The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that research and analysis.

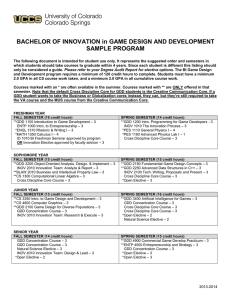

advertisement