An Economic Analysis of Georgia’s Black Belt Counties

advertisement

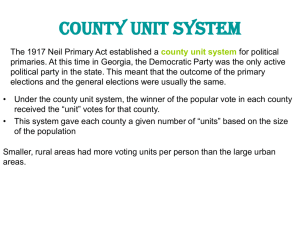

An Economic Analysis of Georgia’s Black Belt Counties Brigid Doherty1 and John McKissick2 1 Economist and 2 Coordinator, Professor, and Extension Specialist CR-02-06 Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences The University of Georgia April 11, 2002 Introduction As with many states, Georgia has historically had areas of high poverty among its counties. In Georgia, and in the Southeast, counties with high poverty levels have been labeled “black belt” counties. This paper dissects the economies of black belt counties and compares them with non-black belt counties. The main thesis of this paper is to determine the ability of black belt counties to be economically competitive. Data For purposes of this paper, the black belt counties are as defined by The Black Belt Data Book (Wimberley, Morris and Woolley). The Black Belt Data Book lists counties by percentage of total population in poverty. Georgia counties with a percent of total population in poverty of over twenty percent were included in this analysis. The counties included are shown in red in the following map. Map 1: Georgia Black Belt Counties Catoosa Dade Walke r Fan nin Wh itfiel d Murray Gordon Chattoo ga Floyd Union Cherokee Forsyth Haralso n Rabun Jack so n Barrow Gwi nnett Cobb Pauldi ng Town s Wh ite Habersham Lum pk in Steph ens Dawso n Banks Frankli n Hall Pickens Barto w Polk Gilm er Classification Belt Counties Non-Belt Counties Hart Elbe rt Madi son Clarke Ogleth orpe Ocone e Wilkes Walto n De Kalb Rockdale Morgan Ne wton Clayton Greene Taliaferro Fulton Do uglas Carroll Coweta Heard Meriwether Tro up Pike Jaspe r Butts Spalding Lamar Monroe Putnam Hancock Baldw in Jone s Colum bia Warren McDuffie Hen ry Faye tte Lin col n Richmo nd Glascock Burk e Washin gton Jeffe rson Upso n Bibb Harris Talbot Crawfo rd Taylor Muscogee Do oly Terrell Lee Clay Cal houn Do ugherty Irw in Wo rth Jeff Davis Coffee Tift Mille r Mitchel l Colquitt Berrien Bulloch Evans Effi ngham Bryan Chatham Tattnall Early Baker Can dler Telfair Ben Hill Turn er Tre utlen Montgo mery Wh eeler Toom bs Do dge Wilcox Crisp Randolph Laurens Bleckley Pulaski Sum ter Quitman Scre ven Em an uel Hou ston We bster Jenk ins John son Peach Maco n Mario n Chattahoo ch ee Schle y Stewart Wilkinson Twiggs Atk inson Lon g Wayne Bacon McInto sh Pierce Ware Cook Liberty Appling Brantley Glyn n Lanie r Se minol e De catur Clinch Grady Thom as Bro oks Charlton Cam den Low ndes Echols 1 Methods Many methods exist for examining the structure and competitiveness of regions and counties. Two such methods will be implemented in this paper. The first method breaks the local economy into sectors. This can be done by sales and by employment. This method also addresses the issue of productivity, manufacturing mix, and agriculture. The second method examines receipts to households by their sources. Input-output models allow for both analyses to occur. The input-output model software called IMPLAN (IMpact Analysis for PLANning) was used for this report. Input-output models are designed to illustrate the flow of money throughout the economy. These models show the market value of goods and services exchanged by industries to produce a final good. IMPLAN expands on input-output modeling by including the Social Accounting Matrix (SAM). The SAM builds dimension into the model on two levels. First, the SAM includes the market value between both industrial and non-industrial groups (households, government, investment and trade). Second, the SAM includes non-market valued exchanges, such as those between government and households. Several IMPLAN models were developed using 1999 data, the most current available. Each black belt county was modeled to allow analysis of individual economies. The black belt counties were also modeled as a group to allow for ease of comparisons. Finally, the non-belt counties were modeled as a group. Sector Analysis As mentioned above, IMPLAN has a basic input-output structure as its main component. This input-output structure traces flows of dollars among industries. The industrial classification used in IMPLAN follows the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) scheme. Thus, industries can be grouped together into sectors. Each sector contains a multitude of closely related industries. IMPLAN has ten major sectors; agriculture, mining, construction, manufacturing, TCPU (transportation, communications and utilities), trade, FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate), services, government and other. The agricultural sector contains all production agriculture, forestry and services related to agriculture and forestry. It does not include manufacturing related to agriculture, such as milk processing. Many manufacturing activities rely on agricultural production in order to exist in the state. The mining sector includes all activities related to mining. Construction includes the building of new structures, but does not include all maintenance and repair activities. Some maintenance and repair is included in services. Manufacturing contains all activities related to manufacturing and has the most industries in the IMPLAN model. TCPU stands for transportation, communication and utilities. This includes items like telephone companies, utility companies and railroads. The trade sector is comprised of wholesale and retail trade, which includes restaurants and grocery stores. FIRE represents finance, insurance and real estate. Services are all items that are typically considered service oriented, such as hotels, car repairs and health services. The government sector includes 2 both federal and state/local government. Finally, the other category exists to help balance the model with inventory adjustments and other items. IMPLAN can categorize both output and employment data by these sectors for each economy. Thus, this paper will examine how output and employment differ in the two groups of counties. This paper will then add employment compensation data to examine productivity and wages. Output The first measure considered is output, which is the value of all goods and services produced in the area of analysis. Total output for the black belt counties is $52.7 million dollars. This translates into a per capita value of approximately $41,000. Per square mile, this is equivalent to $1.8 million. Total output for the non-belt counties is $417.2 million. This translates into a per capita value of $62,000. Output per square mile equals $14.2 million. Chart 1: Output per Capita and per Square Mile, Georgia 1999 $70,000 $60,000 $50,000 $40,000 $30,000 $20,000 $10,000 $0 Belt Non Belt Output Per Capita Output per Square Mile (thousands) Chart 2 shows the percentage value of output from each sector in the black belt economies. Manufacturing provides the largest percentage of output in the counties, followed by services and trade. Chart 2: Black Belt Output Government 9.6% Services 12.7% FIRE 8.4% Trade 10.8% TCPU 6.9% Other Agriculture 0.1% 6.0% Mining 1.7% Construction 7.1% Manufacturing 36.8% 3 Chart 3 illustrates the same information as chart 2, but for the non-black belt counties. Manufacturing is the largest contributor to the economy, followed by services and trade. Chart 3: Non Belt Output Agriculture Mining 1.0% 0.1%Construction 7.8% Government 7.4% Services Manufacturing 18.1% 24.4% Other 0.1% FIRE 13.8% Trade 15.2% TCPU 12.1% Several interesting conclusions can be drawn from a comparison of the data and the two pie charts. First, both groups of counties have manufacturing, services and trade as their three biggest economic sectors in terms of output. However, the shares of the economy held by these sectors are different. In black belt counties, manufacturing accounts for a larger share of total output than in the non-belt counties. Second, manufacturing and agriculture show dramatic differences in share of total output. Next, on both a per capita and per square mile basis, the black belt counties are significantly lower in terms of output. Fourth, the economy of the non-belt counties is more diversified with a service orientation. Employment The second measure used is employment. Total employment in the black belt counties is 664,066. This means that roughly fifty-two percent of the total population is employed in the region. There are 23 employees per square mile. Chart 4 shows employment by sector in the black belt counties. It is immediately clear that although manufacturing contributes 37% of total output, it only employs 17.8% of the workers in the counties. Trade and services are tied as the largest sectors of employment in the belt counties. 4 Chart 4: Black Belt Employment Agriculture 7.0% Government 18.8% Other 1.4% Mining 0.7% Construction 5.6% Manufacturing 17.8% Services 20.4% FIRE 4.2% TCPU 3.7% Trade 20.3% Employment in the non-belt counties is 4.2 million people. Thus, sixty-two percent of the total population is employed in the non-belt counties. There are 142 employed persons per square mile. Employment by sector in the non-belt counties is the focus of chart 5. The trend of manufacturing having a lower percentage of employment than output is true in these counties too. Service becomes the largest sector of employment, followed by trade. Chart 5: Non Belt Employment Agriculture 1.5% Government 14.3% Other 0.7% Mining 0.1% Construction Manufacturing 7.2% 11.8% TCPU 5.9% Services 29.2% FIRE 6.9% Trade 22.4% 5 A comparison of the two employment pie charts reveals several items. Both groups of counties have lower percentages of workers in manufacturing than they do output in that sector. This suggests that manufacturing is more productive per worker than other sectors. Services and trade become major employers in both groups of counties. Government also becomes a larger portion of the pie in the employment graphs. These observations raise many issues surrounding output and employment in both sets of counties. A major question is the role of manufacturing in the economy. Clearly, employees in manufacturing sectors are more productive than other sectors if they can produce more output with fewer employees. This observation raises speculation regarding output per worker across sectors and across groups of counties. Another major issue is the composition of manufacturing. A comparison of the types of industries in each county group may reveal differences in the competitive nature of the groups. Finally, the role of agriculture is in question. The next sections of this paper will attempt to answer these areas of speculation. Output per Worker Chart 6 graphs output per worker in each of the sectors in both the belt and nonbelt counties. Total output per worker in the black belt counties is $79,000, while output per worker in the non-belt counties is $100,000. Output per worker is essentially equal in agriculture. The belt counties are more productive than the non-belt counties in mining. However, in every other sector, the non-belt counties have higher output per worker. Chart 6: Output per Worker by Sector, Georgia 1999 250,000 150,000 Belt Non Belt 100,000 50,000 ric ul tu re C Min on in M stru g an c uf t i o n ac tu rin g TC PU Tr ad e FI R Se E G rvi ov ce s er nm en t O th er - Ag Dollars 200,000 6 Output per worker can be considered as one measure of productivity. Productivity in turn, can be viewed as a measure of competitiveness. Higher productivity usually indicates a more efficient use of the factors of production; land, labor and capital. Manufacturing Mix Earlier analysis in this paper shows that manufacturing is a larger component of the black belt’s total output, but that output per worker is lower in the belt counties than the non-belt counties. Thus, it is logical to wonder about the composition of the manufacturing industry in both the belt and non-belt counties. Chart 7 shows the mix of industries in the manufacturing sector for the black belt counties. In this chart, the industries are grouped at the 2-digit SIC level. This allows for more detailed analysis of the types of manufacturing companies in the black belt counties. Chart 7: Manufacturing Mix, Black Belt Counties, Georgia 1999 Scientific Transportation instruments Food Processing equipment 1% 18% Miscellaneous 7% 0% Tobacco Electrical equipment Industrial machinery Manufacturing 4% 9% 0% Fabricated metals Textiles 6% 9% Primary metals Apparel 2% 7% Stone, glass, clay 2% Furniture Leather Products Chemicals 1% 0% 4% Wood Products Printing/Publishing 15% Rubber Products 2% Pulp and paper 4% Petroleum Products 9% 0% According to the chart, food processing and wood products are the two biggest manufacturing industries in terms of output for the black belt counties. 7 Chart 8 illustrates the mix of manufacturing industries by output in the non-black belt counties. In these counties, food processing and transportation equipment produce the largest shares of total output. Chart 8: Manufacturing Mix, Non-Black Belt Counties, Georgia 1999 Transportation equipment 14% Scientific instruments Food Processing 1% Miscellaneous 15% 1% Electrical equipment 6% Industrial machinery 6% Fabricated metals 3% Primary metals 3% Stone, glass, clay 3% Leather Products 0% Rubber Products 4% Tobacco Manufacturing 5% Textiles 14% Apparel 2% Chemicals Furniture 7% 1% Printing/Publishing 5% Pulp and paper Petroleum Products 7% 0% Wood Products 4% Agriculture The percent contributed by agriculture to total output changed fairly dramatically from the black belt counties to the non-belt counties. Since many of the counties classified in the black belt are rural, South Georgia counties, it is not surprising that agriculture plays a larger role in the economy of these counties. However, it is not clear what role agriculture plays in contributing to competitiveness. Output per worker was used earlier as a measure of productivity because it alludes to the effectiveness of the use of land, labor and capital. Of these factors of production, only land is not mobile. In other words, labor and capital can be adjusted by policy decisions and other activities. Land cannot. Thus, it would be remiss not to explore the value of agricultural production from the black belt counties versus non-belt counties. 8 Map 2: Farm Gate Value Per Acre, Georgia 2000 Farm Gate Value Per Acre 0 - 500 500 - 900 900 - 1700 1700 - 3000 3000 - 7000 Map 2 shows farm gate value per acre in each county in Georgia. Counties classified as black belt tend to be the same counties with low farm gate value per acre. Conversely, counties with high farm gate value per acre are mainly those not in the belt. Counties with high values per acre tend to those with high value per acre commodities, such as poultry and vegetable production. Charts 9 and 10 display the break down of farm gate income by major category. The belt counties have higher concentrations of crops and forestry, which are typically low value per acre enterprises. Chart 9: Farm Gate Value by Category, Belt Counties 2000 Vegetables 9% Other 11% Animals 28% Forestry 11% Crops 41% 9 Chart 10: Farm Gate Value by Category, Non-Belt Counties 2000 Vegetables 7% Forestry 8% Crops 21% Other 4% Animals 60% Compensation per Worker This paper has explored sources of output and employment. It has considered productivity issues and looked at the mix of manufacturing companies and the role of agriculture. However, the sector analysis is not complete without a discussion of compensation per worker. Compensation per worker by sector is shown in chart 11. Total compensation per worker in the belt counties is $24,000. Compensation per worker in non-belt counties is $33,000. Non-belt counties receive higher compensation per worker in every sector except mining. One conclusion is that employees are being compensated for higher output per worker with higher pay. It is important to note that employee compensation here is defined as wages and benefits. Self-employment income is not included in this definition. Thus, lower averages of compensation may be noted in areas such as agriculture. There are more part-time workers, thus lower values per person, in agriculture. This combined with the fact that many agricultural producers claim their income as self-employment income, explains the relatively low value of agricultural compensation per worker. 10 Chart 11: Compensation per Worker Belt Non Belt Ag ric ul tu re M C on inin g st ru M c an uf tion ac tu rin g TC PU Tr ad e FI R Se E G rvic ov es er nm en t O th er 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 - Household Receipts Having completed sector analysis using basic input-output theory, one can now advance another step by using the Social Accounting Matrix (SAM). To review, the SAM adds dimension to an input-output model by adding flows between industrial and non-industrial sources and by adding non-market values for good and services exchanged. The SAM in IMPLAN essentially has thirteen components to trace dollar flows. These are; industry, commodity, employee compensation, proprietary income, other property income, indirect business taxes, households, federal government, state/local government, enterprises (corporations), capital, inventory, and trade. Since the SAM is designed to illustrate the exchange of monetary value throughout the economy, the matrix itself has both rows and columns. The rows show receipts to a sector (say households) from the other sectors. The columns show the expenditures by one sector (say employee compensation) to another (households). While the SAM itself is interesting, for purposes of this paper, the focus will be on the household row. This will reveal the amount of dollars transferred to households from the other sectors. Some interpretation of the sectors will be needed. Wages and benefits (employee compensation) represent dollars provided to households as payment for work. However, compensation for self-employment is part of the proprietary income category. Property income includes monies received at households from the ownership of property, like rents and dividends. Households do not receive indirect business taxes as this sector captures taxes. Receipts to households from households include household 11 payments of interest to other households, such as personal notes, contracts for deed and other inter-household loans. The federal government essentially makes two types of payments to households; interest payments and transfer payments. Interest payments cover dollars returned to holders of government bonds and other securities. Social security, veterans benefits, food stamps, direct relief, earned income credit, and aid to students are among the transfer payments. State and local governments also make interest and transfer payments to households. Interest payments are mainly for bond holders. Transfer payments are mostly comprised of welfare payments and unemployment compensation. Receipts to households from enterprises are entirely from dividend income, or the distribution of corporate profits. Capital represents dis-savings or withdrawals of capital by households to support their consumption. Households have no inventory adjustments. Trade receipts to households include the value of goods and services exchanged across state and federal boundaries. Total Total receipts to black belt households were $32.9 million in 1999. The break down of these receipts by source is shown in chart 12. Wages and benefits provide the largest source of income to households. Enterprises (corporate dividends) provide the second biggest portion of receipts, followed by the federal government. Chart 12: Household Receipts by Source, Black Belt Counties, Georgia 1999 Foreign Trade 0.22% Domestic Trade 0.02% Capital 10.95% Commodity 0.02% Wages /Benefits 39.91% Enterprises 18.03% State/Local Govt 1.92% Fed Govt 13.53% Self Emp Comp 7.25% Rents, Dividends Households 6.36% 1.78% Non-belt households received $205.5 million in receipts. Chart 13 graphs the amount of receipts by source for non-belt counties. Wages and benefits comprise over half of receipts by households. Federal government and capital make up the next two highest categories. 12 Chart 13: Household Receipts by Source, Non Black Belt Counties, Georgia 1999 Enterprises 5.91% State/Local Govt 1.06% Domestic Trade 0.03% Capital 8.70% Foreign Trade 0.19% Commodity 0.01% Fed Govt 9.19% Households 2.00% Wages /Benefits 58.85% Rents, Dividends Self Emp Comp 7.03% 7.04% In comparing the two pie charts on household receipts, two things immediately stand out. First, households in non-belt counties receive a large amount of their income from wages and benefits. Second, households in belt counties receive more of their income from enterprises (corporate profits) than non-belt counties. A comparison of the two reveals more about the use of the factors of production as well. Capital in these graphs represents the amount of capital that must be exchanged for dollars in order for households to maintain consumption. Households in belt counties are receiving a higher percentage of their consumption from capital than non-belt counties. Per Capita While the composition of total household receipts is revealing, it is difficult to do direct comparisons. Total per capita in the black belt counties is $26,000 while total per capita household receipts in non-belt counties is $30,000. Chart 14 shows receipts to households by source on a per capita basis. The same two items that were noticeable in the pie charts also are of note in this chart. 13 Chart 14: Household Receipts by Source, Per Capita, Georgia 1999 $20,000 Belt Counties Non Belt Counties $18,000 $16,000 $14,000 $12,000 $10,000 $8,000 $6,000 $4,000 $2,000 n Tr ad om e es t ic Tr ad e ita l re ig C ap D Fo s ag e W C om m od ity /B en Se ef its lf Em p R C en om ts p ,D iv id en ds H ou se ho ld s Fe d St G at ov e/ t Lo ca lG ov t En te rp ris es $- Per Square Mile Comparisons of household receipts per square mile can also illustrate competitiveness. Total household receipts per square mile in the black belt counties are $1,152,880. Total receipts per square mile in the non-belt counties are $7,207,862. Chart 15 shows these receipts by their source. On a per square mile basis, the non-belt counties consistently have higher value per mile. Chart 15: Household Receipts by Source, Per Square Mile, Georgia 1999 $4,500,000 Belt Counties Non Belt Counties $4,000,000 $3,500,000 $3,000,000 $2,500,000 $2,000,000 $1,500,000 $1,000,000 $500,000 tic Tr ad e Tr ad e om es D C ap ita l Fo re ig n iv id en ds H ou se ho ld s Fe d G St ov at t e/ Lo ca lG ov t En te rp ris es D om p C m p R en ts , /B en ef its Se lf E W ag es C om m od ity $- 14 Conclusions This paper has explored the competitiveness of Georgia’s black belt counties compared to the non-belt counties. Two main approaches were taken to accomplish this project. First, a sector analysis was performed. The analysis identified two main areas in which the groups of counties differ: manufacturing and agriculture. These two areas were further explored. Productivity of the sectors was also considered. It was shown that black belt counties are less efficient in the use of some factors of production. Second, an analysis of household receipts was done. This analysis revealed that households in the black belt counties receive less of their income from wages and benefits and more from enterprises than do non-belt counties. Our analysis leads to several conclusions about characterizing the black belt. First, the belt counties have a lower output of goods and services. Second, the counties are more dependent on low wage manufacturing than non-belt counties. Third, there is a low value per acre of agriculture. Finally, the belt counties are more dependent on government and dividends for household income, while their household income is about $8,000 per person lower than non-belt counties. 15