O Perspective Harnessing Private-Sector Innovation to Improve Health Insurance Exchanges

advertisement

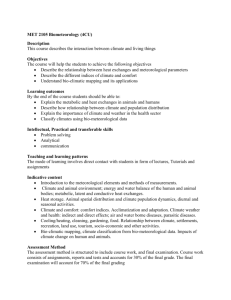

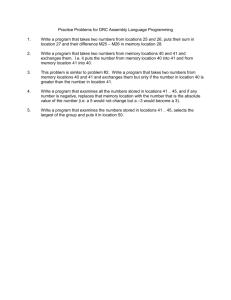

Perspective C O R P O R AT I O N Expert insights on a timely policy issue Harnessing Private-Sector Innovation to Improve Health Insurance Exchanges Carole Roan Gresenz, Emily Hoch, Christine Eibner, Robert S. Rudin, Soeren Mattke O verhauling the individual health insurance market— as regulation of insurers, eligibility determination, and transfer including through the creation of health insurance of subsidy payments to insurers) but allows the private sector to exchanges—was a key component of the Patient assume responsibility for more-peripheral exchange functions, Protection and Affordable Care Act’s multidimen- such as developing and sustaining exchange websites (both the sional approach to addressing the long-standing problem of the technical architecture and the software overlays that support plan uninsured in the United States (Public Law 111-148, 2010). Despite comparison and enrollment). Although private-sector entities have succeeding in enrolling millions of Americans, the exchanges already stepped into these exchange-related functions on a limited have confronted and still face several challenges, including poor basis, privately facilitated exchanges could conceivably relieve the consumer experience, high operational and development costs, and government of its responsibility for so-called front-end website incomplete market penetration. operations and consumer decision-support functions entirely. In this perspective, we consider a different model for Although we do not offer a formal and conclusive assessment the exchanges—a model that we term privately facilitated of the costs and benefits of this model, our analysis suggests that exchanges—which has the potential to address these challenges a shift to privately facilitated exchanges could improve consumer and deepen the Affordable Care Act’s impact. In this model, the experience and, consequently, increase enrollment, and lower government retains control over sovereign exchange functions (such costs for state and federal governments. A move to such a model [W]e consider a different model for the exchanges—a model that we term privately facilitated exchanges—which has the potential to address these challenges and deepen the Affordable Care Act’s impact. Public Insurance Expansion requires, nonetheless, managing its risks, such as reduced consumer District of Columbia) adopted Medicaid expansion; six states were protection, increased consumer confusion, and the possible lack of debating expansion; and 16 had elected not to expand (Paradise, a viable revenue base for privately facilitated exchanges, especially 2015). Between October 2013 and December 2014, Medicaid in less populous states. On net, we believe that the benefits are and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment The Affordable Care Act expands public insurance by allowing states to extend Medicaid eligibility to anyone with an income below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and offering federal subsidies to states to cover most of the costs associated with covering the newly eligible. As of January 2015, 29 states (plus the large enough and the risks sufficiently manageable to seriously increased by more than 10.7 million people in 49 states (Centers for consider such a shift; we intend for this perspective to stimulate Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2015).1 further discussion. In the rest of this paper, we provide background information and more detail on our assessment. Individual Mandate A Brief Overview of the Affordable Care Act Additionally, the Affordable Care Act imposes a penalty on A primary objective of the Affordable Care Act was to address the people who are not covered by insurance (with some exceptions). long-standing problem of the uninsured. In 2011, approximately The penalty in 2014 was $95 per adult and half that amount per 50 million Americans—roughly 16 percent of the population—had child up to a maximum of $280 per family or 1 percent of family no health insurance coverage (Office of the Assistant Secretary for income, whichever was greater. Penalties increase each year and, Planning and Evaluation, 2014). To improve coverage, Affordable in 2015 (2016), are $325 ($695) for an adult and half that per Care Act provisions tackled fundamental issues relating to the child up to a maximum of $975 ($2,085) per family or 2 percent availability and affordability of insurance. The law broadened the reach of public insurance, requiring most Americans to have health (2.5 percent) of income, whichever is greater. The law exempts insurance or face a penalty (the so-called individual mandate), people from the penalty who do not obtain coverage because they establishing health insurance exchanges, providing for a subsidy for cannot afford it. the purchase of individual coverage, and putting in place a suite of insurance regulations. 1 2 Connecticut and Maine did not report data. Exchanges [A] state may run its own exchange, participate in a federal exchange, or partner with the federal exchange. The Affordable Care Act requires the establishment of exchanges that allow people to purchase individual health insurance plans but provides states with latitude regarding the implementation of the exchange.2 In particular, a state may run its own exchange, participate in a federal exchange, or partner with the federal 100 and 133 percent of the FPL, at 3 to 4 percent of income for exchange (Dicken, 2013). In 2015, 13 states and the District of those with incomes between 133 and 150 percent of the FPL, and Columbia fully operated their own exchanges (called state-based at an increasing percentage of income for higher income levels, up marketplaces). Another three states performed all core functions to 9.5 percent of income for those with incomes between 300 and of state-based exchanges but relied on the federal government’s 400 percent of the FPL. For families with incomes between 100 information technology platform to handle eligibility determina- and 250 percent of the FPL, cost-sharing subsidies further limit tion and enrollment (called federally supported state-based market- out-of-pocket expenditures for care, although these subsidies apply places). Among the 34 states that relied on the federal exchange, only to those who purchase a silver-level plan (Andrews, 2013). seven partnered with the federal government by performing plan Consumers can apply subsidies only to qualified health plans management, consumer-assistance tasks, or other activities (called (QHPs) bought on the exchanges as described below. In King v. state partnership marketplaces). The remaining 27 states relied Burwell, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the Affordable solely on the federal government for all exchange-related tasks Care Act’s subsidies in all states, regardless of whether the state (called federally facilitated marketplaces) (Dash, Monahan, and operates its own exchange or relies on or partners with the federal Lucia, 2013). exchange. Subsidy Insurance Market Regulation The Affordable Care Act provides a subsidy for people who The Affordable Care Act established a suite of regulations related to purchase health insurance coverage through the exchanges if they plans sold on the individual market, including the following: have income between one and four times the FPL, are ineligible • It requires that plans cover a minimum basket of specified for Medicaid, and have no affordable employer offer. The federal essential health benefits (Center for Consumer Information government subsidizes premiums in the form of a tax credit. It caps and Insurance Oversight, undated). premiums at 2 percent of income for those with incomes between • It establishes guaranteed issue and renewability. • It removes preexisting-condition coverage exclusions. Our focus is on the individual exchanges, although the Affordable Care Act also established exchanges for small businesses. 2 • It prohibits insurers from using health status to rate premiums. 3 Figure 1: Individual Market Policies • It allows insurers to vary premiums based only on age, region, family structure, and smoking status. • It limits the amount of variation in premium by age (to a l policies, includ idua ing div n i no l n– Al Af f • It requires regulatory review of annual health insurance premium increases. The regulations also aim to increase transparency for consumers by requiring that plans sold through the individual market have standardized actuarial values (catastrophic, bronze, silver, gold, and platinum). Most of the Affordable Care Act’s regu- Subsidyeligible QHPs, i.e., bought on the exchange Care Act implem e n ble tat rda ion fo Af for smokers versus nonsmokers). es bands, not including children) and by smoking status (1.5-to-1 e or 3-to-1 maximum for people in the oldest versus youngest age t–compliant polic e Ac ies Car so e ld bl re Act–compli a a be C e ant d l r b f a o p d r o lic fo i QHPs Af lations apply to all individual market plans, whether those plans are sold on the exchanges or not (i.e., “off” exchange). However, all plans sold on the exchanges must be QHPs, a designation that requires adherence to additional requirements. QHP requirements NOTE: The figure is illustrative only; ring sizes do not reflect distribution of individual policies by type. include ensuring adequacy of provider networks, inclusion of RAND PE152-1 essential community providers in the network, and accreditation with respect to quality measures. Although insurance providers in the form of government contracts to private entities to develop can sell QHPs off the exchanges, the federal government makes exchange components. Figure 2 depicts, at a high level, typical subsidies available only for QHPs purchased on the exchanges. flows of information and the interactions among consumers, Figure 1 illustrates the universe of individual policy types. insurers, the exchanges, and the federal Data Services Hub (described below). Exchange Functions The Affordable Care Act requires that exchanges perform a set Eligibility and Enrollment of core functions, including eligibility and enrollment, plan management, and consumer assistance (Dicken, 2013; Barkakati Exchanges share information with the federal Data Services Hub and Wilshusen, 2014). Both the federal and state exchanges have in real time to determine whether someone is eligible to purchase a been developed through public–private collaboration, primarily plan on the exchange; enroll in Medicaid or CHIP; enroll in other 4 government health care or health insurance programs; or receive is responsible for making subsidy payments to issuers for enrollees a subsidy and, if so, its amount. The exchange must also facilitate in both state exchanges and the federal exchange. enrollment in Medicaid or CHIP by transmitting information for eligible people to a state agency and must enroll them in the Plan Management QHPs they have chosen (Dicken, 2013). The Data Services Hub Exchanges must have processes for insurers to apply to offer a supports eligibility determinations by accessing information from health plan on the exchange, to determine whether a health plan government agencies, such as the Social Security Administration, meets QHP standards, and for ongoing review and oversight the Internal Revenue Service, and DHS, to confirm Social Security (Dash, Lucia, et al., 2013).3 The QHP application process is a number, income, citizenship, and the like. The federal government critical and complex part of plan management because it ensures that offered policies meet the standards and may be subsidized. Figure 2: Information Flows and Interactions In short, the plan provider must submit a series of interlocking Among Entities in Exchange Functions, Current templates for each plan. The documentation requirements are State tors, and providers must compile the documentation in a short time • Determines eligibility • Enrolls the consumer • Manages plans • Supports the consumer frame between the release of the federal guidance documents and the QHP submission window. at io Sends applicant information Fi le sr at e an d pl a n in f or m Issues coverage n Tr a ns fe rs a pp lic at io n Consumer considerably more complex than prior requirements of state regulaExchange Seeks out coverage options Insurer Transfers subsidy Consumer Assistance Returns information to exchanges Consumer-assistance functions for exchanges include provision of a website, decision-support tools to enable comparison of Federal Data Services Hub available QHPs and the impact of any subsidy, a toll-free hotline • Connects with the Social Security Administration, DHS, and other federal agencies • Verifies the consumer’s identity • Connects with state agencies to determine eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP • Determines eligibility for other health care coverage • Determines eligibility for an exchange purchase • Determines subsidy eligibility and amount and in-person assistance, a navigator program to provide impartial information about the exchanges and help people select plans, and 3 States that chose to operate their own exchanges had flexibility regarding various aspects of the exchanges, and one of the ways in which they varied was in terms of how they recruited or limited insurers participating in the exchanges and plans offered on the exchanges. Maryland, for example, explicitly required that certain insurers participate in the exchange; to limit the choices that consumers faced, the District of Columbia adopted policies to ensure that the exchange offered only substantially distinct plans. NOTE: DHS = U.S. Department of Homeland Security. RAND PE152-2 5 outreach activities (Fernandez and Mach, 2013). Decision support Planning and Evaluation, 2015a). Premium rates in 2014 were includes website functionality, such as filtering of plans based on considerably lower for exchange plans than for plans offered in selected features (e.g., actuarial value or so-called metal type), the individual market before Affordable Care Act implementation premium, deductible, and insurance company. Some exchanges (Skopec and Kronick, 2013), and most consumers had access to provide quality information for plans (Dash, Lucia, et al., 2013). coverage costing less than $100 in out-of-pocket (postsubsidy) premiums (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and An Alternative Model of Public–Private Evaluation, 2015a). Further, premium increases between 2014 and Collaboration 2015 have been modest (2 percent for the second-lowest-cost, or The exchanges were designed, developed, and created in a relatively silver, plans) (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2015a). short period; millions of people enrolled in health insurance Without diminishing these successes in expanding and coverage through the exchanges; most consumers shopping on improving the individual market, it is important to recognize the exchanges have had choices among issuers; and premiums on room for improvement. Evidence points to the existence of a the exchanges have been lower than expected. By October 2014, sizable untapped market of consumers who are eligible for but not 6.7 million people were signed up for health insurance coverage enrolled in health plans, including young adults: Approximately through the exchanges, and enrollment reached 11.7 million 15 million Americans who were uninsured in 2014 were eligible to in 2015 (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and purchase coverage through the exchanges (Office of the Assistant Evaluation, 2014, 2015b). By December 26, 2014, 14 months Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2014). Further, young after the exchanges went live, HealthCare.gov hosted more than adults, in particular, continue to have relatively high uninsurance 15 million unique visitors (by comparison, Pinterest took almost rates—24 percent of adults ages 26 to 34 remained uninsured as two years to reach that volume) (Constine, 2012). In 2014, of the third quarter of 2014 (Levy, 2014). At the same time, the 74 percent of consumers were able to choose from three or more exchanges have faced criticism over the quality of the consumer issuers, and federal officials expect that percentage to rise to more experience and have experienced significant technical challenges than 90 percent in 2015 (Office of the Assistant Secretary for and high development costs (Dicken, 2013; Baker et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2014b; Venkatesh, Hoehle, and Aljafari, 2014). Premium rates in 2014 were considerably lower for exchange plans than for plans offered in the individual market before Affordable Care Act implementation. In light of these challenges, we consider a different model for running the exchanges—a model that we term privately facilitated exchanges—that offers the potential to address these challenges and deepen the impact of the Affordable Care Act. In particular, we discuss a model with a greater role for the private sector for 6 The advent of aggregators for auto insurance—such as Google’s Compare and Insurance.com, which provide consumers with tools for comparison shopping and coverage sign‑up—suggests that consumers are willing to use aggregator sites in the insurance market. exchange functions exclusive of those that are arguably sovereign aggregation services” (Madnick et al., 2000, p. 1). Aggregators and thus must remain under government control. These sovereign have existed for more than a decade in a diverse range of industries, functions include regulatory oversight over the insurance market; including travel, finance, and car insurance. Some of these services eligibility determinations for purchasing coverage through an have attracted millions of users by providing usable interfaces to exchange, for a subsidy, and for Medicaid or CHIP; and transfer of easily compare products. The popularity and voluntary nature subsidies to insurers. State regulators have to ensure that coverage of these aggregators suggest that customers find them valuable. products comply with state and federal law and that insurers are In some markets, multiple aggregators compete with each other. financially sound. For plans that are eligible for the subsidy, state Because they generally list the same products (suppliers have an and federal regulators must also certify their QHP designations. interest in submitting their products wherever their potential Eligibility determinations and subsidy transfers require the customers would find them), aggregators compete with each integration of sensitive data from government agencies. However, other on user experience, user satisfaction, and decision-support other exchange functions are arguably more peripheral—including functionality. The advent of aggregators for auto insurance—such operation of exchange websites, development and implementation as Google’s Compare and Insurance.com, which provide consumers of decision-support tools, data collection and synthesis to inform with tools for comparison shopping and coverage sign‑up— consumers about choices, and plan enrollment and payment—and suggests that consumers are willing to use aggregator sites in the thus might be more amenable to leveraging private-sector forces to insurance market. Innovative web-based services indicate the potential kinds of address some of the challenges the exchanges face. improvements that health insurance aggregators can achieve. Some Data Aggregators in Other Industries popular web-based companies offer a highly streamlined consumer In other industries, private-sector entities commonly perform these experience (e.g., Amazon), help simplify complex processes (e.g., types of data-aggregation functions. Companies billing themselves TurboTax), or allow for shopping with greater price and option as web aggregators, data aggregators, or simply aggregators are transparency in decisionmaking (e.g., Kayak or Expedia). Although “entities that collect information from a wide range of sources, we recognize that health insurance could be inherently more with or without prior arrangements, and add value through post complex than these services because of uncertainty about future 7 health expenditures and specialized terminology, for example, there The privately facilitated exchanges could conceivably relieve the government of its responsibility for front-end website and consumer decision-support functions entirely. is likely still room for innovation (Arnold et al., 2012). Web-Based Entities in the Health Insurance Domain Data aggregators have, in fact, begun to inhabit the exchange space (Kuranda, 2013). Several websites, commonly called web-based entities, “scrape” and synthesize data from HealthCare.gov and state over nonsovereign functions. The privately facilitated exchanges exchange websites to provide enhanced decision support (Center could conceivably relieve the government of its responsibility for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, 2014). One for front-end website and consumer decision-support functions example is HealthSherpa (Wlodarz, 2014). Originally designed as entirely. In other words, once a sufficient number of functioning an “overlay” to the federal exchange website to provide decision and financially viable exchanges have emerged, state and federal support but not enroll consumers (instead directing consumers to governments could cease operating the front ends of their the exchange after they selected a plan), the website is now part- exchanges and provide only the back-end functions of the Data nering with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Services Hub and regulatory oversight. to make the enrollment process smoother for consumers (Fung, Operationally, private-sector entities would need to coordinate 2014). HealthSherpa interacts with the exchanges to obtain plan their functions with those functions remaining under government data and with the Data Services Hub for eligibility and subsidy control. Two potential models exist for interactions with the Data determinations and payment to issuers. Other examples of these Services Hub. One would be fashioned after E-Verify,4 which services are eHealthInsurance Services, Picwell, and GoHealth. allows businesses to determine the eligibility of potential employees Web-based entities interact not only with the public exchanges and the Data Services Hub but also with insurer databases. They to work in the United States. In this model (we call it E-Subsidy), can obtain real-time information on a plan’s provider network and each exchange would interface with the federal Data Services cost data for common services and procedures. Some facilitate Hub to verify a consumer’s ability to purchase on the exchange, side-by-side comparisons of providers that are part of the network determine the consumer’s eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP, and or of different plan options and allow customized filtering of those verify the consumer’s eligibility for subsidy and the amount of any options. subsidy. Privately Facilitated Exchanges 4 Employers have the option to enroll in E-Verify and can submit data of applicants and employees for verification. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services then compares the information with immigration and Social Security Administration data to determine eligibility to work. A logical extension of web-based entities is our envisioned model of the privately facilitated exchange—that is, an exchange that takes 8 The other model would resemble the PayPal system, in which Going forward, the exchanges could directly interface with the consumer creates a single account that allows that consumer insurers to access up-to-date plan information, such as prices, to make secure payments on numerous websites. If we translate benefits, and provider networks, similar to what happens in the this model to the exchange context, the consumer would create an travel industry, in which companies make data on availability and account on a third-party private website that would hold pertinent prices available to aggregators. The government would maintain information about that consumer’s eligibility to purchase exchange control over the QHP certification process and responsibility for coverage and the amount of any subsidy. Exchanges would allow regulatory oversight of insurers, but this change would decrease consumers to link to these accounts and use them to authorize the the complexity of the QHP template, which would be reduced to transfer of their eligibility and subsidy information. a regulatory filing, and improve the accuracy and timeliness of displayed plan information. Figure 3 illustrates the data flows for Independently, the transition to privately facilitated privately facilitated exchanges under the e-subsidy operating model. exchanges could also pave the way toward greater automation of plan-management functions. Currently, insurers have to submit Figure 3: Information Flows and Interactions detailed information about health plans they intend to offer on the Among Entities in Exchange Functions, Proposed exchanges through so-called QHP templates. Those templates are E-Subsidy Model a set of linked spreadsheets into which insurers enter data, such Federal Data Services Hub as corporate information, medical, dental and pharmacy benefits, network, copayments, and premium rates. They serve a dual Transfers subsidy purpose: They constitute both a regulatory filing and a repository for plan information on the exchanges. This dual purpose creates Verifies identity; determines eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP, other programs, and exchange purchase; and determines the amount of subsidy, if any an operational challenge because the regulatory nature of the templates necessitates that they be static—i.e., errors cannot be Provide information corrected or changes incorporated quickly—but requires resubmis- Privately facilitated exchanges Consumers Seek out coverage options sion and uploading of the corrected templates during specified service windows. In other words, even if regulators and the carrier Transfer applications are aware of an error, the consumer could continue to see incorrect information for weeks. Similarly, information on a health plan Insurance regulators • Oversees insurance plans •Certifies QHPs that is dynamic by its very nature, such as network providers and their ability to accept new patients, cannot be updated in a timely fashion. RAND PE152-3 9 Provide plan information Insurers Tech Improvements Mean You Can Now Window Shop,” 2014; Greater convenience could also have the benefit of making the “Meet the Press Transcript,” 2014). exchanges a more attractive destination for consumers who seek to Decision support is a key element of the consumer experience obtain individual coverage but are not eligible for subsidies and a marketplace for insurance products beyond coverage that fulfills and is critical for helping consumers select plans that will best serve the requirements of the individual mandate, such as vision and them (Krughoff, Francis, and Ellis, 2012). Recommended best dental insurance or supplemental coverage to cover copayments. In practices in terms of decision support include the following: • providing an out-of-pocket cost calculator that enables the next section, we consider the potential benefits and risks of a consumers to estimate total annual spending, including both move toward privately facilitated exchanges. premium and out-of-pocket costs Potential Benefits and Risks • enabling sorting and filtering of plans to highlight best-fit We consider the potential advantages and challenges of moving plans and to organize options, including shortcuts to help exclusively to privately facilitated exchanges by assessing the consumers select plans quickly • highlighting summary information about what matters most model along four dimensions: (1) consumer experience, (2) choice, to consumers (3) consumer protection, and (4) cost and sustainability. • providing a directory to display health care providers particiConsumer Experience pating in each plan (Pacific Business Group on Health, 2013). The quality of consumers’ experiences with state and federal Several studies suggest that the federal exchanges have fallen government exchanges—not only with decision support related to plan choice but also the entirety of consumers’ interactions with short in terms of decision support. A systematic assessment of the exchange—has been less than optimal. Technical issues were the choice architecture of federal and state exchanges found a major problem during the first open-enrollment period. During robust sorting and filtering options but limited decision support the 2014 rollout, site glitches delayed early users—multihour (Baker et al., 2014). For example, none of the exchanges provided wait times, blank menus, and prompts and questions not relevant personalized total cost estimates (including premiums, subsidies, to their circumstances (Ornstein, 2013). Although the federal and out-of-pocket expenses); none followed recommended usability exchange was designed to provide real-time eligibility and enroll- standards (Doulgerof, 2008); none provided the choice between ment for Medicaid and CHIP, some users had to wait for extended long versus short paths to enrollment; and few had integrated periods of time to learn whether they had been granted access and, provider information (Ornstein, 2013). Between the 2014 and 2015 at times, had to reapply on their state websites. The rollout team open-enrollment periods, the choice architecture remained largely treated these performance issues as a priority, and such problems the same, although some aspects, such as sorting and filtering and have been far less common for users in 2015 (“HealthCare.gov’s quality information, improved (Ornstein, 2013). 10 The monopoly nature of the award might have limited the incentive Other studies of federal and state exchanges confirmed deficiencies with respect to the consumer experience, including health insurance jargon that can be confusing for nonexperts, overly complex filters and sorting tools for cost and coverage preferences, and an overwhelming number of options to some. to continuously improve the product. Web-based entities have endeavored to offer a more streamlined consumer experience. About 110,000 consumers have used HealthSherpa, which suggests that consumers see added value in the web service, although some experts have suggested that available decision support still falls short by some standards (Bidgood, 2015; “3%,” 2015; Sprung, 2014). According to its 2014 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings, eHealthInsurance Services serves more than 1 million members. A greater reliance on private-sector entities for the front-end Other studies of federal and state exchanges confirmed defi- exchange functions could substantially improve consumer ciencies with respect to the consumer experience, including health experience. As we pointed out, the planned and rigid nature of insurance jargon that can be confusing for nonexperts, overly government procurement processes is not ideally compatible with complex filters and sorting tools for cost and coverage preferences, the innovation and experimentation paradigms of modern web and an overwhelming number of options to some (Brownlee, 2014; design that have spawned highly user-friendly websites in many Wong et al., 2014a, 2014b). Content organization, user experience, e-commerce markets. Competition between privately facilitated graphics, and navigation have been identified as key leverage points exchanges would likely ensure innovation and product differentia- for improvement (Venkatesh, Hoehle, and Aljafari, 2014). An tion. Niche providers could emerge that focus on hard-to-reach additional limitation has been the lack of a robust mobile applica- segments, such as the young. Notably, private websites are not tion for the federal exchange, despite the fact that an estimated currently required to comply with certain government require- 25 percent of all visitors to the federal exchange arrived by mobile ments, such as accessibility for visually impaired users (Kuranda, devices (Brownlee, 2014). 2013). If private-sector entities fully assume these functions, the The government contracting process requires defining clear federal government would need to regulate to ensure accessibility specifications for deliverables up front; competition for the work for all consumers (Kuranda, 2013). based on understanding of the task, capabilities, prior experience, A better consumer experience could, in turn, help boost and cost; and award based on best value to the government at the enrollment among people who remain uninsured but are eligible time of the decision. Changes to scope, deliverables, and awardees to purchase on an exchange. The complexity of the process does require complex contract modifications, which likely limited the not deter all such people from purchasing—cost, for example, is ability to use industry best practices in software and website design. another consideration—but the ease of exchange purchase is a 11 contributing factor. Among people who remained uninsured in Figure 4: Number of Insurers Operating on Each California after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, State’s Exchange 6 percent reported that problems with the application process 1–4 were a barrier to coverage. Among the uninsured who attempted 5–8 9–11 13–16 WA to get coverage (roughly one-third of the uninsured), the majority MT ND OR found shopping for coverage difficult, with more than two-thirds ID WY reporting problems comparing plans or understanding out-of- NV pocket and premium costs (DiJulio et al., 2014). Additionally, CA in a survey of adult U.S. Latinos, among the 29 percent who reported visiting an exchange website, 5.7 percent tried to enroll SD WI AZ PA IL CO KS OK NM TX 2.3 percent did not try to enroll because doing so was too compli- OH IN MO WV KY VA NC TN AR NH MA RI CT NJ DE MD DC SC MS but had problems that prevented them from enrolling, and another NY MI IA NE UT VT ME MN AL LA GA FL AK cated or confusing (Latino Decisions, 2015). HI SOURCE: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015a. Choice RAND PE152-4 Functioning markets for individual coverage have developed in all states, and at least two insurers offer individual policies on the exchanges voluntarily is also real given the small size of some exchanges of every state. However, the number of insurers that markets: Only about 12,000 and 18,000 individual policies were offer exchange policies remains limited in the less populous states, bought on Hawaii’s and North Dakota’s exchanges, respectively, as Figure 4 illustrates. More than half of the states have fewer than for 2015 (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015b). four carriers, and West Virginia has only two. Through three changes to the cost–benefit trade-off, privately We have not found evidence that the limited number of facilitated exchanges could attract additional insurers and increase competitors in many states restricts consumer choice in a mean- the number of plan options that they make available. First, ingful fashion. However, it does expose less populous states to the companies would expect that improved consumer experience would risk of having no plans or no competing plans that sell individual policies on their exchanges if only one or two companies decide to attract more shoppers to the exchanges and makes actual purchases leave the market or become insolvent, as was the case with Iowa’s more likely (see earlier discussion) (Wong, 2014a; Latino Decisions, CoOportunity Health. That departure left some consumers with 2015). Second, the opportunity to market additional products, only one company offering plans on the exchange (CoOportunity such as non-QHP plans and supplemental coverage, could entice Health, 2015; Masters, 2015). This risk of companies leaving the insurers to participate in the exchanges, although insurers can 12 already market those products through existing channels, such law’s intent to provide greater transparency and simplify decision- as brokers and their own websites. Third, an increase in insurer making. Even if insurer-specific or nonexhaustive websites include participation might follow if privately facilitated exchanges succeed disclaimers about the information provided, some consumers in streamlining and automating plan-management functions—in might feel fatigue from the additional decision (choosing the type particular, the QHP application process. This change would go of exchange website from which to purchase insurance) beyond well beyond the scope of the current web-based entities and would decisions about the QHP to purchase (Rice, 2013). Decision require collaboration between regulators, insurers, and private fatigue related to website choice could lead consumers to avoid the exchange operators. market and might differentially affect certain types of consumers, such as those with low health or financial literacy. Consumer Protection Further, consumers might not view the privately facilitated The Affordable Care Act increased consumer protection in the exchanges as being the same kind of honest broker as the govern- individual market primarily through two mechanisms. The first ment exchanges. Consumers might—legitimately—fear that filters, was the creation of standardized and comprehensive policies with defaults, and other nudges will direct them toward certain plans strict pricing regulation and guaranteed issue, and the second was that represent profit potential for the exchange provider or associ- the establishment of a unified exchange for subsidy-eligible plans, ated insurers, as opposed to representing the consumer’s optimal on which all available options are listed for comparison. choice. McWilliams points out that nudging is a form of agency A shift to privately facilitated exchanges would not affect and notes that the agent’s interests might not necessarily align with the first mechanism because regulations for individual market the consumer’s interests (McWilliams, 2013). Privately facilitated policies would still apply. However, competing exchanges might create confusion and uncertainty among consumers, in particular exchanges could also raise consumer concerns about data protec- if exchanges may market QHPs along with non-QHP and other tion and privacy. Measures to mitigate concerns about consumer protection products, and offer only a subset of the available plans or plans of a include the following: single insurer. • maintenance of at least one exchange that lists all QHPs in a Although it might be positive for competition and innovation, differentiation, if it confuses consumers, would undermine the given market Although it might be positive for competition and innovation, differentiation, if it confuses consumers, would undermine the law’s intent to provide greater transparency and simplify decisionmaking. 13 The existence of both short- and long-term revenue potential is essential if the government wishes to allow the private sector to fully provide the selected exchange functions Affordable Care Act, who provide unbiased advice on coverage • regulation to govern exchange transparency so that consumers know what range of plans is listed and which plans meet QHP options and support in completing the enrollment process. criteria • regulation to ensure that decision-support tools do not direct Cost and Sustainability consumers to plans for profiteering purposes (e.g., kickbacks The federal government launched HealthCare.gov with substantial from certain insurers to exchanges for directing healthy investment of federal funds and staff resources. Although many people to its plans or from insurers to exchanges in response experts have criticized the high development costs, those initial to prioritized direction to the insurer’s plans). State insurance costs are sunk and should not influence decisions about the regulations address steerage by brokers, but the federal govern- future exchange model. Instead, the appropriate comparison is ment would need to develop new regulatory guidance on the between the costs to state and federal governments of directly sale of insurance in this setting. providing front-end exchange services on the one hand and, on • strict regulation of data privacy and security to give consumers the same level of protection that they currently enjoy when the other hand, monitoring the privately facilitated exchanges. The enrolling through the federal or a state exchange monitoring costs are probably considerably lower than the current • enforcement of those rules with a cadre of skilled workers who operating budgets, and the potential savings thus could be substan- can effectively monitor the exchanges and help avoid regula- tial. For example, the federal contract to Accenture to support tory capture (wherein regulators act in the interest of private- HealthCare.gov for the next five years is worth $563 million sector entities that dominate the industry they are regulating (although not all of those costs are strictly associated with front-end instead of in the public interest) (Dal Bó, 2006). services) (Accenture, 2014; Johnsrud, 2014). Looking ahead, we see that resources available for maintaining and improving the Although effective monitoring and regulatory oversight could exchanges could be more limited, making more urgent the need to help alleviate these concerns in substance, private exchange websites would need to earn consumers’ trust for potential gains in enroll- consider alternatives for increasing the affordability and sustain- ment to be realized, and approaches to monitoring and regulation ability of the exchanges. Although states relied on federal grants would need to be adapted to this context. Moreover, consumers to develop their exchanges, the law requires that state exchanges would still need to have free access to navigators, as defined by the be self-sustaining by 2015. Meanwhile, a change in administration 14 from the presidential election could change funding priorities to support exchanges. These challenges include concerns about (Dash, Lucia, et al., 2013; Dash, Giovannelli, et al., 2014). the consumer experience, costs of sustaining the exchanges, and 5 uncertainty around the availability of resources for continuing The existence of both short- and long-term revenue potential is essential if the government wishes to allow the private sector operations, and the existence of a sizable untapped market of to fully provide the selected exchange functions. The emergence consumers who are eligible for but not enrolled in exchange plans, of web-based entities in the context of health insurance and their including young adults. In this perspective, we discuss a model wherein the government longevity in other domains suggests that privately facilitated retains control over core sovereign functions (regulation of insurers, exchanges can be financially sustainable. Like travel websites, eligibility determinations, and transfer of subsidy payments to those exchanges could generate revenues from broker commis- insurers) but allows the private sector to assume responsibility for sions, advertising, and listing fees for products other than QHPs. more-peripheral exchange functions, such as development and In the short term, the continued existence of state and federal sustainment of the technical architecture for exchange websites and exchanges while the privately facilitated exchange market incubates the software overlays that support plan comparison and enrollment. protects against instability in the market. Because the Affordable Our analysis suggests that this shift could yield benefits Care Act requires the existence of an exchange in each state, the in terms of improved consumer experience and, consequently, health insurance industry might have to commit to maintain a increased enrollment and lower costs for state and federal govern- consortium-funded exchange if no privately facilitated exchange ments, although the shift would have to be gradual and closely appears sustainable in a given state. monitored to ensure that viable, attractive, and trusted alternatives to the public exchanges emerge for all states. The main risks are Summary reduced consumer protection, increased consumer confusion, The Affordable Care Act overhauled the individual health insur- and the lack of a viable revenue base for privately facilitated ance market to help bring health coverage to the vast majority exchanges—in particular, in less populous states. Overall, we of Americans. A well-functioning and sustainable marketplace is believe that the benefits are large enough and the risks sufficiently integral to achieving the law’s objective of reducing the number manageable to seriously consider such a shift. We should qualify, of uninsured. Several challenges the exchanges face suggest however, that we intend for this perspective to stimulate the policy consideration of alternative models of public–private partnerships debate, and it does not offer a formal and conclusive assessment of costs and benefits. Efforts to monitor and rigorously evaluate Some states will use portions of existing premium taxes to help fund their exchanges; others could levy taxes on insurers in the individual and small-group markets; and some plan to use advertising revenue on exchange websites. 5 privately facilitated exchanges already in operation will be important for informing the policy discussion going forward. 15 References Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, “Essential Health Benefits Standards: Ensuring Quality, Affordable Coverage,” undated. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/ehb-2-20-2013. html “3%,” HealthSherpa, February 11, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://blog.healthsherpa.com/3-percent Accenture, “Accenture Awarded Five-Year Contract to Continue Successful HealthCare.gov Work,” press release, December 29, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://newsroom.accenture.com/news/ accenture-awarded-five-year-contract-to-continue-successful-healthcare-gov-work. htm ———, “Health Insurance Marketplace Guidance: Role of Agents, Brokers, and Web-Brokers in Health Insurance Marketplaces,” Washington, D.C.: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, updated November 7, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/ Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/Downloads/ May_1_2013_CCIIO_AB_-Guidance_110414_508.pdf Andrews, Michelle, “In Addition to Premium Credits, Health Law Offers Some Consumers Help Paying Deductibles and Co-Pays,” Kaiser Health News, July 9, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://khn.org/news/070913-michelle-andrews-on-cost-sharing-subsidies/ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid and CHIP: December 2014 Monthly Applications, Eligibility Determinations and Enrollment Report, Baltimore, Md., February 23, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/program-information/ downloads/december-2014-enrollment-report.pdf Arnold, Laurel, Jamie Brennan, Kristan Drzewiecki, Stuart Venzke, and Dave Walsh, White Paper: HIX Consumer Experience, Private Sector Technology Group, August 19, 2012. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.pstg.org/newsletters/hix_consumer_experience_white_paper.pdf Baker, Tom, Adrienne Beatty, Gabbie Nirenburg, and Janet Weiner, “Window Shopping on Healthcare.gov and the State-Based Marketplaces: More Consumer Support Is Needed,” Philadelphia, Pa.: Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, December 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://ldi.upenn.edu/uploads/media_items/ window-shopping-on-healthcare-gov-final.original.pdf Constine, Josh, “Pinterest Hits 10 Million U.S. Monthly Uniques Faster Than Any Standalone Site Ever—comScore,” Tech Crunch, February 7, 2012. As of June 5, 2015: http://techcrunch.com/2012/02/07/pinterest-monthly-uniques/ CoOportunity Health, “Notice of Liquidation for CoOportunity Health,” February 28, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.cooportunityhealth.com/ Barkakati, Nabajyoti, and Gregory C. Wilshusen, Healthcare.gov: Actions Needed to Address Weaknesses in Information Security and Privacy Controls, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO-14-730, September 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-730 Dal Bó, Ernesto, “Regulatory Capture: A Review,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 22, No. 2, Summer 2006, pp. 203–225. Dash, Sarah J., Justin Giovannelli, Kevin Lucia, and Sean Miskell, “State Marketplace Approaches to Financing and Sustainability,” Commonwealth Fund, November 6, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2014/nov/ state-marketplace-approaches-to-financing-and-sustainability Bidgood, Jess, “More Than One Way to Buy a Plan,” New York Times, March 6, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.nytimes.com/news/affordable-care-act/2014/03/06/ more-than-one-way-to-buy-a-plan/ Dash, Sarah J., Kevin Lucia, Katie Keith, and Christine Monahan, “Implementing the Affordable Care Act: Key Design Decisions for State-Based Exchanges,” Commonwealth Fund, July 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2013/jul/ design-decisions-for-exchanges Brownlee, John, “4 Things HealthCare.Gov 2.0 Gets Right (and 5 Things It Still Gets Wrong),” Fast Company, November 17, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.fastcodesign.com/3038669/ 4-things-healthcaregov-20-get-right-and-5-things-it-still-gets-wrong 16 Dash, Sarah J., Christine Monahan, and Kevin Lucia, “Health Policy Brief: Health Insurance Exchanges and State Decisions,” Health Affairs, July 18, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_96.pdf ———, “Marketplace Enrollment as a Share of the Potential Marketplace Population,” March 31, 2015b. As of June 5, 2015: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/ marketplace-enrollment-as-a-share-of-the-potential-marketplace-population-2015/ Dicken, John E., Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Status of CMS Efforts to Establish Federally Facilitated Health Insurance Exchanges, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO-13-601, June 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-601 Johnsrud, Sue, 2014–15 Covered California Budget, Covered California, c. 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://hbex.coveredca.com/financial-reports/PDFs/2014Budget.pdf DiJulio, Bianca, Jamie Firth, Larry Levitt, Gary Claxton, Rachel Garfield, and Mollyann Brodie, “Where Are California’s Uninsured Now? Wave 2 of the Kaiser Family Foundation California Longitudinal Panel Survey,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, July 30, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://kff.org/health-reform/report/where-are-californias-uninsured-now-wave-2of-the-kaiser-family-foundation-california-longitudinal-panel-survey/ Krughoff, Robert, Walton Francis, and Robert Ellis, “Helping Consumers Choose Health Plans in Exchanges: Best Practice Recommendations,” Health Affairs Blog, February 29, 2012. As of June 5, 2015: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2012/02/29/helping-consumers-choose-health-plansin-exchanges-best-practice-recommendations/ King v. Burwell, 576 U.S. ___, June 25, 2015. As of June 29, 2015: http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-114_qol1.pdf Kuranda, Sarah, “HealthCare.Gov v2.0: Software Developers Create Site to Trump Obamacare Site Woes,” CRN, November 18, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.crn.com/news/channel-programs/240164064/healthcare-gov-v2-0software-developers-create-site-to-trump-obamacare-site-woes.htm Doulgerof, Ivana, “Usability Glossary,” in How to Improve the Usability of Our Websites: Main Findings and Conclusions from the Seminar Organised by the Management Organisation Unit, Greece, briefing to the Inform network of the European Commission, Brussels, November 27, 2008. As of June 23, 2015: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/country/commu/ docevent/26112008/5_doulgerof_glossary.pdf Latino Decisions, Topline Results: Latino National Health Survey, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico, March 24, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.latinodecisions.com/files/1214/2707/3700/ UNM_RWJF_Center_Toplines_Posted.pdf Fernandez, Bernadette, and Annie L. Mach, Health Insurance Exchanges Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, R42663, January 31, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42663.pdf Levy, Jenna, “In U.S., Uninsured Rate Holds at 13.4%,” Gallup, October 8, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.gallup.com/poll/178100/uninsured-rate-holds.aspx Fung, Brian, “Signing Up for Obamacare Could Someday Take as Little as 10 Minutes,” Washington Post, February 26, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-switch/wp/2014/02/26/ signing-up-for-obamacare-could-someday-take-as-little-as-10-minutes/ Madnick, Stuart, Michael Siegel, Mary Alice Frontini, Saraubh Khemka, Steven Chan, and Howard Pan, Surviving and Thriving in the New World of Web Aggregators, unpublished paper presented at the Society for Information Management Workshop, Brisbane, Australia, December 2000. “HealthCare.gov’s Tech Improvements Mean You Can Now Window Shop,” All Tech Considered, November 10, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=363052856 Masters, Clay, “Health Insurance Startup Collapses in Iowa,” National Public Radio, January 14, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/01/14/376792564/ health-insurance-startup-collapses-in-iowa Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, “Number of Issuers Participating in the Individual Health Insurance Marketplaces,” c. 2015a. As of June 5, 2015: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/ number-of-issuers-participating-in-the-individual-health-insurance-marketplace/ McWilliams, J. Michael, “Information Transparency for Health Care Consumers: Clear, but Effective?” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 28, No. 11, November 2013, pp. 1387–1388. 17 “Meet the Press Transcript: November 16, 2014,” NBC News, November 16, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.nbcnews.com/meet-the-press/ meet-press-transcript-november-16-2014-n249601 Public Law 111-148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, March 23, 2010. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/PLAW-111publ148/PLAW-111publ148/ content-detail.html Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “How Many Individuals Might Have Marketplace Coverage After the 2015 Open Enrollment Period?” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, issue brief, November 10, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2014/Targets/ib_Targets.pdf Rice, Thomas, “The Behavioral Economics of Health and Health Care,” Annual Review of Public Health, Vol. 34, 2013, pp. 431–447. Skopec, Laura, and Richard Kronick, Market Competition Works: Proposed Silver Premiums in the 2014 Individual Market Are Substantially Lower Than Expected, Washington, D.C.: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, updated August 9, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2013/MarketCompetitionPremiums/ ib_premiums_update.cfm ———, Health Plan Choice and Premiums in the 2015 Health Insurance Marketplace, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, updated January 8, 2015a. As of June 5, 2015: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2015/premiumreport/healthpremium2015.pdf Sprung, Andrew, “How to Reboot Healthcare.gov,” New Republic, September 17, 2014. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.newrepublic.com/article/119474/ government-can-revive-obamacare-site-healthcaregov ———, Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 10, 2015b. As of June 5, 2015: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2015/MarketPlaceEnrollment/Mar2015/ ib_2015mar_enrollment.pdf Venkatesh, Viswanath, Hartmut Hoehle, and Ruba Aljafari, “A Usability Evaluation of the Obamacare Website,” Government Information Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4, October 2014, pp. 669–680. Ornstein, Charles, “Please Wait”: New-and-Improved HealthCare.gov Has Same Old Problems, ProPublica, December 2, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.propublica.org/article/ new-and-improved-healthcare-dot-gov-has-same-old-problems Wlodarz, Derrick, “Healthcare.gov: How Washington’s IT Project Leviathan Failed Us, and Here’s How We Fix a Broken System,” BetaNews, May 5, 2014 Pacific Business Group on Health, “Top 5 Rules for Decision Support, and Strategies to Bridge the Gaps,” issue brief, 2013. As of June 5, 2015: http://www.pbgh.org/storage/documents/ PBGH_PlanChoiceBrief_Top5Rules_022113.pdf Wong, Charlene A., David A. Asch, Cjloe M. Vinoya, Carol A. Ford, Tom Baker, Robert Town, and Raina M. Merchant, “The Experience of Young Adults on HealthCare.gov,” Annals of Internal Medicine, letter, online-first version, July 8, 2014a. As of June 5, 2015: http://ldi.upenn.edu/uploads/media_items/ the-experience-of-young-adults-on-healthcare-gov-suggestions-for-improvement. original.pdf Paradise, Julia, Medicaid Moving Forward, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, March 9, 2015. As of June 5, 2015: http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/medicaid-moving-forward/ ———, “The Experience of Young Adults on HealthCare.gov: Suggestions for Improvement,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 161, No. 3, 2014b, pp. 231–232. 18 Acknowledgments The research underlying this paper was sponsored by Aetna, Inc., and conducted in RAND Health Advisory Services, the consulting practice of RAND Health. The authors would like to thank Justin Giovannelli and Chapin White for their thorough review and instructive feedback. Special thanks also to Patrick Orr for helping us with figures, references, and copyedits. A profile of RAND Health Advisory Services, its capabilities and publications, and ordering information can be found at www.rand.org/rhas. About the Authors Carole Roan Gresenz is a senior economist and director of the Economics, Sociology, and Statistics research department. She holds a Ph.D. in economics from Brown University and a B.A. in economics from Loyola University Maryland. Emily Hoch is manager of RAND Health Advisory Services, the consulting practice of RAND Health. She received her M.Sc. from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and B.A. from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Christine Eibner is a senior economist at RAND. She earned her bachelor’s degree in English and economics from the College of William and Mary and her doctorate in economics from the University of Maryland, College Park. Robert S. Rudin is an information scientist at RAND. He holds a Ph.D. in technology, management, and policy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Soeren Mattke is a senior scientist and the managing director of RAND Health Advisory Services, RAND Health’s consulting practice. He received his M.D. from the University of Munich and his M.P.H. and D.Sc. from the Harvard School of Public Health. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. R® is a registered trademark. For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/PE152. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation C O R P O R AT I O N www.rand.org PE-152 (2015)