Indicator 1.05. Number and Status of Native Forest-Associated Species at Risk,

advertisement

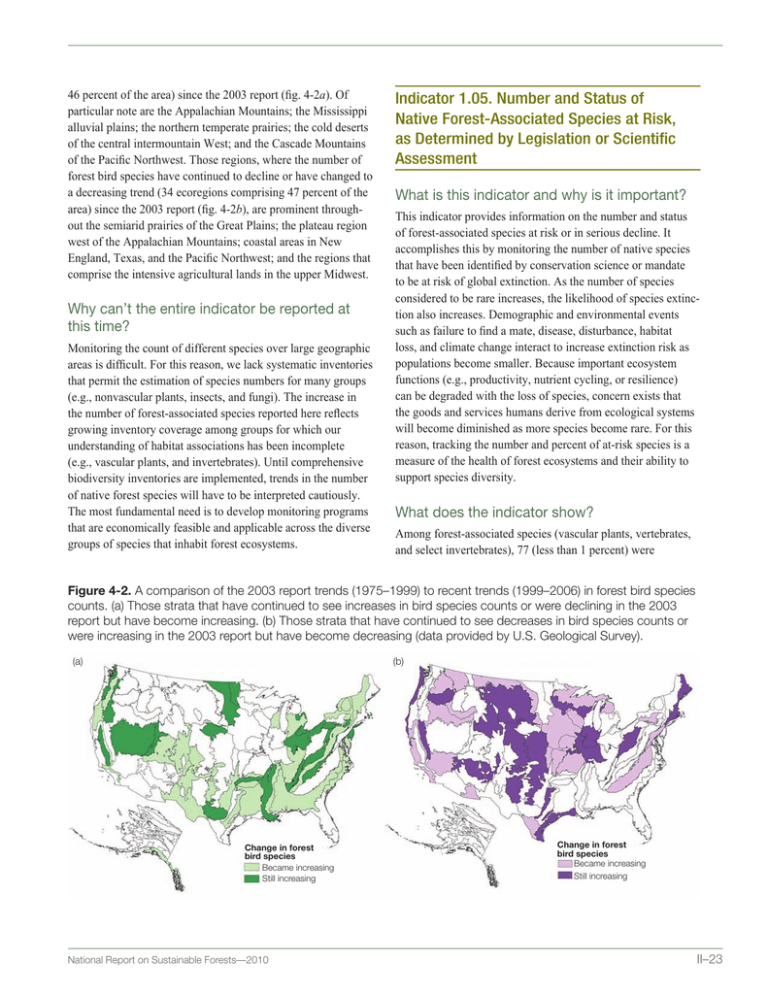

46 percent of the area) since the 2003 report (fig. 4-2a). Of particular note are the Appalachian Mountains; the Mississippi alluvial plains; the northern temperate prairies; the cold deserts of the central intermountain West; and the Cascade Mountains of the Pacific Northwest. Those regions, where the number of forest bird species have continued to decline or have changed to a decreasing trend (34 ecoregions comprising 47 percent of the area) since the 2003 report (fig. 4-2b), are prominent throughout the semiarid prairies of the Great Plains; the plateau region west of the Appalachian Mountains; coastal areas in New England, Texas, and the Pacific Northwest; and the regions that comprise the intensive agricultural lands in the upper Midwest. Why can’t the entire indicator be reported at this time? Monitoring the count of different species over large geographic areas is difficult. For this reason, we lack systematic inventories that permit the estimation of species numbers for many groups (e.g., nonvascular plants, insects, and fungi). The increase in the number of forest-associated species reported here reflects growing inventory coverage among groups for which our understanding of habitat associations has been incomplete (e.g., vascular plants, and invertebrates). Until comprehensive biodiversity inventories are implemented, trends in the number of native forest species will have to be interpreted cautiously. The most fundamental need is to develop monitoring programs that are economically feasible and applicable across the diverse groups of species that inhabit forest ecosystems. Indicator 1.05. Number and Status of Native Forest-Associated Species at Risk, as Determined by Legislation or Scientific Assessment What is this indicator and why is it important? This indicator provides information on the number and status of forest-associated species at risk or in serious decline. It accomplishes this by monitoring the number of native species that have been identified by conservation science or mandate to be at risk of global extinction. As the number of species considered to be rare increases, the likelihood of species extinction also increases. Demographic and environmental events such as failure to find a mate, disease, disturbance, habitat loss, and climate change interact to increase extinction risk as populations become smaller. Because important ecosystem functions (e.g., productivity, nutrient cycling, or resilience) can be degraded with the loss of species, concern exists that the goods and services humans derive from ecological systems will become diminished as more species become rare. For this reason, tracking the number and percent of at-risk species is a measure of the health of forest ecosystems and their ability to support species diversity. What does the indicator show? Among forest-associated species (vascular plants, vertebrates, and select invertebrates), 77 (less than 1 percent) were Figure 4-2. A comparison of the 2003 report trends (1975–1999) to recent trends (1999–2006) in forest bird species counts. (a) Those strata that have continued to see increases in bird species counts or were declining in the 2003 report but have become increasing. (b) Those strata that have continued to see decreases in bird species counts or were increasing in the 2003 report but have become decreasing (data provided by U.S. Geological Survey). (a) (b) Change in forest bird species Became increasing Still increasing National Report on Sustainable Forests—2010 Change in forest bird species Became increasing Still increasing II–23 determined to be presumed or possibly extinct, 4,005 (27 percent) were determined to be at-risk of extinction (includes species that are critically imperiled, imperiled, or vulnerable to extinction), and 10,576 (71 percent) were determined to be apparently secure. The percentage of forest-associated species in each conservation status category varies by taxonomic group (fig. 5-1a). The number of possibly extinct and at-risk species is proportionately greatest among select invertebrates (32 percent), followed by vascular plants (28 percent), and vertebrates (16 percent). Within forest-associated vertebrates, the greatest proportion of possibly extinct and at-risk species is found among amphibians (34 percent). Birds (14 percent), freshwater fishes (12 percent), mammals (11 percent), and reptiles (11 percent) show proportionately lower numbers of species that are of conservation concern. At-risk species that are associated with forest habitats are concentrated geographically in Hawaii, the arid montane habitats of the Southwest, chaparral and sage habitats of Mediterranean California, and in the coastal and inland forests of northern and central California (fig. 5-1b). What has changed since 2003? Since the 2003 report, a broader accounting of species that inhabit forests has resulted in an increase in the number of species that are considered possibly extinct or at risk of extinction, with the greatest increase reported among vascular plants (3,644 more species). The number of species of conservation concern also increased among select invertebrates (108 more species) and vertebrates (23 more species). The sizable percentage gains among vascular plants and invertebrates (fig. 5-2a) are largely attributable to newly available data rather than from a real increase in the percentage of species consider at risk. Among the relatively well-studied vertebrates, an increase of about 0.8 percent has occurred since the 2003 report. Among vertebrate species groups (fig. 5-2b) the greatest percent gains in species thought extinct or at risk of extinction were observed among amphibians (an increase of 2.2 percent), followed by mammals (an increase of 1.0 percent), reptiles (an increase of 0.9 percent), and birds (an increase of 0.5 percent). Why can’t the entire indicator be reported at this time? Information on the conservation status of obscure species is lacking in many cases. Among all species (not just forest associated), 281 (1.7 percent) vascular plant, 14 (less than 1 percent) vertebrate, and 660 (9.0 percent) invertebrate species (select groups) have not been, as yet, assigned a conservation status category nor a habitat affinity. Given the number of species for which conservation status ranks are forthcoming, trends in the number of forest-associated species by conservation status will need cautious interpretation because gains are expected as unranked species are evaluated. Regional trend analyses were also limited by the fact that the ecoregional stratification changed from the 2003 to the 2010 reports. Figure 5-1. (a) The percent of vascular plant, vertebrate, and invertebrate species associated with forest habitats determined to be possibly extinct, at risk of extinction, secure, or unranked. (b) The percentage of forest-associated species (vascular plants, vertebrates, and select invertebrates) occurring in each ecoregion determined to be at risk of extinction (does not include species classified as possibly extinct). (2009, data provided by NatureServe.) (a) (b) 100 Percent of species 80 60 40 20 0 Vascular plants Unranked II–24 Secure Vertebrates At-risk Invertebrates Possibly extinct Percent 0–1.6 >1.6–3.3 >3.3–8.8 >8.8–12.3 >12.3–66.5 National Report on Sustainable Forests—2010 Figure 5-2. A comparison of the percent of forest-associated species that have been determined possibly extinct or at risk of extinction between the 2003 and 2010 reports among (a) vascular plants, vertebrates, and select invertebrates, and (b) among the relatively well-known mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, and freshwater fish species groups. Because the conservation status of forest-associated freshwater fish species (▲) were unavailable for the 2003 report, only a single-point estimate for the 2010 report is shown. (Actual reporting dates were 2002 and 2009.) 35 35 (b) 30 30 25 25 Percent of species Percent of species (a) 20 15 20 15 10 10 5 5 Vascular plants Vertebrates Invertebrates 0 Mammals Birds Reptiles Amphibians Fishes 0 2003 report 2010 report Indicator 1.06. Status of Onsite and Offsite Efforts Focused on Conservation of Species Diversity What is the indicator and why is it important? This indicator provides information that describes onsite and offsite efforts to conserve species diversity. Onsite conservation efforts are those implemented within the forest. Offsite conservation efforts are usually measures of last resort which may move a species from its natural habitat or range to specially protected areas or into captivity as part of a breeding program or collection. Some forest species and habitats may have declined to such an extent that intervention is required to safeguard them for the future. As a result of the biological diversity losses caused by human pressure, different sectors of society (governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and individual citizens) are increasingly involved in conservation measures. These conservation initiatives include scientific studies about species at risk, keystone species assessments, laws, and projects that reinforce conservation of biological diversity, forest restoration, and connectivity. It is more practical to estimate expenditures associated with efforts to conserve biological diversity than to directly measure the results of those efforts. Expenditures by public agencies directed at conservation of biological diversity fall into four National Report on Sustainable Forests—2010 2003 report 2010 report broad categories: (1) research associated with biological diversity, including among others, knowledge about keystone species, threatened species, functional groups, and spatial distribution; (2) environmental education and information about the importance of biological diversity, and (3) conservation projects related to habitat restoration and biological diversity management. A fourth category of this indicator is (4) the proportion of forest area managed for biological diversity conservation, outside of protected areas, relative to total forest area. This indicator is closely related to Indicators 1.02 and 1.09. What does the indicator show? Federal expenditures for research, education, and management associated with conservation of forest biological diversity are concentrated in five Federal agencies: 1.Forest Service 2.National Park Service 3.Bureau of Land Management 4.U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 5.U.S. Geological Survey In combination, those agencies spent approximately $2 billion in 2008 on research, education, and management that fosters conservation of forest biological diversity (fig. 6-1). These expenditures are the equivalent of $2.68 for every acre of forest land in the United States State natural resource agencies and hundreds of NGOs make additional expenditures associated II–25