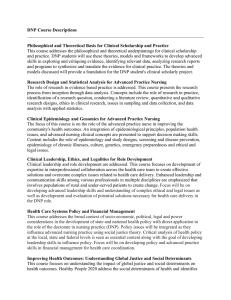

The DNP by 2015

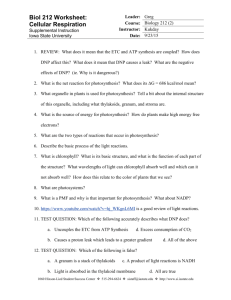

advertisement