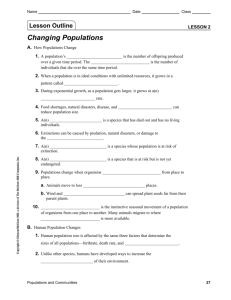

E n h a n c i n g ... f o r S p e c i...

advertisement