6 The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research om as

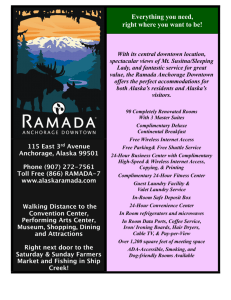

advertisement