Fire Management Assessment of Eastern Province, Zambia Technical Report January 2015

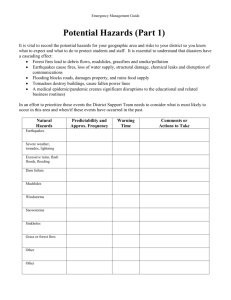

advertisement