a powerful lower “lip.” After spending a year underwater, the larva crawls out onto a reed or stick, sheds its outer skin, and begins the second (and much shorter) part of its life as a flying insect. Adult dragonflies live 4 to 6 weeks. The Common Green Darner was voted Washington’s state insect in 1997 by elementary school students. (11) Shore Crab Hemigrapsus sp. There are two common species in the Puget Sound area that essentially look alike. These small crabs (the largest are only about six centimeters across) of the intertidal zone stay under rocks when the tide is out, hiding from gulls and other sea birds, their main predators. The female lays eggs and carries them with her for 3 to 4-1/2 months before they hatch. These crabs spend the first month of their lives as tiny plankton floating in Puget Sound before they return to the beach, where they eat mostly algae that they scrape from rocks with their big front claws. If a predator grabs a shore crab by the leg, the leg will drop off so the crab can get away, and another leg will grow in its place. If you pick one up, hold it on the flat of your palm to avoid a painful pinch. (12) Ground Beetle Family: Carabidae Among the most common and least understood insects are the ground beetles. Frequently thought of as “bad bugs,” these insects are a gardener’s friend because they eat slugs, snails and cutworms. Active at night, these beetles use their antennae to sense food and danger. Ground beetles begin life as eggs laid in the soil, then hatch out as larvae. It takes about one year for the mealworm-like larva to become an adult beetle. About 2,000 species of ground beetles live in this country. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Animal pelvises (the pelvis is the bone that connects the leg bones to the backbone): (13) Opossum pelvis (14) Great Blue Heron pelvis (15) Bullfrog pelvis Didelphis virginiana Opossums, our only local marsupial, are common in Tacoma, but because they are active at night, they are rarely seen except as road kills. The opossum pelvis is called the innominate bone, meaning bone without a name. This bone is actually made up of three bones on each side. All of them come together at the socket where the leg attaches. The pelvis offers a wide point of attachment for the large muscles that support the trunk and move the legs, hips and tail, and is attached to the backbone. Ardea herodias Great Blue Herons feed on fish along the shores of Puget Sound and in freshwater wetlands. The synsacrum is the name for the fused pelvic bone, which is made up of three different bones on each side. The pelvis is fused to the backbone as part of the strong “box of bones” that makes up a bird’s body. This synsacrum provides a firm foundation for attachment of the muscles that work the bird’s long legs. From a common reptile ancestor, the bird pelvis has evolved to become a very different structure than that of reptiles or mammals, yet the socket for the femur, the upper leg bone, shows their similarity. Lithobates catesbeianus Bullfrogs are common inhabitants of lakes and ponds all around Puget Sound. They are an introduced species, not native to the area, and their loud “jug-o-rum” calls announce their presence. Frogs have the same three paired pelvic bones as birds and mammals, but the side bones are long and strong to support the big leg muscles that are very important for jumping. Bullfrogs rest on the shore but when approached by a potential predator, they make a huge leap into the water and swim quickly to the bottom with their big webbed feet. After a while, they slowly rise to the surface. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Echinoderms (marine invertebrates with tube feet and body parts arranged in 5 sections around a central point): (16) Ochre Sea Star Pisaster ochraceus Ochre Sea Stars are key predators, overcoming mussels, barnacles, limpets, snails and other prey by pulling their shells apart with their strong tube feet (hollow tubes that act as suckers). Sea stars eat by pushing their stomach out of their mouths and into their prey. The sea stars actually digest their prey while it is outside of their body! Most Ochre Sea Stars found in Puget Sound are purple, while the ones on the outer coast are ochre-colored, a shade of orange-brown. (17) Sand Dollar Dendraster excentricus Sand dollars are flat sea urchins with tiny spines that allow them to move very slowly. They live mostly buried in sand, often anchoring one part of the shell into the sand so they can feed tipped up at an angle. The small dove-shaped pieces are part of what is called “Aristotle’s lantern”—a set of five jaws and teeth. Lines of tiny tube feet carry small organic particles to their mouth in the center of the body. The lines where the tube feet were located can be seen on the bottom of the shell. The sea-star pattern on top of the shell is where additional tube feet were located—their job is to help the animal take in oxygen. Like many marine animals, sand dollars release their eggs and sperm directly into the water to breed. (18) Sea Urchin Strongylocentrotus sp. Sea urchins live in the intertidal zone where they crawl slowly over rocks grazing on algae. There are three species of sea urchins in the Puget Sound and the Strait of Juan de Fuca: red, purple and green. Inside the shell, sea urchins have a complicated structure called an Aristotle’s lantern with five “jaws” that allows them to scrape food off of rocks and chop it into tiny bits. The red species is the largest sea urchin in Puget Sound, and its long spines keep most predators away from it. After urchins die, their spines fall off leaving the globe-like test, the hard shell that encloses the urchin. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Sea snails: (19) Moon Snail (20) Leafy Hornmouth (21) Hairy Triton Euspira lewisii Common in sandy areas around Puget Sound, this is the largest known species of moon snail in the world. As it crawls over the sand, the snail’s body seems impossibly large for the shell it belongs to. But it can withdraw completely inside its shell, blocking the "exit” with a plate called an operculum (the amber-colored thin “door” found with this specimen, which is made of keratin like your fingernails). Moon snails lay about 100,000 eggs in a spectacular “sand collar” made of sand and mucous, which looks like a sandy rubber plunger when you find one on the beach. Ceratostoma foliatum This predatory snail eats barnacles and bivalves (such as clams and mussels). It drills into its prey with a file-like structure called a radula, which grinds right through the shellfish shell. The snail then pushes digestive juices inside its prey’s shell and sucks out the digested tissue. If a Leafy Hornmouth is knocked off a rock, the shape of its shell causes it to spin through the water so that it often settles with the opening facing downward, keeping its vulnerable body away from predators. Fusitriton oregonensis This is the largest snail commonly found in Puget Sound. The hairy outer covering that protects the shell and provides camouflage is called a periostracum. Making their home in deeper water, Hairy Tritons are not often found by beachcombers. This species is a predatory snail that eats mollusks, sea squirts and even sea urchins. Its distinctive egg masses look like sheets of sawed-off, clear grains of corn packed into a spiral pattern. The microscopic larvae can remain swimming for up to 4 years before they develop into adults! Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Teeth and jaws: (22) Big Skate teeth Raja binoculata Big Skate teeth are arranged in more than 70 rows and replaced as they wear out. Skate, ray and shark skeletons are made of cartilage, so both the upper and lower jaws are cartilage, not bone. These teeth come from a very large ray, up to two meters in length. This shark relative is common in Puget Sound and often seen by scuba divers. It swims slowly just above the sea bottom by flapping its wide pectoral fins as it forages for shellfish, squid and small fish. The tiny, pointed teeth help it hold and crush prey. Big skate eggs are among largest of any skate or ray and are sometimes found on beaches. They lay them in large egg capsules that look like small greenish brown pillows, which are sometimes called “mermaid’s purses.” (23) Salmon jaw Oncorhynchus sp. These jaws come from a salmon about a half meter long. It’s easy to find such bones on the shores of streams where these fish spawn all around Puget Sound. After spending a few years at sea, the adult salmon make their way up the same river where they hatched. The males develop large hooked jaws and sharp teeth to fight one another for access to females and breeding sites. They breed, and then they die. Salmon lay their eggs in gravel nests called redds. When the young emerge in the spring, some species develop and grow in the river until they are old enough to go to sea and repeat the cycle. Meanwhile, the carcasses of the adult fish add nutrients to the river ecosystem. (24) American Beaver jaw Castor canadensis The big front incisor teeth of a beaver are orange in color due to iron in the tooth enamel. The front of each tooth is harder than the back, so the back continually wears away as the beaver gnaws into tree trunks and branches, keeping the teeth sharp. A beaver must continually gnaw because the teeth never stop growing. Although they prefer willows and aspen, they eat bark from a variety of trees and also feed on many water plants. If their pond ices over in winter, beavers feed on the twigs and branches that they stored in their cozy lodge during the summer. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Vertebrae (backbones that form the spinal column): (25) Black-tailed Deer vertebrae Odocoileus hemionus Deer are more and more often seen in the city; they make use of parks and ravines to forage for plants, especially the new growth on trees and shrubs. They also eat grass, fruit, nuts, fungi, lichens and garden plants. Like cows, deer are ruminants, meaning that after they chew their food and swallow it, it is softened in a stomach called the “rumen.” The food is then returned to the mouth and chewed again. Watch closely and you will see deer chewing their “cud”—this softened food. Deer food passes through a series of four stomachs before it is fully digested. Deer walk on the tips of their toes, which are hidden inside their hooves. (26) Great Horned Owl vertebrae Bubo virginianus January and February are good months to listen for the Great Horned Owl’s call, which people say sounds like, “Who’s awake, me tooooo.” Owls nest in forested parks and ravines. Great Horned Owls are named for the tufts of feathers that stand up on their heads for camouflage but are neither horns nor ears. The owl’s primary feathers are edged with fringes. Because of how air flows over the fringe, owls can fly silently, making it easier for them to sneak up on their rodent prey. Owls cannot move their eyes from side to side—which results in their staring gaze. Their 14 neck vertebrae allow them to swivel their heads around 270 degrees (360 degrees is a complete circle). (27) Salmon vertebrae Oncorhynchus sp. These vertebrae come from a salmon about a half meter long. It’s relatively easy to find such bones on the shores of streams where these fish spawn all around Puget Sound. After spending a few years at sea, the adult salmon make their way up the same river where they hatched. The males develop large hooked jaws and sharp teeth to fight one another for access to breeding sites and females. They breed (spawn) and then they die. The eggs are laid in gravel nests called redds. When the young emerge in the spring, some species develop and grow in the river for a year until they are old enough to go to sea and repeat the cycle. Other species return to salt water almost immediately. Meanwhile, the carcasses of the adult fish add nutrients to the river ecosystem. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Bird skulls: (28) Double-crested Cormorant skull (29) Surf Scoter skull (30) Great Blue Heron skull Phalacrocorax auritus Double-crested Cormorants can be seen all around Puget Sound in winter. They roost on docks, piers and boats and are in the water only when foraging. They dive from the surface to chase and capture fish underwater. Their hooked upper bill helps them grab and hold especially large fish, some as long as and thicker than their neck. Cormorants are closely related to pelicans, and like pelicans, have a flexible lower jaw that bows out, allowing them to swallow fish whole. The unusual pointed bone at the back of the skull is called an occipital style, an additional bone for attachment of the large jaw muscles that are used to grasp large fish. Melanitta perspicillata Surf Scoters are common winter visitors to salt water all around Puget Sound, where they dive below the water’s surface to look for mussels, other bivalves and a wide variety of other marine invertebrates. Scoters pull small mussels right off the rocks or pilings to which they are securely attached. Scoter bills are thick and strong, and the ridges on the edges of the bill gives the bird a better hold on mussels and other slippery prey. The base of the bill is swollen only in adult males, probably to better display the bright colors on the bill. Ardea herodias The bill of a Great Blue Heron is used to capture or even spear its prey. It is heavy enough to add momentum to the bird’s strike. The nostril openings are prominent because birds need to take in a lot of oxygen. There are grooves at the back of the skull for the big muscles that work the jaws. The hole in the back of the skull is where the spinal cord exits from the brain. The brain cavity isn’t very large, and that’s why “bird-brain” is not a compliment. You can also see the holes where nerves pass from the eyes through to the brain. Lesson 1: Nature Journals—Naturalists-in-Training Wild Things Key Tree seeds: (31) Bigleaf Maple samaras (32) Red Alder cones, catkins (33) Garry Oak acorns Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maples grow in moist woodlands and are usually associated with coniferous trees. They are one of the largest deciduous trees in our area. This tree’s rough bark makes it a good place for ferns and mosses to grow. Its seeds are called samaras, and the “wings” on them allow the seeds to twirl like a helicopter propeller as they fall. They can be blown some distance by the wind, and they may eventually sprout in the shade of another tree. Alnus rubra Red Alders are mid-sized deciduous trees that are common around Puget Sound, often found in areas that have been disturbed by logging or development. Red Alder roots hold bacteria that take nitrogen from the air and turn it into compounds that make the soil more fertile, benefitting all plant life. Their tiny seeds are produced in little cones, but alders aren’t related to the cone-bearing pines and firs (conifers). The slender catkins contain the male flowers, and the wind takes their pollen into the air where it reaches the female cones and fertilizes the seeds. When boiled, alder bark produces a red dye that Native Americans used to color their fishing nets to make them harder to see under water. Quercus garryana An acorn is the “fruit” of an oak tree, or to put it another way, an oak’s way of making another oak. After they ripen, acorns fall, sometimes carpeting the ground under their parent tree. If they were all to sprout there, each seedling would have little chance of survival, competing for light and nutrients with the parent tree and all the other seedlings. However, nutritious acorns are a favorite food of many animals including squirrels and jays. These animals gather acorns and hide them to keep for winter-time meals. Some of these hidden acorns don’t get eaten and end up sprouting into oak seedlings far away from their parent trees.